A 200-year-old seminary that sheltered hundreds of children orphaned during the Armenian Genocide over 100 years ago has been converted and renovated into a newly refurbished Armenian museum in the Armenian Quarter of the Old City.

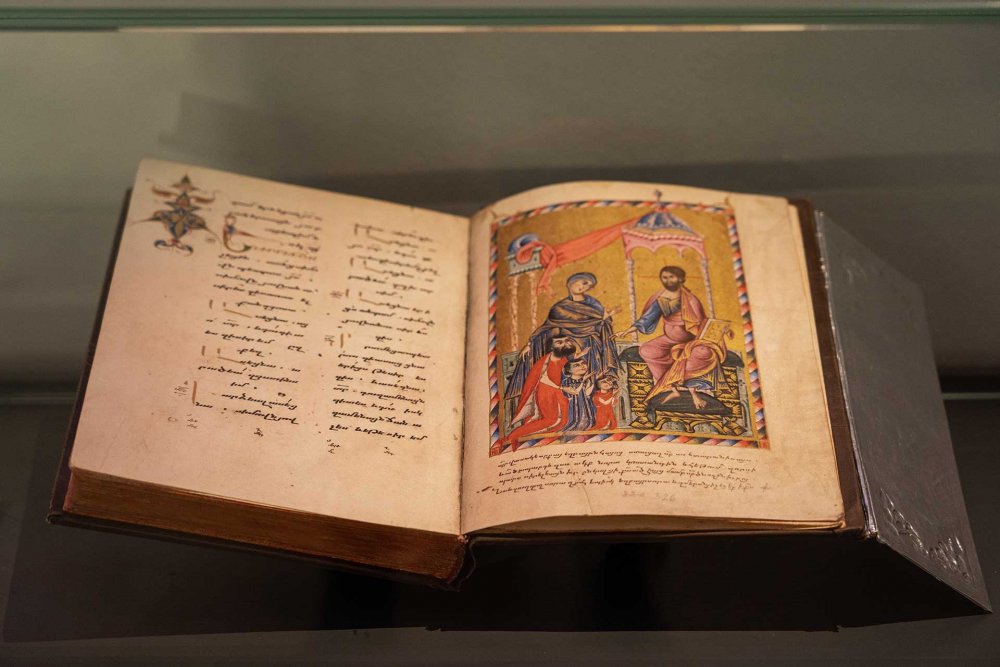

The Armenian Museum of Jerusalem opened its doors at the end of 2022 after almost a decade of renovation. The museum covers 1,600 years of art, culture, and history of Armenians in the Holy Land. Among its holdings are jewel-encrusted exhibits and manuscripts dating back to the 10th century.

With somber prayer playing in the background, the museum also tells the history of the Armenian Genocide and the survival of a people.

The compound, built in 1853, had been used as the Armenian Patriarchate’s theological seminary’s dormitory. As of 1969, it was established as a small museum, yet it was closed for several years and needed organization of its collections.

Thanks to a generous donation by the Mardigian foundation, the Edward and Helen Mardigian Museum of Armenian Art and History was renovated in 2022. Three renowned French Armenians—Claude Mutafian, mathematician and medieval Armenian historian; Harout Bezdjian, producer and former head of the audiovisual division at the Centre Pompidou; and Raymond Kevorkian, historian and leading scholar of the Armenian Genocide—led the effort to bring the museum to life. Theirs was the difficult task of combing through more than 25,000 artifacts gifted to the Armenian monastery over more than a thousand years and selecting the ones that could tell the story of the Armenian community in Jerusalem.

At its current stage, the museum has a new roof and contains two floors. The entrance presents a precious mosaic floor (described in more detail below), and the first floor has rooms showcasing the rich history of the Armenians in Jerusalem. By and large, the museum chronicles the history of Jerusalem as a city and the transformations it underwent in the Roman, Byzantine, Mamluk, Crusade, Mongol, Ottoman, and British Mandate eras.