The Maghreb (meaning “the place where the sun sets” in Arabic) is a region of northwest Africa that lies along the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. It has existed in different forms since the eighth century. Today it comprises five countries: Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and sometimes Mauritania. In Arabic, the name for Morocco is also Maghreb.1

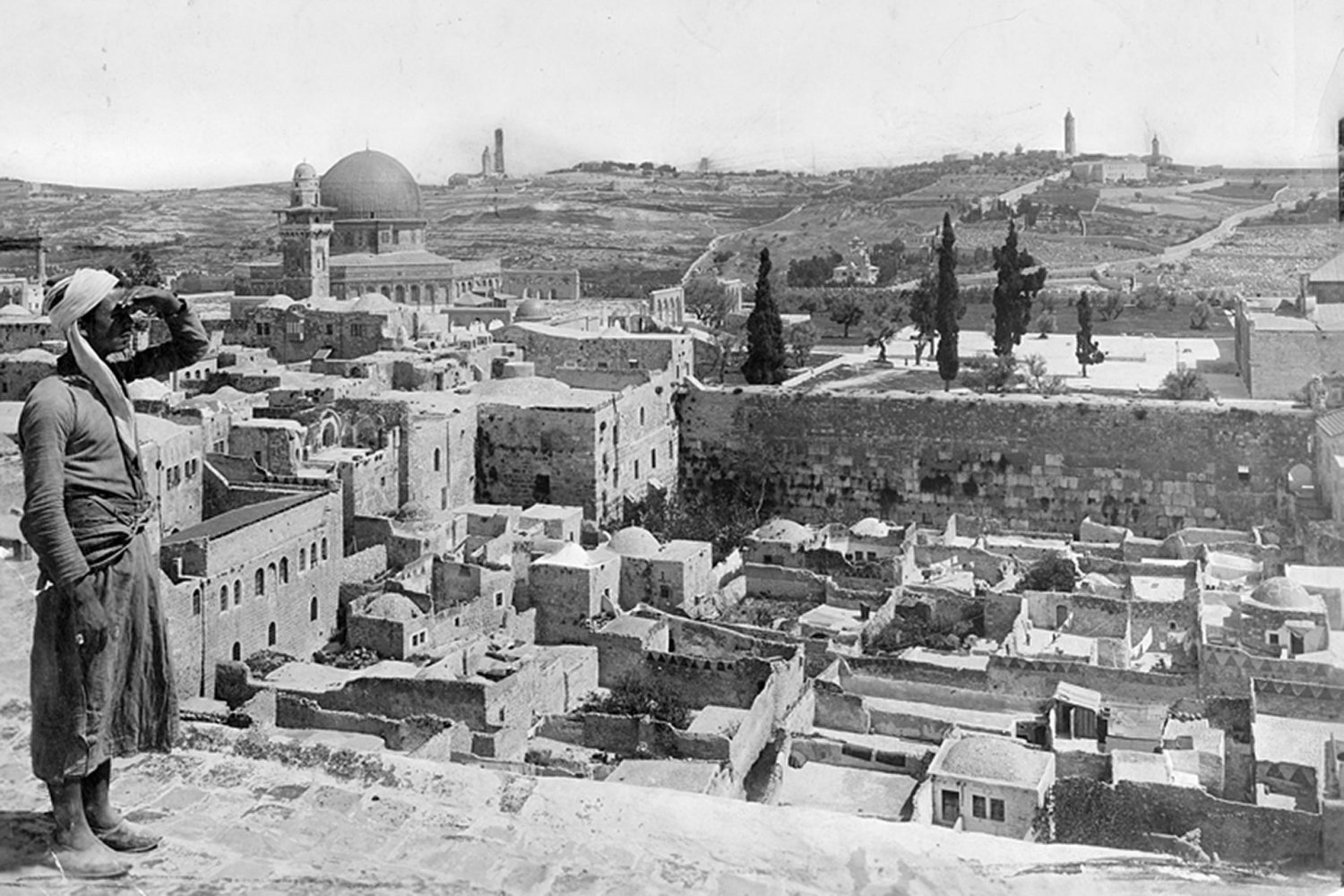

Pilgrims from this region first arrived in Jerusalem in the late 10th century.2

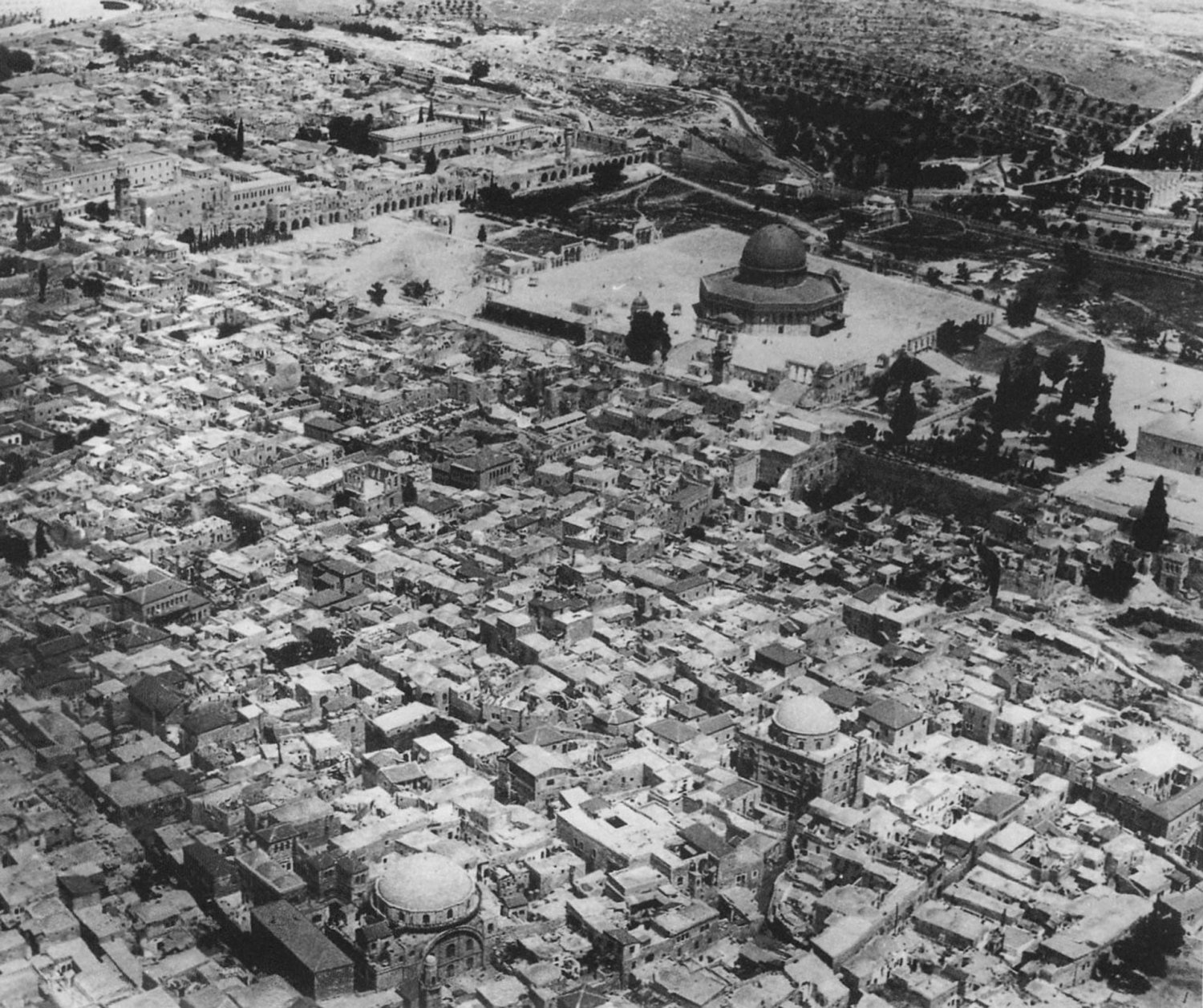

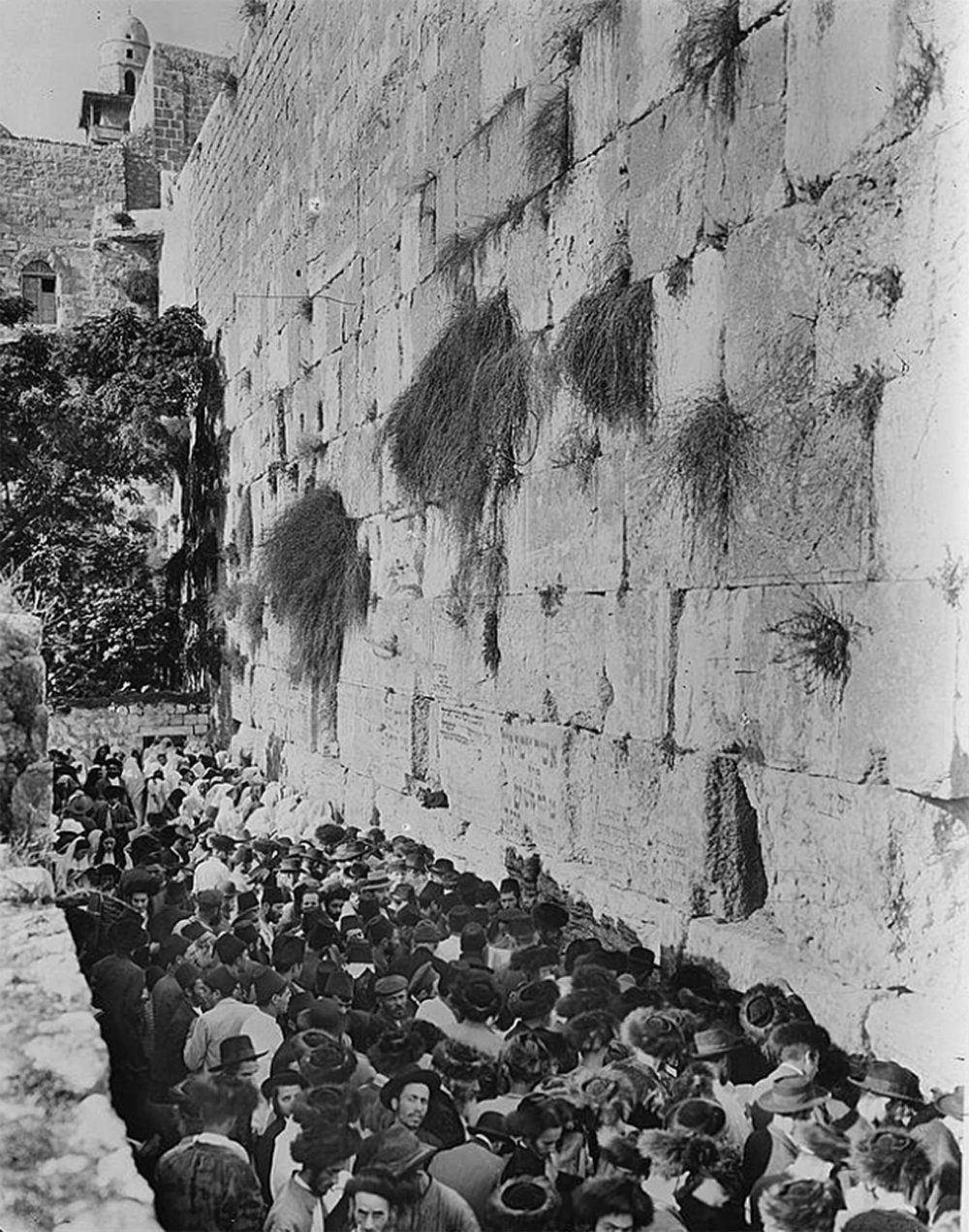

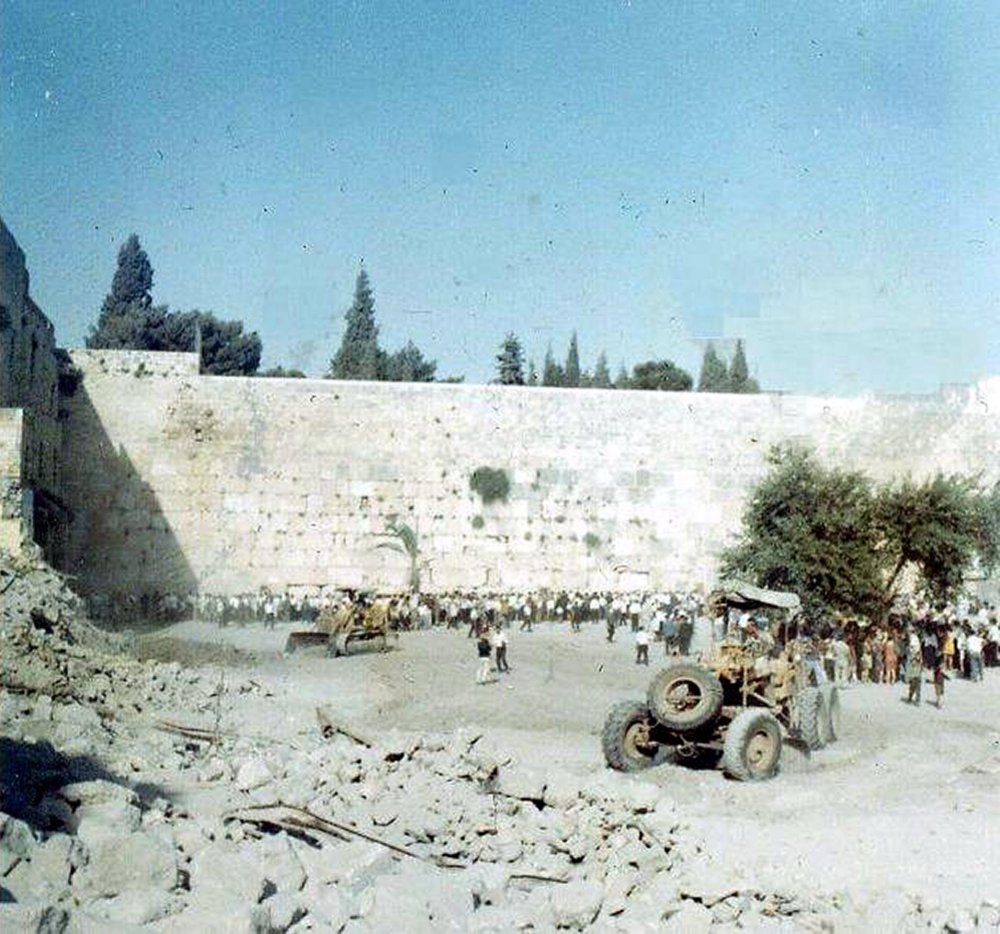

In 1187, the Kurdish warrior Salah al-Din al-Ayyubi conquered Jerusalem and ousted the Crusaders. To reward the many Maghrebi and southern Spanish soldiers who fought in his army, Salah al-Din offered them parcels of land around the Western Wall.3

Several years later, in 1193, his son Afdal, who was governor of Damascus (which included Jerusalem at the time), endowed the quarter as a waqf to the Maghrebi community. The designated purpose of this waqf was to provide accommodation for arriving Maghrebis “without distinction of origin,” including pilgrims and those fleeing oppression at home.4 The generous endowment read, “For the benefit of the community of Mughrabi of all description and different occupations, male and female, old and young, the low and the high, to settle in its residences and to benefit from its uses according to their different needs.”5 Documentation from the time establishes that “Maghrebi” was defined as immigrants from western Tunisia, Algiers, and Morocco.6 In practice, this meant that any Maghrebi person who wished to reside in the quarter would be welcomed.7