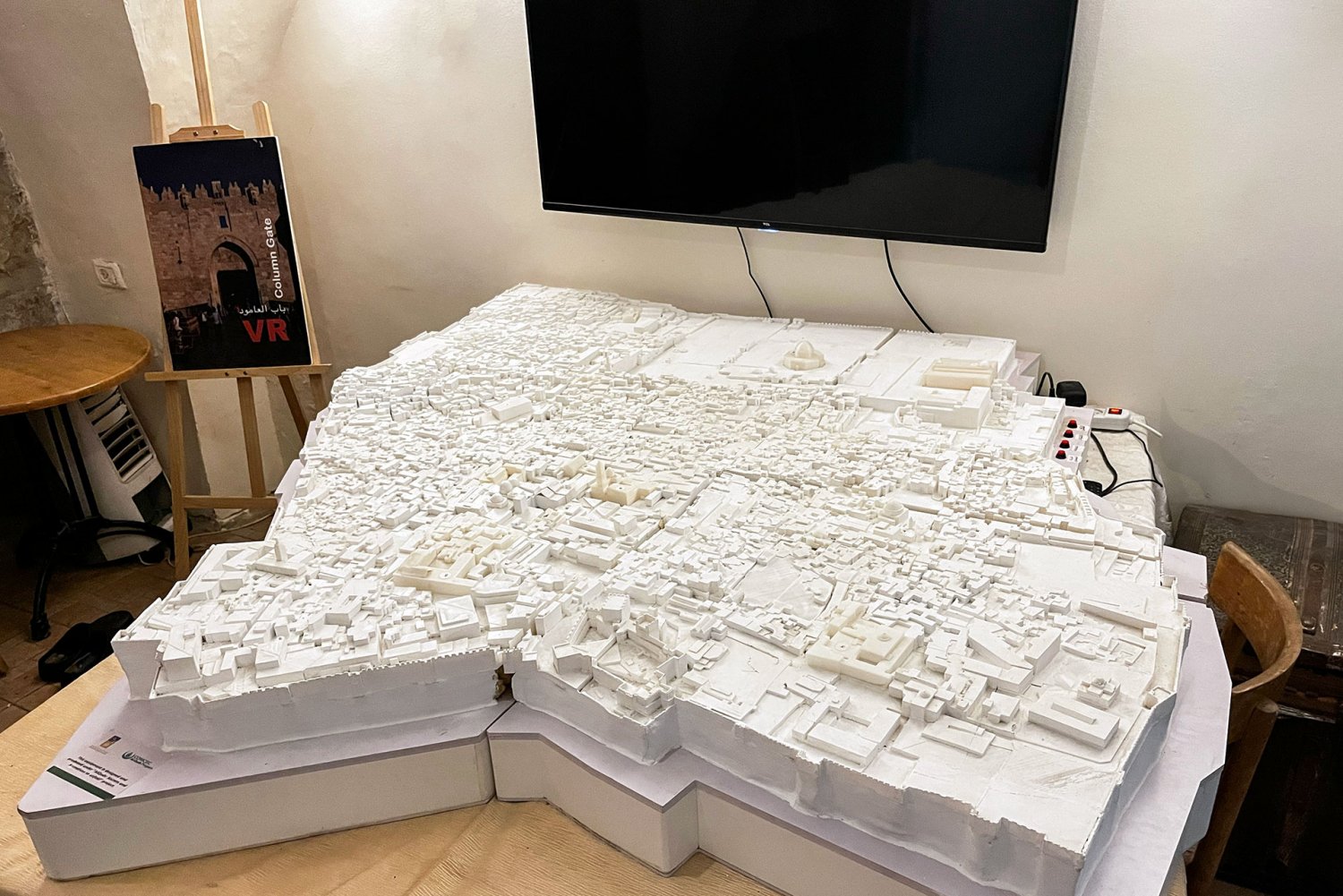

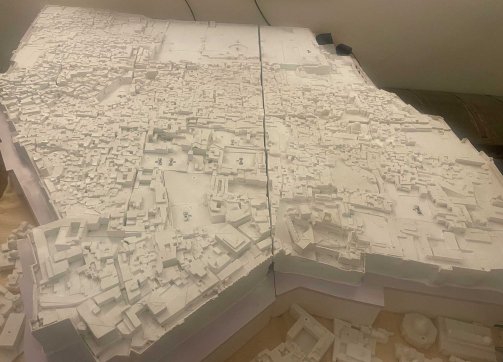

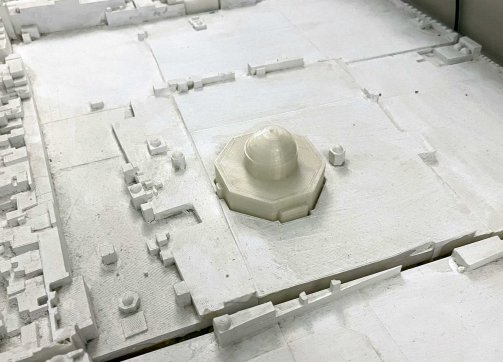

Go down the steps of the Jerusalem Hotel in East Jerusalem and you’ll find an installation that illuminates the multifaceted cultural identity of Jerusalem. The interactive, three-dimensional model of the Old City of Jerusalem comes with an electronic screen that offers historical information about 26 different sites, communities, and architectural landmarks, each represented by a puzzle piece. Pick up a piece—say, al-Aqsa Mosque—and the screen automatically lights up and provides an explanation about it.

Credit:

David Silverman, Getty Images

“We Do Not Describe Jerusalem—We Interpret It”: Raed Saadeh and His Model of Jerusalem

The plastic, 2 x 2 meters, 3-dimensional model was created in 2022 and is available for Jerusalem Hotel guests, friends, and visitors to use. (It is marketed softly through tour guides.) It will most likely be moved to Khan Tankaz, a huge Mamluk-era caravanserai that is representative of Palestinian cultural heritage and located in the middle of the southern wall of Suq al-Qattanin (the Cotton Merchants’ Market).

On May 21, 2024, Jerusalem Story met with Raed Saadeh, the owner and general manager of the Jerusalem Hotel and the executive director of the Jerusalem Tourism Cluster, an organization that is concerned with the development of tourism in Jerusalem specifically. Raed was eager to demonstrate what the model could do: He picked out certain pieces, such as the Armenian Convent of St. James and the Church of St. Anne, and asked the author to guess which puzzle pieces these represented.

Although some pieces are easily identifiable (such as the Dome of the Rock), it gets a little trickier to guess some of the others. (The Old City of Jerusalem has a good number of mosques and churches; differentiating one from the other is not such an easy task.) The model doesn’t leave users in the dark, however: It is connected to a screen, which lights up and provides easy-to-read explanations of each piece lifted from the base.

Multidimensions of Jerusalem: Mosaic of Marum

Born and raised in Jerusalem, Raed is personally invested in his beloved city and its cultural heritage. Although he is mostly known for his work in community tourism and cultural preservation in Palestine (he happens to be co-founder and chairman of the Birzeit-based Rozana Association for Architectural Heritage Conservation and Rural Tourism Development) and is active in leading cultural and arts associations in Jerusalem, Raed’s educational background was in mechanical engineering: He received a bachelor’s degree from Syracuse University and a master’s from Case Western Reserve University. He casually mentions that he designed and created this model of Jerusalem himself.

He was motivated because, as a Jerusalemite, he felt responsible for the presentation of the city’s cultural heritage to the world. The city has a long and complicated history, one to which all three monotheistic religions have contributed. Jerusalemites are well-equipped to preserve the city’s cultural strands.

He explains that he posed the hypothetical question to himself: What is Jerusalem? He realized that he thought of the city as a mosaic, and his installation attempts to convey the variety of the city’s religions and ethnicities, using the mosaic metaphor.1

In addition to the educative and touristic functions of the model, Raed believes it challenges stereotypical depictions and enhances the imagination and curiosity about what Jerusalem is. The model makes it possible for users to understand the city through an interpretive method rather than resorting to overused and inaccurate expressions (such as “the Holy Land”).

As a fellow Jerusalemite, I always find it captivating to muse on a panoramic view of the city with its many doors, narrow streets, disguised shortcuts, and intriguing sites. The historic connections are especially riveting: Marveling at the awe-inspiring model makes one think not only of a city, but of the countless identities that the city has embodied across the different eras. With curious eyes and an open mind, it becomes impossible to proceed with the impression that such a vast city with its multifarious ethnic traditions could be reduced to four simplistic quarters.

Raed’s search for a meaningful way to describe his city without relying on clichés resulted in the installation he named “Mosaic of Marum.” Marum is derived from the concept of the seven skies (or heavens) in Islam: “Each of the seven skies has its own name and color. Marum happens to be the third sky, and it is the color of light. Instead of saying ‘lightness,’ or ‘holy,’ I went for Marum.” He deliberately avoided using words with religious connotations so as not to limit the experience of the city to its religious dimension; his goal is to deepen our reflective and interpretative understanding of the city.

Raed believes that going for interpretive methods (rather than restrictive descriptions) might challenge viewers to ponder the city’s cultural diversity and become curious about its poetic, multilayered, and personal meanings.

“Four Quarters of Jerusalem”

Much as the description of Jerusalem as “the Holy Land” is restrictive, so too is the assumption that the Old City of Jerusalem has four quarters, Raed explains.

He sneers at the suggestion that there are four, or even seven or nine quarters in the Old City of Jerusalem: “More like 25 neighborhoods!” He finds that the seemingly plausible division into four quarters had been illogical from the get-go: George Williams, who was chaplain of the first Protestant bishop of Jerusalem (Michael Alexander) in the 1840s, Raed mentions, was the one who had come up with the idea in the mid-19th century. In his view, and as Matthew Teller, author of Nine Quarters of Jerusalem, extensively explains, Williams—with a colonial mindset—must have opted for a quick fix on how to understand the Old City, and so he conceptualized it as an entity with four quarters, with the assumption that each of the four ethnic/religious groups (namely, the Muslim, Jewish, Christian, and Armenian) could be lumped up into one cluster.2

“Even the local inhabitants may fall into this trap,” Raed explains. “But our deeper study shows us that there is no way things could be this simplistic.” After all, “what had been assumed to be the ‘Muslim Quarter’ has a larger number of churches than those in the ‘Christian Quarter’! Meanwhile, the ‘Christian Quarter’ has six historical mosques (such as al-Khanqah al-Salahiyya Mosque and the Omar Ibn al-Khattab Mosque).”3

It also makes one wonder why the Armenian Quarter stands out, he observes, seeing that there is not just one but two Armenian neighborhoods in Jerusalem (the Apostolic and the Catholic)—let alone the tens of other communities and neighborhoods, such as the Assyrian, Afghani, Coptic, Ethiopian, Indian, Greek, Austrian, Russian, Moroccan, Swedish, Italian, Maronite, and Naqshbandi neighborhoods.4

Heritage Is Identity

Living in the city that he loves, Raed makes it his mission to provide visitors (including residents) a unique glimpse into its cultural and architectural heritage of Jerusalem through various means. More recently, those have taken on an interactive nature.

The “Mosaic of Marum,” which the Jerusalem Tourism Cluster brought to life in collaboration with InterTech,5 is one of three interactive experiences currently available at the Jerusalem Hotel.

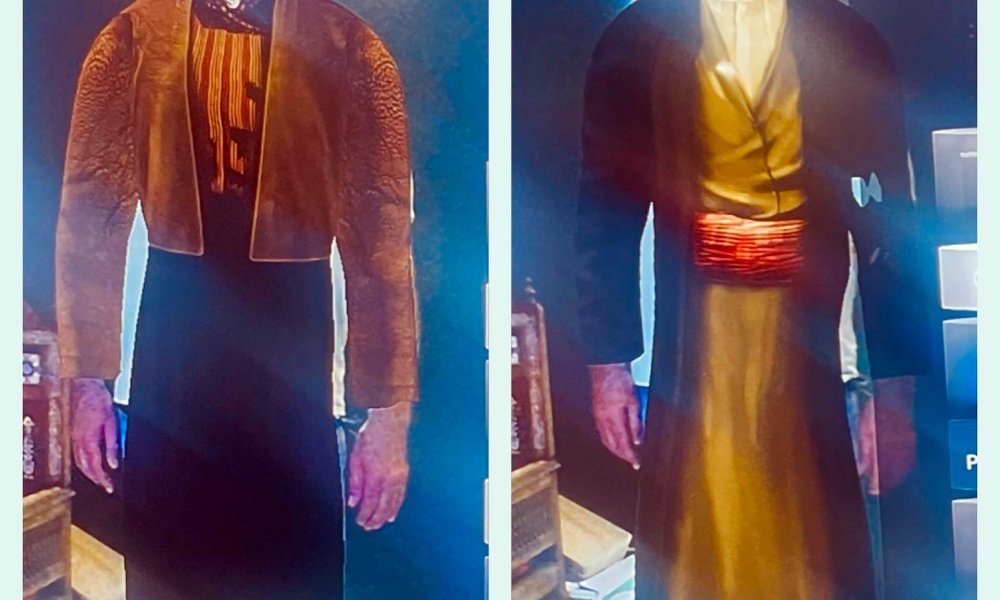

The “augmented reality mirror” allows visitors to stand in front of a mirror, pick out a costume worn in Jerusalem over a selected historic period, and see what they would look like in that selection. This innovative use of technology is an entertaining way to learn about the cultural heritage of Jerusalem.

The “virtual reality (VR) headset” transports wearers into a different time and place in Jerusalem, such as Bab al-Amud during the Crusades.

This is probably the closest that most people will get to time travel, and the experience might leave them with a sense of wonder regarding the past and the unfolding future of the awe-inspiring place that is Jerusalem.

Notes

Paley Center, “Artistic Gatherings: Cultural Activist Raed Saadeh” [in Arabic], April 15, 2023.

Ida Audeh, "Stories from the Old City: Matthew Teller’s Nine Quarters of Jerusalem,” Jerusalem Story, August 23, 2022.

Paley Center, “Artistic Gatherings.”

Paley Center, “Artistic Gatherings.”

“Jerusalem Tourism Cluster and InterTech Unveil ‘A City Tale’ Exhibition,” InterTech, accessed May 23, 2024.