Five friends get together for a drink at the King David Hotel in Jerusalem. The date is July 21, 1946, and they are celebrating the one-year wedding anniversary of Walid and Rasha Khalidi, who will be leaving Jerusalem the next day. Despite the political unrest in the city, the five are in a festive mood—they are young, healthy, and educated, two of them are happy newlyweds, and none of them has reason to think that their future might not be theirs to shape. That is how at least one of the participants remembered the event decades later (though hindsight can be inaccurate, as one of the friends had already left the country by then).

Credit:

Columbia University Press

An “Ecumenical” Friendship in Mandate Palestine, Ruptured by Politics

The following day, Jerusalem is rocked by an explosion that demolishes the southern wing of the hotel, which housed the administrative offices of the Colonial British Mandate. Members of the Zionist paramilitary group, the Irgun, carried out the terrorist attack, killing 91 and injuring 69. By 1946, British and Zionist forces, who had collaborated to suppress Palestinian rebels during the 1936–39 Great Palestinian Revolt, were now fighting one another. The Zionists calculated that the British would eventually withdraw from Palestine if the price was high enough, and their departure would leave the country open for conquest by the well-armed, well-organized, and well-funded Zionist militias to create their exclusivist ethnonationalist state—at the expense of the indigenous non-Jewish Palestinians.

The bombing of the King David Hotel marked a turning point in the colonial struggle over Palestine. The author describes the significance of the bombing on the five friends as follows:

The bombing literally blew apart the very ground that brought together the ecumenical circle, and more precisely the individuals at the heart of this book, from under their feet. It figures as the event—anticipating more violent events to come—that rendered their continued friendship impossible and as a metaphor of its dissolution as they were dispersed around the globe.1

The author’s use of the descriptor “ecumenical” in fact comes from Walid Khalidi, one of the five friends, who many years later used the term to refer to the composition of the group: two Muslims, two Christians, and one Jew. By the 1940s, it would have been uncommon for Arab Jerusalemites and Jews to socialize in this way, even though neighbors routinely visited one another on religious holidays and other occasions. In fact, in memoir after memoir, Palestinians reminiscing about life in Jerusalem and beyond before the Nakba frequently stress that they socialized with others irrespective of their faiths.2 Indeed, it is a detail that invariably comes out, an implicit lament by those who paid the price for the Nakba, as they watched with dismay the transformation of a diverse, multicultural, interwoven society into one crudely segregated. In one of many ironies, the secular Zionists who colonized Palestine tended to establish their own, semi-gated homogenous communities, schools, and political institutions, apparently viewing the commingling of communities as counterproductive to their ethnonationalist goal, even as those they regarded as primitively sectarian regarded those interactions as entirely normal in a multiethnic city—at least at the time.

An Impossible Friendship is a remarkable account of a friendship that burned brightly for several years but could not withstand the political strife that tore apart the city that had nurtured that friendship. The author describes that the purpose of her book is to “set out not only to excavate and reimagine past everyday lives and dreams but also to envision alternatives to the impasse of identity politics both past and present.”3 By studying the trajectories of five individuals who were friends at a moment of great change, the author hopes to arrive at “a multidimensional narrative that would reproduce all of Jerusalem’s ambiguity and the overlapping traditions it represents, instead of reducing the complexity of the city’s history to a single dimension.”4 Drawing on interviews, archival records, correspondence, autobiographical sources, and other historical documents, she provides the history of the times in which these characters lived and developed their bonds. In the process, she creates an account of the complex times in which such a friendship was possible, but also impossible to maintain in the long run.

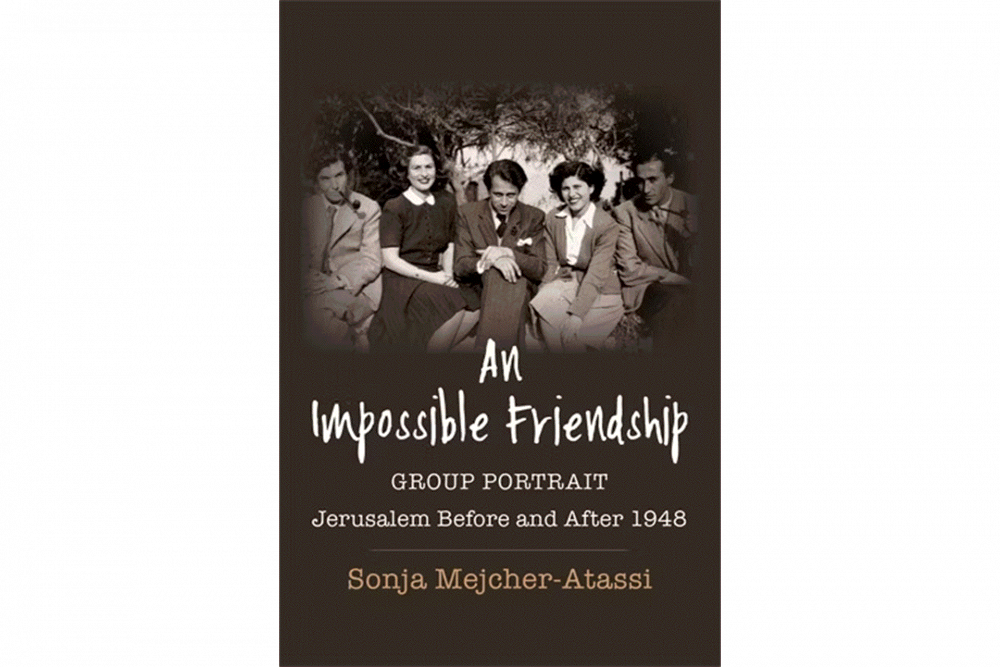

A photograph of the attractive bunch of friends graces the book jacket. Walid Khalidi, a Jerusalemite hailing from one of the city’s notable Muslim families, was a 21-year-old graduate of the University of London with a degree in English literature and a job at the Arab Office, working under Albert Hourani and compiling material for the report submitted to the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry. His wife, 24-year-old Rasha Salam, came from an eminent Lebanese political family that was known to promote Arab nationalism and women’s rights and produced political leaders such as Rasha’s brother, Saeb Salam, who served as prime minister and defense minister of Lebanon multiple times. Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, born in Adana to Syriac Orthodox parents who settled in Palestine in the 1920s, was then a 27-year-old graduate of Exeter and Cambridge; 26-year-old Sally Kassab was born in Beirut; and Wolfgang Hildesheimer (hereafter Wolf) was a German Jew whose family immigrated to Palestine when the Nazis came to power in 1933—he was 17 years old.

Following the Nakba, which fragmented Palestine and the friendship, Walid would go on to study history and make a name for himself as the author of many essential histories of the Nakba5 and the founder of the Institute for Palestine Studies; Jabra would become a novelist whose stature extended across the Arab world and an influential figure in the cultural scene in Iraq, which became his home when Palestine became off limits to him after 1948; and Wolf would become a playwright, novelist, and biographer in Germany. Wolf’s papers were archived, and they include his correspondence with Rasha over the years (and ending in 1988), and his illustrations for the work of Jabra. Almost nothing is known about the friendly, outgoing Kassab, who married a British diplomat and faded from view. She died in 1998. What we know about Rasha comes from her unpublished memoir, to which the author had access.

What brought them together in Jerusalem of the 1940s? The author’s explanation is worth quoting here:

what brought the ecumenical circle together and made their friendship possible was beyond wars but, paradoxically, also because of them. Despite a diversity in terms of religious background, the young men and women who made up this group of friends were a rather homogeneous group, differences in their individual social backgrounds notwithstanding. Partaking as they did in a cosmopolitanism of affluence, facilitated by English as their lingua franca, they were part of the British educated elite and had accumulated significant social, cultural, and economic capital. Although the Arab members were subject to colonial subjugation . . . their social habitus set them apart . . . from their fellow Palestinian Arabs, who did not have access to similar educational opportunities. This disconnect from the daily lives and worries of their fellow citizens may have been one of the profoundest tragedies of their lives, as their lifestyles and tastes . . . aligned them closely with their British friends in the hotel bar as “the years of fragile tranquility” in Jerusalem came to an end.6

One gets the sense that they were very earnest, these young adults ranging in age from 21 to 30, getting together to listen to and discuss a recording of T. S. Eliot’s “The Wasteland,” written when World War I had barely drawn to a close. These friends were young and educated, and cultural events appealed to them, as did intellectual pursuits generally. They and others in their circles represented the primary audience for the cultural programs of Jerusalem’s prestigious YMCA.

The author devotes a chapter to each of four of the friends. She begins with Walid Khalidi, born in Jerusalem to a family that could trace its roots in the city to the seventh century. He grew up in the neighborhoods of Bab al-Zahira and Jabal Mukabbir. Being born into an affluent family meant that his education was deliberately charted, and he moved in circles that afforded opportunities. His education included stints at the Quaker school in Ramallah and the Anglican St. George’s School in Jerusalem, in addition to private tutoring in history and literature from two instructors at Jerusalem’s Arab College, where his father served as principal from 1925 to 1948. The author traces Walid’s influences, which include his father, one of the most respected educators in the country, his stepmother, a prominent activist in the women’s movement, and his paternal grandfather, who talked to him about Arab and Islamic thought.

Walid dates the beginning of his political awareness to the Great Palestinian Revolt, which shook Palestine in 1936 when he was 12 years old. His uncle was among many political leaders banished by British Mandate forces to the Seychelles, and he recalled to the author watching as British soldiers chained a Palestinian villager to the front of a train to deter rebels from attacking it. The use of human shields has a long history in Palestine. In 1938, he recalled decades later, he and his family were forced out of their home one morning by armed British soldiers; they were still in their pajamas, and it took the intervention of a British family friend to resolve the situation.

Walid next dates his friendship with Jabra and Wolf to 1943, when he was 18 years old. By then, Jabra was a university graduate, and Wolf was working for the Public Information Office and publishing his own writing in the publication he edited, Forum. Walid published his own poems and translations there, too, and Jabra spent time at the Khalidi home, reading drafts of his work in progress to his two friends. Walid met Wolf’s Jewish friends who moved in literary and music circles, including Max Brod, biographer and literary executor of Franz Kafka.

Walid and Rasha left Jerusalem the day of the King David Hotel bombing and moved to Beirut, where Walid began working for the US legation, a regional headquarters for US agencies, hoping to influence American policy on Palestine. He also taught English at Makassed School and wrote articles for Lebanese newspapers.

Throughout 1948, Walid worked as personal secretary for his uncle, Hussein Fakhri al-Khalidi, general secretary of the Arab Higher Committee, who later became custodian of al-Haram al-Sharif when it came under Jordanian rule. In the spring of 1948, his father opened the Arab College to refugee families and placed it under the protection of the Red Cross delegation, and then he and his family left Jerusalem. But the property came under shelling from its immediate neighbor, the Jewish Agricultural School, and anyone who remained on the property was forcibly removed. That branch of the Khalidi family lived in exile after the Nakba. From then on, the loss of Palestine would be the focus of Walid’s lifework. The marriage of Rasha and Walid added one more knot in the marital bonds between the Salams and Khalidis, who could point to a handful of marriages between their sons and daughters. Born to Salim Salam and Kulsum Barbir, Rasha was the youngest of 13 children. She was raised mostly by her older sister Anbara, who would exert a real influence on her in terms of liberal attitudes and interest in feminism. In fact, Anbara created a sensation in Beirut in the late 1920s by removing her face veil in public.

The Salams were a political family in their own right, and their connections to Palestine went beyond their marriages into a prominent Jerusalem family. Salim Salam worked for a company that held the concession to drain the Huleh Valley marshland in northern Palestine. With the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, the concession became subject to legal disputes. Eventually, the Salams were forced to give it up, and the British Mandate turned the property over to a company founded by the Zionist Organization. The issue was politically sensitive—so much so that years later, Salim’s son wrote a book about it in an effort to lay to rest charges that the family had sold Palestinian land to Zionists.

In her unpublished memoirs, Rasha refers to her love of Jerusalem, which began to develop at an early age when she visited Anbara there after the latter married Walid’s father and became his second wife: “From the very beginning, Jerusalem exercised a bewitching, hypnotic effect on me . . . No other city in the world, not Venice, not my beloved Beirut of the old days, ever had that effect. There was a mystique about Jerusalem . . . Jerusalem was joy.”7 It is noteworthy that Rasha was able to compare Jerusalem to other cities she had visited. In the late 1930s and 1940s, people with means traveled for leisure. She attended the King Fuad I University in Cairo, where she lived and studied alongside other elite women from a range of Arab countries, all of whom seemed intent on changing their lives and breaking out of traditional social roles. But she did not graduate from the university; she left to marry Walid in 1945.

With marriage, she met her husband’s friends Jabra and Wolf. The four socialized frequently and soon became inseparable, finding it easy to talk to one another about intellectual as well as personal matters. At times, she would meet Wolf for coffee without her husband, a behavior not typical of newly married women, certainly not in 1945. Writing in her memoir about that period decades later, she describes her attraction to him and muses about the chance that she might have married him; she appeared to give weight to the intellectual and physical attraction between them, which was strong, and his being Jewish would not have stood in her way had she wanted to pursue that possibility. Her ability to imagine another life she might have lived and to acknowledge complications that she was sure she could overcome reflect the times for women in her socioeconomic class; she was clearly influenced by the feminist movement through the activism of her older sister, which opened possibilities of breaking out of traditional roles and norms. Her ability to not feel constrained by the political tensions wracking her adopted city seems a little harder to explain, but then, she was living in a Jerusalem undergoing transformation.

Jabra is introduced as “one of the last men of the Nahda,” and also as the “‘spark-plug’ of the YMCA Arts Club.”8 Born at the end of World War I in French-occupied Adana, his family’s history is reflective of the population upheavals that took place across the region throughout and after the war. In the early 1920s, when Jabra was an infant, his family fled the Assyrian genocide, during which Ottoman forces massacred and deported Assyrian Christians, and settled in Bethlehem. He grew up poor, but his intellectual prowess drew early attention and he was awarded scholarships to attend government schools in Bethlehem and Jerusalem and hand-picked by Ahmad Sameh al-Khalidi to receive a scholarship to study at Cambridge in the UK,9 where he earned his bachelor’s degree in 1943. He then returned to teach at the Rashidiyya school in Jerusalem, which he had attended and where he was taught and mentored by poet Ibrahim Tuqan.10 He met Walid during that period.

Jabra immersed himself in translation work, which he published in the Cairo-based cultural journal al-Hilal. The author tells us: “Jabra shared [Taha] Hussein’s admiration of western culture; at the same time, he embraced Arab nationalism, as promoted by [Sati‘] al-Husri, based on linguistic ties and cutting across regional as well as religious difference.”11 He was writing his own poetry and prose and working on his paintings during this time. He also founded the Arts Club at the YMCA, which sponsored lectures, poetry readings, art exhibits, and music recitals. It was at one of these events that Jabra and Wolf most likely met, although Walid’s father had known Jabra for many years at that point. The author identifies what they had in common: Both were members of minority communities that had experienced persecution elsewhere; they were educated in secular and progressive schools; and they shared interest in English literature, avant-garde art, and classical music. In fact, Wolf drew illustrations to accompany some of Jabra’s poetry.

In January 1948, the Haganah bombed the Semiramis Hotel in the New City. As a result, Jabra and his family left their home in Qatamon (like all other Palestinians in that neighborhood and the rest of the New City; see The West Side Story) and moved back to Bethlehem—temporarily, they thought, as did so many others. The bombing actually “contributed significantly to the flight of Qatamon’s predominantly Christian community.”12 That summer, Jabra left for Syria in search of a job; Iraq was hiring teachers, and so he headed there.

Wolf stands out as an enigma. A German Jew who lived in London and the Netherlands before moving to Palestine with his family in 1933, he considered himself a cosmopolitan European. His father came from a long line of Orthodox Jews, and his parents considered themselves Zionists who hoped to see Palestine become a binational state, but they did not try to influence their son politically. The family settled in Rehavia, a German Jewish colony that bordered Talbiyya in Jerusalem’s New City. In due course, they received Palestinian citizenship issued by the British Mandate.

Wolf left for London to study theater in 1937 and stayed until 1939. While there, he met members of the Palestinian community, some of whom were there for the Palestine Conference, which resulted in the White Paper. He was unsympathetic to the Palestinians; he wrote in 1939: “It seems to me that the Arabs are making unbelievable demands and are getting more outrageous. Here, however . . . it does not matter”13 because no one is listening to them anyway. Considering that the Palestinians in attendance at the conference were making the same demands about the future of their country they had been making since 1918, it is noticeable that this European should take such a condescending view, and his endorsement of the arbiter’s dismissal of their views smacks of racism and Zionist settler colonialism. His views, as presented through the letters he wrote, show no surprise that Westerners should be deciding the fate of an indigenous population. The author notes in passing that his view is consistent with his father’s Zionist leanings.

He returned to Palestine in 1939 and gradually kept a distance from the German Zionist community, opting instead for Jerusalem and the British community, through which he began to interact with Palestinian intellectuals. He opened an advertising agency and worked as a commercial artist; he also found work designing stage sets and costumes. By 1943, he was working for the Public Information Office of the British Mandate and told his parents that his work was compatible with the interests of the Yishuv. He also curated exhibitions at the YMCA, and the author posits that he might have met Jabra and Walid through those activities, which dates the friendship to 1943.

By 1943, Wolf and Sally Kassab were dating. The author was unable to uncover sufficient information about her, unlike the other friends in the ecumenical circle; Sally appears only in connection with Wolf and, after 1948, is reportedly in Cairo, where she fades from view.

Did the friends discuss politics? Oddly, it was not the focus of their conversations during this time of unrest. Walid recalls Wolf warning him that the Zionists were serious about their goals, which suggests that the Palestinians he knew were not as concerned as they should have been. In describing this period, Wolf recalls that his friends were Arabs and that their world vision was cosmopolitan and open-minded, unlike the Jews, whom he preferred to avoid. It is more than a little surprising that, in interviews he gave and in his correspondence during this time, he never mentioned the 1946 bombing of the King David Hotel, which is where much of the socializing of this class took place.

He left Jerusalem before the bombing, which means that recollections that he attended the Khalidis’ anniversary celebration were erroneous. When the State of Israel was announced in May 1948, he wrote to congratulate his parents and expressed a certain pride in the army. He reflects on his friends’ dismay; as presented, he doesn’t seem to have thought very much about the implications of that state on his friends’ lives or how they would live in exile. Over time, the author claims, he had a sense of disillusionment with Israel. And although he qualified for Israeli citizenship as a Jew upon the dissolution of the British Mandate for Palestine, he never applied.

After 1948, the friends had minimal contact. Jabra never saw the Khalidis again, though he remained in touch with Walid’s sister Sulafa in Beirut; he seems to have briefly corresponded with Wolf in the early 1950s. Sally Kassab was not seen or heard from by any of the friends, but when she died in 1998, she had a copy of Wolf’s obituary and his biography of Mozart. Wolf and the Khalidis met again in 1951 in England, and according to Wolf, were able to reestablish an instant connection.

But the memories of their conversation differ: Wolf and Walid reported that they didn’t discuss politics, whereas Rasha claims that they did and that Wolf opposed the establishment of Israel. Their last visit was in 1955. A relative recalled that the relationship frayed because Wolf was not as clearly anti-Zionist as he had been in Palestine. One can understand how disappointed his old friends must have been by his failure to condemn the state that had expelled hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from their own country. But perhaps this was expected given Wolf’s ambivalence toward the Arabs, at least beyond his circle of friends. It is fair to conclude that the translation work Wolf did for the Nuremberg trials when he moved back to Europe from Palestine had something to do with his sympathy for Israel. When the 1967 War broke out, Wolf was unambiguously on the side of the victor.

But that seemed to change over time, too. Rasha initiated a correspondence with Wolf in the 1980s as she was working on her memoirs and wanted help in recalling certain details, and her letters are part of his archived papers. Certain factoids emerge in their exchanges which suggest his disdain for Israel—in fact, one consistent trait in his life seemed to be his lack of any particular sense of affiliation to a nation-state. Walid gave him a copy of a book he had written, which Wolf gave to his sister. Perhaps he had read it or knew enough about it to think his Zionist sister might benefit from reading it; instead, she burned it in rage.

Both Rasha and Wolf seemed to realize that any desire to visit one another, to rekindle the old friendship that had existed among the group, might be a bad idea—that they might be better off holding on to their memories of a time when their friendship was strong, when they delighted in their comaradery, when they were moved by aesthetic ideas and fine music, and when they had their whole lives ahead of them to explore the world. Until the ground shifted and the world they knew disappeared, everything had seemed possible.

Notes

Sonja Mejchar-Atassi, An Impossible Friendship: Group Portrait Jerusalem before and after 1948 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2024), 10.

See, for example, Salim Tamari and Issam Nassar, eds., The Storyteller of Jerusalem: The Life and Times of Wasif Jawhariyyeh, 1904–1948 (Northampton, MA: Olive Branch Press, 2014); and Rochelle Davis, “Growing Up Palestinian in Jerusalem before 1948: Childhood Memories of Communal Life, Education, and Political Awareness,” in Jerusalem Interrupted: Modernity and Colonial Transformation, 1917–Present, ed. Lena Jayyusi (Northampton, MA: Olive Branch Press, 2015), 187–210.

Mejchar-Atassi, An Impossible Friendship, 11.

Rashid Khalidi, Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness, 2nd ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010), 18, quoted in Mejchar-Atassi, An Impossible Friendship, 20.

For example, Walid Khalidi, Before Their Diaspora: A Photographic History of the Palestinians 1876–1948 (Washington, DC: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1984); and Walid Khalidi, ed., All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948 (Washington, DC: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1992).

Mejchar-Atassi, An Impossible Friendship, 50 (emphasis in original).

Mejchar-Atassi, An Impossible Friendship, 88.

Mejchar-Atassi, An Impossible Friendship, 138.

Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, The First Well: A Bethlehem Boyhood, trans. Issa J. Boullata (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995), 185.

He received his master’s degree in absentia in October 1948. Mejchar-Atassi, An Impossible Friendship, 153.

Mejchar-Atassi, An Impossible Friendship, 151.

Mejchar-Atassi, An Impossible Friendship, 171.

Mejchar-Atassi, An Impossible Friendship, 116.