Feast of Ashes: The Life and Art of David Ohannessian, by Sato Moughalian. Stanford: Redwood Press, 2019.

***

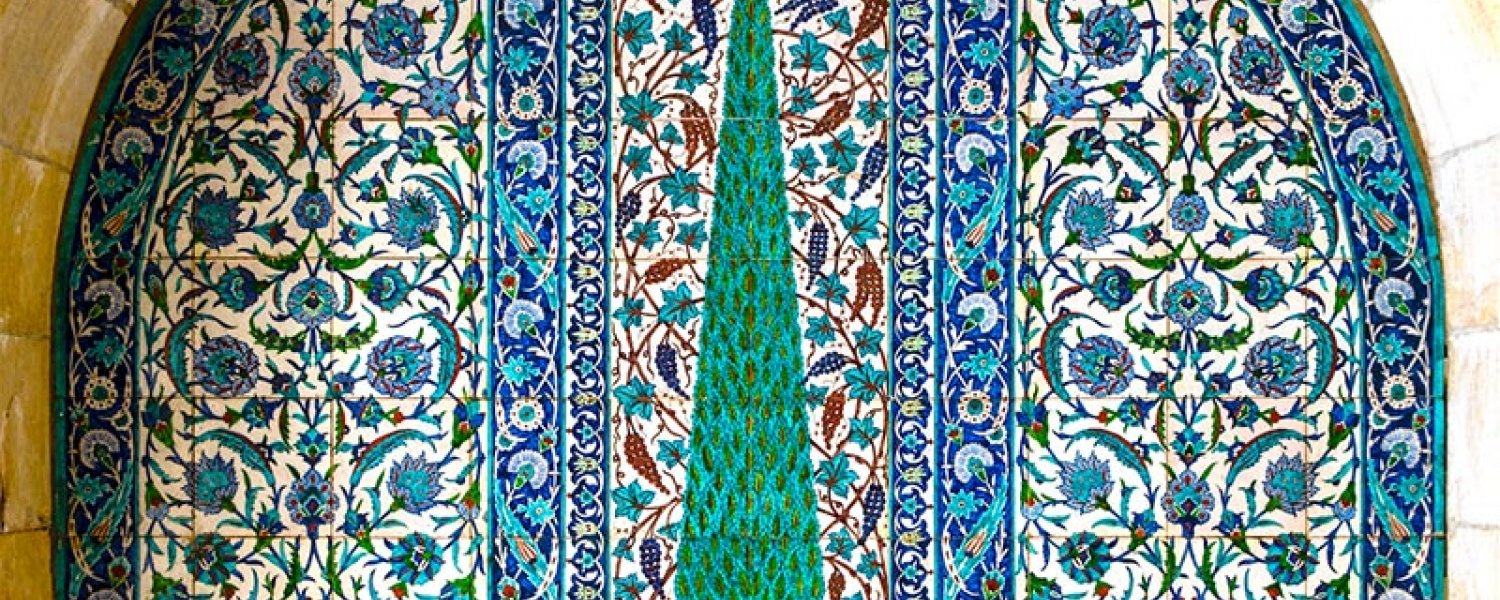

At the end of 1918, an Armenian genocide survivor who had trekked from Turkey to Syria with his family had a miraculous stroke of good fortune. This chance, which came about due to his unique and prodigious talents as a master ceramicist, would bring him to Jerusalem, where he would go on to transform the city’s arts and culture in a fundamental way.

The fascinating story of David Ohannessian, the subject of Feast of Ashes: The Life and Art of David Ohannessian, is told by his granddaughter, Sato Moughalian. An Armenian American flutist with no direct experience of the family’s Jerusalem years (or even of her grandfather, for that matter), her interest in her family’s history developed slowly, fed by a few disparate factoids: the sadness and silence that periodically came over her parents when memories of their past intruded on the present; her mother’s written account of her family’s history, drawing on the recollections of her six siblings; her aunt’s list of her father’s commissioned works; her readings about the Armenian genocide; and a few pieces of pottery created by her grandfather that were in the family’s possession.