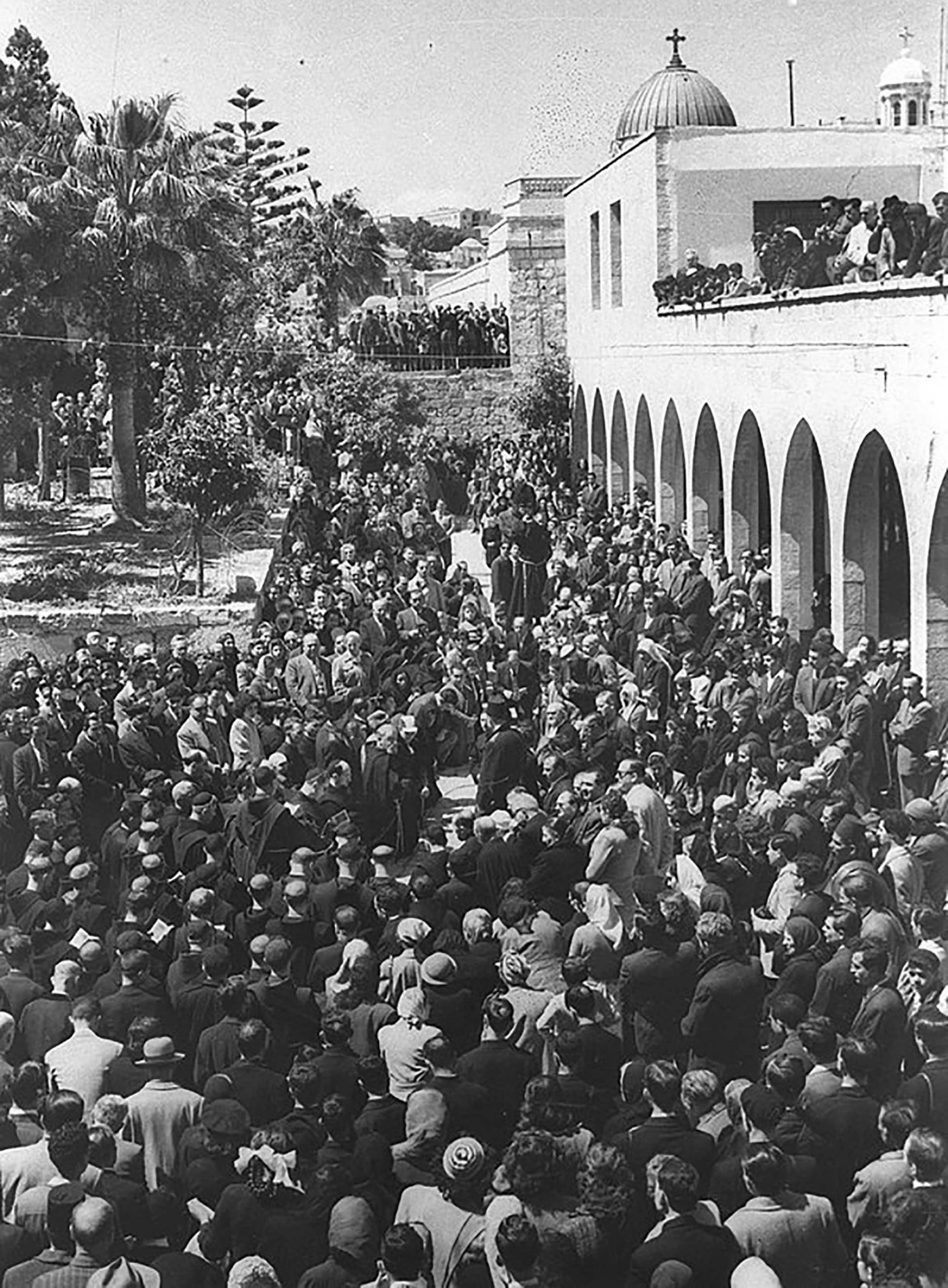

Easter holds a special place in the spiritual calendar of Jerusalem, the city where Jesus Christ is believed to have been crucified, buried, and resurrected. Throughout the Lent season leading up to Easter, Jerusalemites and pilgrims observe various religious ceremonies, including Ash Wednesday, Palm Sunday, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday. A central site to these traditions is the fourth-century Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which was built on the site considered to hold the tomb of Jesus.

Credit:

iStock Photo

Sacred Seasons: Tracing the Holy Calendar of Jerusalem’s Palestinians

Snapshot

This year, Muslims and Christians around the world find their religious calendars intertwined as Ramadan and Lent coincide, marking a period of shared spiritual devotion. In Jerusalem, a sacred land for all three Abrahamic religions, these weeks are particularly eventful, as rites and ceremonies take over the city. Here we highlight some major events and their sites, past and present.

Within the ancient walls of Jerusalem’s Old City also lies Via Dolorosa, Latin for “Way of Suffering,” the route believed to trace Jesus Christ’s path to his crucifixion. Pilgrims flock to Jerusalem to walk in the footsteps of Jesus along Via Dolorosa, which comprises 14 stations, beginning at the Franciscan Chapel of the Condemnation and ending at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

With Jerusalem being home to at least 13 various Christian denominations, the religious landscape is characterized by rich diversity, particularly evident during the celebration of Easter, which is observed on different days due to variations in the liturgical calendars of Christian Orthodox, Catholic, and Protestant traditions.

Three patriarchs reside in Jerusalem, including Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Armenian. Additionally, there are ten other archbishops and bishops; five are Catholic, including Melkite, Maronite, Syrian, Armenian, and Chaldean; three are Orthodox, including Coptic, Syrian, and Ethiopian; and two are Protestant, which are Anglican and Lutheran.1

While Christian pilgrimage to Jerusalem has been an age-old phenomenon, Israeli restrictions and policies that began with the occupation of East Jerusalem in 1967 and exacerbated following the 2023–24 Gaza war have impeded access to the Old City for Palestinians from the occupied territories and Arabs from neighboring countries. During Easter ceremonies, Israeli police block all entrances to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and limit the presence of worshippers to a certain number in the church, denying faithful Christians the right to pray unless they obtain permits, which are not granted to everyone.

It is also worth mentioning that the Easter period historically coincides with another pilgrimage tradition that was traditionally celebrated by Muslims in Palestine, known as the Nabi Musa festival.

Dating back to the Crusader period, the weeklong festival was built around a collective pilgrimage from Jerusalem to a holy site near Jericho, Palestine, where Muslims believe is the location of prophet Moses’ tomb. The procession would usually be headed by the Mufti of Jerusalem and feature men on horseback along with flags, banners, and musical instruments. In recent years, the celebration of the festival has waned, influenced by a combination of political and social factors. Changing demographics and the occupation’s restrictions on movement and access to religious sites have hindered participation, while shifting cultural priorities have diverted attention away from several traditional celebrations observed across historical Palestine since the Ayyubid period, such as the festivals of Nabi Salah and Nabi Rubin.2

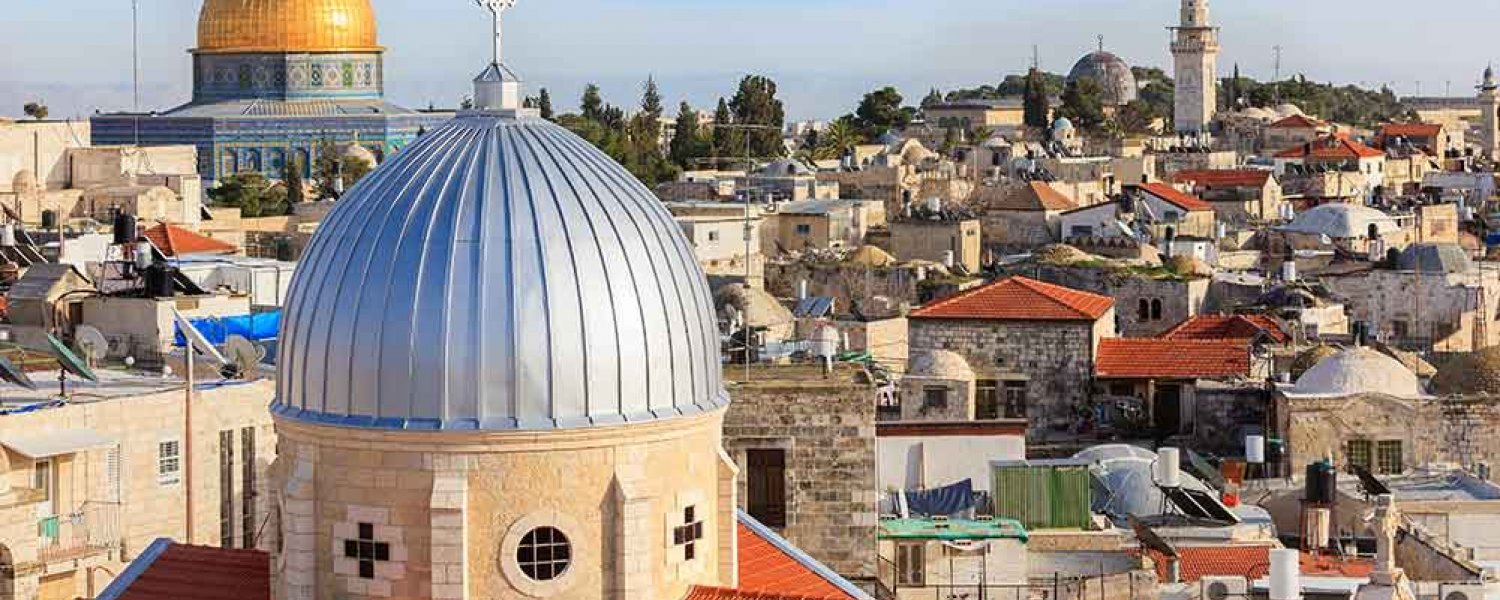

Moreover, Jerusalem holds great significance for Muslims especially during Ramadan, as it is the site of the third holiest mosque, according to Islamic tradition. The city derives its religious prominence from being the first qibla, which is the direction Muslims face when they pray, in Islam, and its association with the Prophet Muhammad’s miraculous nocturnal journey to the city before his ascension to heaven, known as al-lsra’ wa-l-Mi‘raj.

Further, the Dome of the Rock shrine in Jerusalem is believed to be the spot where the Prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven, just as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is believed to be the site of Jesus’ ascension. At the end of the seventh century, the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa Mosque were built on the site of the Prophet Muhammad’s prostrations and ascension. The two mosques and their surroundings became known as al-Haram al-Sharif.

Friday prayer at al-Aqsa Mosque is especially important to Muslims during Ramadan and on Eid al-Fitr, the day when Muslims break their month-long fast. Other observances during Ramadan include the daily evening prayer, known in Arabic as tarawih, and the commemoration of Laylat al-Qadr, one of the holiest nights in Islam, which means “the night of power” in Arabic.

Muslims also visit al-Aqsa Mosque on the morning of Eid al-Adha, the second of the two main holidays celebrated in Islam, which commemorates the willingness of Abraham to sacrifice his son Ishmael in obedience to God’s command.

Prior to Ramadan this year, anticipation swirled around Jerusalem amid speculations about Israeli authority bans and restrictions on entry to al-Aqsa Mosque, particularly following tightened regulations following Israel’s assault on Gaza. Despite allowing worshippers to access al-Aqsa Mosque with permits, Israeli authorities enforced time and age restrictions during Friday prayers.

The journey from the regions outside the municipal boundaries to access the city, the Old City, and al-Aqsa Mosque, which is already challenging due to military checkpoints, has become even more exhausting and uncertain.

For Palestinian Christians and Muslims, however, these political barriers infuse the spiritual journey with sentiments of resistance, steadfastness, and patriotism. Visiting al-Aqsa Mosque for a Palestinian Muslim becomes an emotional journey and an act of patriotism, while for a Palestinian Christian, presence in Jerusalem during Easter signifies not only religious devotion but also a commitment to the city and its social fabric.

Notes

“The Christian Denominations in the Holy Land,” Koinonia, accessed April 29, 2024.

Wadi‘ ‘Awawda, “The Shrine of the Prophet Moses Is an Archaeological Urban Lighthouse on the Edge of the Palestinian Desert” [in Arabic], Al-Quds Al-Arabi, January 16, 2021.