Introduction

Credit:

Dan Porges, Getty Images

Remembering the 1967 Naksa

Snapshot

A conversation among five Palestinian Jerusalemites who recall their memories of the watershed 1967 Naksa and explore some of its impacts on their community and their city.

The following is the text of a Jerusalem Story Roundtable discussion that took place June 5, 2024, on the 57th anniversary of the occupation of East Jerusalem by Israel. Participants shared their memories of the 1967 Naksa (Setback) and reflected on their city—past, present, and future.

Participants were all Palestinian Jerusalemites:

Ziad Abu Zayyad: Lawyer, former minister of Jerusalem Affairs in the Palestinian Authority (PA), former Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC) member, political analyst, and journalist

Khalil Assali: Editor-in-chief of Akhbar elBalad Network and publisher, former chairman of the Jerusalem Journalists’ Club and director of the Media Unit in the President’s Office at al-Quds University, current member of the Waqf Islamic Endowment Council in Jerusalem

Maurine Kouba: Acting director, Yabous Cultural Centre, East Jerusalem

Ahmed Safadi: Director, Elia Foundation for Youth Media, political and economic researcher and analyst

The discussion was organized and moderated on Zoom by journalist Daoud Kuttab for Jerusalem Story.

Participants’ remarks express their own views and not necessarily those of the organizations with which they are affiliated.

Roundtable

Daoud Kuttab: Ziad, you lived through the Naksa more than any of us. Tell us a little about how the first days, weeks, and months of the occupation were in East Jerusalem. What were the most important changes that you saw in the first days, months, or year?

Ziad Abu Zayyad: At that time, on June 5, 1967, I was the chief clerk/supervisor at the Jerusalem District Passports and Immigration Office, which was in the complex of government departments on Salah al-Din Street. The Israeli occupation turned the whole building in occupied East Jerusalem into the headquarters of the Israeli Ministry of Justice.

We knew about the war’s outbreak from the information desk, which was located at the entrance of the building. The employee there, who belongs to the Security Service office (mukhabarat), had a radio transistor and was following the news.

At around 10:00 a.m. there was a demonstration that included dozens of Jerusalem youths who marched to the building, shouting and demanding to be given weapons to defend themselves. And it’s worth saying that until that moment, civilians were prohibited from obtaining weapons by law. Jerusalem governor Anwar al-Khatib, whose office was on the first floor, came down and spoke to them. After calming them down, he said: “I don’t have any weapons here. Go to the muqata [the police complex in Wadi al-Joz]. You should do that.” So they went there.

One of my colleagues at the Passports Office, the late Salah al-Kharouf, suggested that we should try and catch up with them and see what would happen. We were young and full of pride, of military service age, but we had never been trained on weapons or allowed to obtain any. So we joined them, and when we arrived at the police complex and were standing at the gate, the young people were yelling, “We want weapons! We want weapons!” A jeep from the Jordanian army came, driven by an officer with the rank of colonel, and he asked the youths to be quiet and listen to him. “Please allow the army to do its job,” he said. “I am not going to tell you we have reached Tel Aviv, but I beseech you don’t disturb the army and instead go home.”

Salah asked me, “What do you think?” I replied ironically, “Okay, let’s go home.” And that was the last time I saw him. I was never allowed to go back to my office, even to pick up my personal belongings, including books and personal documents. The whole building was taken later by the Israeli army and it is now the Israeli Ministry of Justice.

What I am trying to say is that we were in a state of loss, a huge mess. No one knew what was going on. Even the governor of Jerusalem didn’t know what to ask us, or the citizens who were reporting to his office, to do. So some of the employees stayed until late in the day in their offices and some left.

I returned to my home in al-‘Izariyya [Bethany] on foot after the traffic was disrupted and chaos started to build up. As the intensity of the fighting intensified and the radio reports were too exaggerated and misleading, the people gradually began to understand that we were in a state of war. People took refuge in their homes, and some neighborhoods of Jerusalem and its suburbs began to be bombarded with cannons. Then in the following days, the Israeli army invaded the United Nations [UN] headquarters at Jabal Mukabbir, known as the “House of the High UN Commissioner,” and continued to other neighborhoods until it spread throughout most of them.

There were spot violent clashes with some members of the Jordanian army who refused to withdraw and fought valiantly until they were martyred as happened, for example, with the unit that was stationed in the corners of the Dominican Monastery on Nablus Road or in Sheikh Jarrah or in the Shu‘fat area, which the Israelis later called Giva’at Ha Tahmoshet [Ammunition Hill] because of the stiff resistance they faced in that area by the Jordanian army in a battle in the early hours of June 6, 1967. [In that battle, 36 Israeli soldiers and 71 Jordanian soldiers were killed.—Ed.] The Israeli forces also clashed with the units of newly recruited young men who were hastily trained shortly before the war, and they were almost all killed.

It must be said that the spirits of the people were very high, and their expectations were higher. Therefore, no one expected Jerusalem to fall so quickly. There were rumors that the Iraqi army was advancing, and when someone saw Israeli tanks, they thought they were Iraqi army tanks. One of the residents of Wadi al-Joz, when he saw the tank, carried cups of tea on a tray and went out to serve the tea to the soldiers under the assumption that they were from the Iraqi army, but they were Israelis, and they shot and killed him on the spot.

When the fighting stopped six days later, a curfew was imposed for 24 hours and then was gradually reduced to fewer hours each day to allow people to move around and meet their needs.

During the last days of the fighting and the first days after the ceasefire, some Arab doctors from East Jerusalem came out with their white robes and medical signs, such as the late Dr. Sobhi Ghosheh and the late Dr. Amin al-Khatib, and they gathered the bodies of the slain soldiers that were scattered throughout the city and buried them in mass graves.

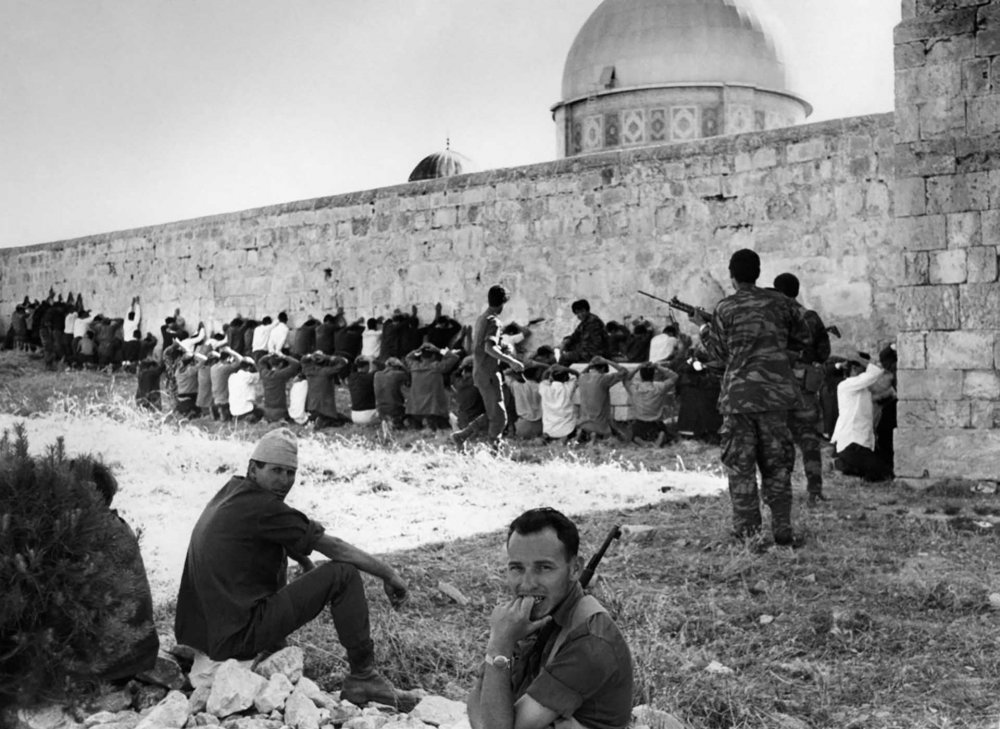

In the first days of the fighting, dozens of young men were arrested at random. Some were taken to detention centers; some were put handcuffed into open trucks to be paraded through the streets of West Jerusalem for the Israelis to see and greet them with shouts of contempt and curses.

When the Israelis occupied East Jerusalem, they did not expect that their occupation of it would be prolonged, and therefore they tried to use the reality of the war to impose some facts of the ground. For example, there was no plaza in front of the Western Wall; rather, directly in front of it was an ancient Maghrebi neighborhood called Waqf Abu Madein that was a Moroccan family waqf endowment. It had the only plastics factory in the West Bank, which was owned by the late Hajj Hussein Abedin. So the Israelis loaded the residents of this neighborhood into trailers and moved them to some neighborhoods outside of Jerusalem such as al-‘Izariyya. Then the Israeli bulldozers razed the houses of this neighborhood, including the factory and the machinery inside it, and reduced it to rubble and moved the rubble outside and turned the place into the plaza that one sees today in front of the Western Wall, the Wailing Wall Plaza.

Hajj Hussein Abedin tried to stop the demolition by protesting to the Israeli officials, but they misled him and intended to waste time until the mission was accomplished.

For example, he went to the municipality, and they told him to go to the Israeli governor of Jerusalem. He went to the governor, and he told him to go to the police. He went to the police, and they told him to go to the military governor—and so on.

Still, people in Jerusalem lived in hope and believed that the United Nations would soon force the Israelis to withdraw, and therefore they did not deal with the situation with the degree of seriousness that later became clear. As a result, owners of the shops and stores accustomed to welcoming foreign tourists in the city of Jerusalem treated the Israelis who flocked to Jerusalem as if they were tourists.

Daoud Kuttab: Khalil, your father was killed in the first days after the war. Tell us what happened.

Khalil Assali: What happened is that on that fateful day my father was martyred near our family home. As Ziad said, Wadi al-Joz was a point of activity and movement, as the police headquarters at the Rockefeller Museum was located near it; my father’s uncle, who was also martyred on the same day, was working there. A few hours after my father’s death, a Jewish sniper was standing there and shot at all people who were moving. He killed a large number of young people, some of them are still buried in Wadi al-Joz, and even the names of some of them are unknown, including Jordanian soldiers and school students. I was only four years old at that time.

Ziad Abu Zayyad: And here I want to add two important points, the first of which is that after the occupation of East Jerusalem, the Israelis flooded our markets in an unprecedented manner, so much so that one of them told me that he was surprised by the existence of BIC ballpoint pens, as he reflected on the amount of progress that East Jerusalem was experiencing. This leads me to the second point, which is that during and after the 1948 Nakba, Jerusalem lost its commercial and economic center, which was in the [New City in the] Mamilla area and Jaffa Street and others [because those areas were taken by Israel and made part of West Jerusalem in the newly declared state—Ed.]. After the 1948 War and thanks to Jordanian efforts, the economy and markets in East Jerusalem and the Old City were revived. After the 1967 War, however, the economic situation worsened in East Jerusalem without meaningful recovery, and the glory of Jerusalem as a world capital receded.

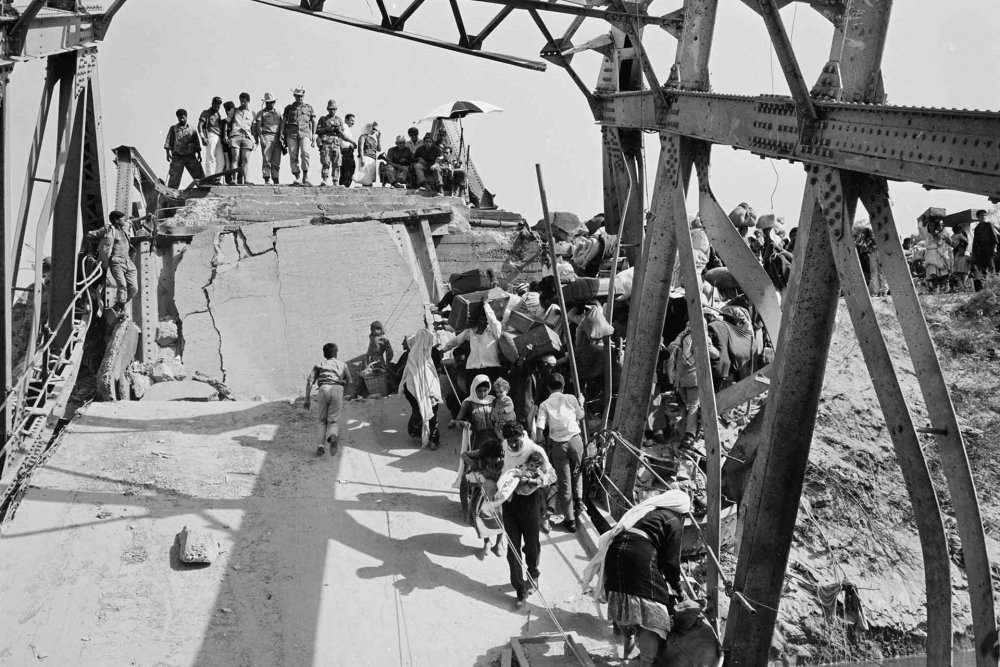

Daoud Kuttab: I would like to talk about my personal experience. I was 12 years old and home alone with my siblings. My father was in Germany and my mother was in Jerusalem. My brother Jonathan was not home. There were Jordanian soldiers next to our house. We bought them some coffee that morning, but later we heard a siren. I was sitting relaxed on the balcony when my brother came in saying that the war had begun and ordered us to go to the basement. I thought that the siren was a drill, not the real thing. The important thing is, of course, while we were hiding in the basement of the house, we heard on the radio that Egypt had shot down tens of Israeli planes. All this was lies. We saw people with their families and belongings walking toward the center of Bethlehem; we decided to do the same. I remember that my youngest sister had stepped on a nail so Jonathan had to carry her, while I carried our baby sister. We walked about three kilometers, and we reached my aunt’s house in the center of Bethlehem.

At our aunt’s home, my cousin Mubarak Awad began a one-man effort to convince people not to leave their homes. We were hearing on loudspeakers calls for Palestinians to leave, but Mubarak, whose father was killed in 1948 and whose family had suffered a lot since, wanted to be sure that people don’t turn into refugees or perhaps die on the way. “Don’t leave, don’t leave, don’t leave your country,” he urged. I am sure that maybe 100 people turned back based on his pleading.

After the war, when we returned to our house near Rachel’s Tomb, we saw that the Jordanian soldiers had left the cups and coffee pot at our house’s steps. As kids, we started selling lemonade to the many Israelis who were coming to the site at the entrance of Bethlehem.

Ziad Abu Zayyad: We, as a Palestinian people, did not have any say in what happened or what was happening. Young men who were of army age were not trained at all in weapons and did not have weapons with them, and when Jordan wanted to join the war, they rapidly conscripted young men but few were given weapons or basic training on how to use these weapons. Most of those young untrained soldiers were killed in the Wadi al-Joz area. Jordan was not ready for war. There was a process of emotional agitation, and King Hussein was at odds with [Egyptian President] Gamal Abdel Nasser, but he got on the plane and went to Egypt, and we began to sing that we would return by force of arms. We were relieved that Jordan had started planning the war, but it had no readiness or preparations to participate in this war. Shortly after the outbreak of the war, the army withdrew, mostly in an irregular manner, but it must be said that we witnessed individual heroics in Jerusalem by several members of the Jordanian army who continued to fight to the extent that they were martyred and refused to withdraw, and I witnessed some such cases.

On the second day of the war, we took refuge in the Roman Orthodox Monastery in al-‘Izariyya. I was standing on the street, and people were traveling from Jerusalem towards Jericho and Jordan, and I too was trying to convince people not to emigrate. I gathered in the Orthodox holy site a few hundred of those whom I was able to persuade to enter the monastery because it is a safe place, and we were awaiting a ceasefire. And I remember that one woman from the Abu Tur area came up to us, and she was wearing house clothes, and she said, “Right in front of me, the Israelis lined up men on the wall and shot them.” When she started talking like this, many people decided to leave for Jordan. In the end, we found out that what she had said was all a lie.

The problem of the people of Palestine is that until today we have not had any real role in making the fateful decisions regarding our future as a people, and we are constantly forced to accept what others impose on us, whether they are governments or party activists or even from Palestinian factions, many that do not have a broad popular base representing the entire Palestinian people.

But the reality is that we were left without leadership and our crisis is a crisis of lack of leadership from that time until today.

Reverberations of the Naksa in Today’s Jerusalem

Daoud Kuttab: Allow me to fast-forward for Maurine, who is younger than we are, because you certainly haven’t lived those days. We would like to talk a little about the current situation, that is, when you received the position of acting director of the Yabous Centre. How do you see the artistic and cultural situation in Jerusalem?

Maurine Kouba: Sure, I hear talk about the 1967 War—that is, your narration of the reality that happened at the time of the Naksa or the Nakba—which I used to hear from my ancestors. I, like others, experienced these stories, which were told to us over and over—scenes we are currently witnessing again today [in Gaza].

As to the artistic and cultural scene, the city of Jerusalem has gone through various stages. Jerusalem has seen a change in the cultural rise and fall on different levels, and there have always been periods where there was a recovery in the cultural sector and artistic activity, while at other times it went through periods of a kind of suppression or slowness in this scene. This is normal, and I think part of the reason is the isolation of Jerusalem and the interruption that has been forced upon the city and its people [by the Israel occupation, through, for example, the closure of the West Bank, the Separation Wall, the permit regime, etc.—Ed]. As for the rest of the Palestinian cities, whether in the West Bank or in the 1948 territories, some cultural centers and institutions carry out activities in addition to the limited and few cultural institutions operating in East Jerusalem, and they persist despite great challenges, whether political, economic, or even social.

This sector is an integral part of Palestinian life in Jerusalem, because Jerusalem is the capital of Palestinian culture and this did not happen in a vacuum.

Ziad Abu Zayyad: I disagree with you. Jerusalem experienced a cultural and artistic renaissance in the 1970s and 1980s. At that time, we saw the emergence of Palestinian theater companies like el-Hakawati and its director Francois Abu Salem, and the musician Mustafa al-Kurd, who became famous for the song against emigration “Hat al-Sikkeh, Hat al-Mangal.” Jerusalem experienced a great artistic and musical renaissance until the early 2000s [with the completion of the Separation Wall], after which things went very bad.

Daoud Kuttab: There is no doubt that the Oslo Accords and the Separation Wall played a large role in the decline of Jerusalem, but the biggest thing in my opinion is the absence of any significant leadership after the death of Faisal al-Husseini on May 31, 2001. There are a lot of organizations that are supposed to work for Jerusalem, but no leader has emerged who can gather people around him like Faisal could. There may be a need for some form of election to help bring about new leadership as happens among Palestinian citizens of Israel. Elections are a mechanism for the ascension of leaders, but we have no elections except Palestinian national elections and those have not been held since 2006 under the pretext that the people of Jerusalem will not be allowed to vote in Jerusalem-based post offices.

Ziad Abu Zayyad: It is not true that the elections are the only way out. They may be one of the means, but leaders like Faisal al-Husseini had a charisma that we do not see today. The elections among Palestinian citizens in Israel did not produce leaders. Leaders such as Tawfiq Ziad, Emil Habibi, Tawfiq Toubi, and others emerged without elections. We at al-Fajr Arabic newspaper, when I was its editor, played a major role in supporting and encouraging the rise of national leaders supporting the Palestine Liberation Organization [PLO] and we helped to elevate people such as the mayor of Nablus, Bassam al-Shaka‘a, and the mayor of Ramallah, Karim Khalaf, and other national leaders at that time.

Ahmed Safadi: Brother Faisal al-Husseini was the emir of Jerusalem and a universal figure who succeeded in uniting Palestinians of various political affiliations. He was a real leader who paid attention to the issues and concerns of the people of Jerusalem. Despite the length of time since his departure, no one can forget his role and his defense of Jerusalem. Jerusalem may feel the loss of a great leader who cannot be replaced.

There is a need to institutionalize the work so that society can replace the individual and the energy would be better as a group than as an individual. This is the way to honor Faisal al-Husseini.

We need to exert our energies collectively, and that is how we can produce results. We need to walk in the footsteps of the late Faisal al-Husseini.

Daoud Kuttab: Today in Jerusalem you experienced the so-called Flag March, which includes many provocations by Jewish extremists to the residents of the Old City. Tell us what happened.

Ahmed Safadi: On this day there was special attention to what the occupation calls the “reunification” of Jerusalem. However, it is the Israeli occupation and the commemoration of the occupation, the massacres by military force through space, and the freedom given to settlers under the protection of the occupation army that cause havoc.

But the injection of this artificial Israeli presence doesn’t provide the Israelis with genuine connection and control. A few hours after those marches ended, the city returns to its normal buzz of life. Its inhabitants, its stones, its markets all come to life and they reflect that the city is an authentically Palestinian Arab one.

Daoud Kuttab: I would like to know from Maurine what you think about the impact of social and health privileges that Palestinian permanent residents who reside in Jerusalem have. Did they increase the isolation of the Jerusalemites or is that exaggerated?

Maurine Kouba: Not everyone understands that the privileges that Jerusalemites get are in return for their payment of taxes and other fees. When we get national insurance, we get it because we have been paying into the national insurance fund. Same for health insurance and other items. We pay high taxes and national insurance and arnona, in addition to other things, and this is the tax paid in order to maintain our residence in Jerusalem and the limited rights deriving from it. Still with everything, Jerusalemites face a constant risk of losing their residency and their rights [through residency revocation by the state—Ed.].

Ziad Abu Zayyad: My house in al-‘Izariyya is large in terms of space. If it was in Jerusalem, I would not be able to live in it, because the property tax is calculated based on the size of the house. So, when West Bankers talk about the special privileges that Jerusalemites enjoy, the story is not like this, but what bothers me is the social gap and even the chasm among intellectuals that takes place between the Palestinians in Jerusalem and those in the rest of the West Bank.

In my opinion, the closure of Jerusalem and the isolation of Jerusalem from the West Bank is the biggest problem that Jerusalem and Palestinian Jerusalemites face.

Daoud Kuttab: Maurine, I would like your opinion. I would like to know about relationships between Jerusalemites and other Palestinians in cities in the rest of the West Bank, such as Bethlehem or Ramallah.

Maurine Kouba: It is true what Mr. Ziad said about the effect of isolating Jerusalem from the rest of Palestine in particular. Over the years, a difference in behavior has developed, whether one is in Jerusalem or in the West Bank. The question is how Jerusalemites were treated in the rest of the cities of Palestine. Do they feel discriminated against? Do Jerusalemites act differently?

Daoud Kuttab: It’s time to wrap up. What are your concluding thoughts, each of you?

Ziad Abu Zayyad: Personally I am completely convinced that the true national spirit still exists in Jerusalem and exists among the Jerusalemites despite all the temptations and pressures they are subjected to, and I am confident that at the moment of a national test, Jerusalem and its people will prove that it and its people are the heart of the Palestinian people and that its political and national stance cannot be affected by any Israeli incentive.

Ahmed Safadi: It is necessary to agree to resistance and survival strategies for merchants and residents and investment in education and housing to resist the occupation’s plans in reality and not in words, and this was the essence of Faisal al-Husseini’s interest in the development of sectors in Jerusalem—to break the dependence on the occupation. Until now, we have been missing from the successive Palestinian governments genuine support due to the political agreements by which they are bound.1 Palestinian institutions in Jerusalem must therefore be developed to play a compensatory role for the authorities.

Khalil Assali: Yes, Jerusalem is really the heart of Palestine and it is really the one that is standing now and it is the one that preserves the Palestinian identity as much as possible and is required to work together in order to continue with this focus on preserving the Palestinian Arab narrative in Jerusalem.

Maurine Kouba: Jerusalem is suffering and its pain is increasing, but its faith lies in in its people and the people’s hope for Jerusalem is still growing. If there was no hope, Jerusalem wouldn’t be here now. Jerusalem exists and stands strong, and the people still have strength. As I said, our identity is there, and we are working on this issue through culture and education. By raising awareness in all the different fields, we’re strengthening this national identity in Jerusalem so we can continue and we can reach liberation.

Daoud Kuttab: Thank you very much, everyone.

Notes

Under the terms of the Oslo Accords of the 1990s and subsequent Israeli laws, the Palestinian Authority (PA) in Ramallah is banned from operating within the Israeli-defined municipal boundaries of Jerusalem. Israel takes this ban extremely seriously to the point of criminalizing any PA involvement inside Jerusalem.—Ed.