Jerusalem Gets a Luxury Hotel

Credit:

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [matpc 02581]

King David Hotel, a Focal Point in British Mandate Jerusalem Whose Bombing Was a Watershed Moment

Snapshot

The King David Hotel had been the administrative seat of the British Mandate when it was bombed by the Zionist group Irgun in July 1946 as part of a series of terrorist attacks that aimed to push the British out of Palestine as a first step in setting up a Jewish state. The explosion traumatized an already anxious population and contributed to the British decision to terminate the mandate and withdraw from Palestine less than two years later. The following day, the State of Israel was declared.

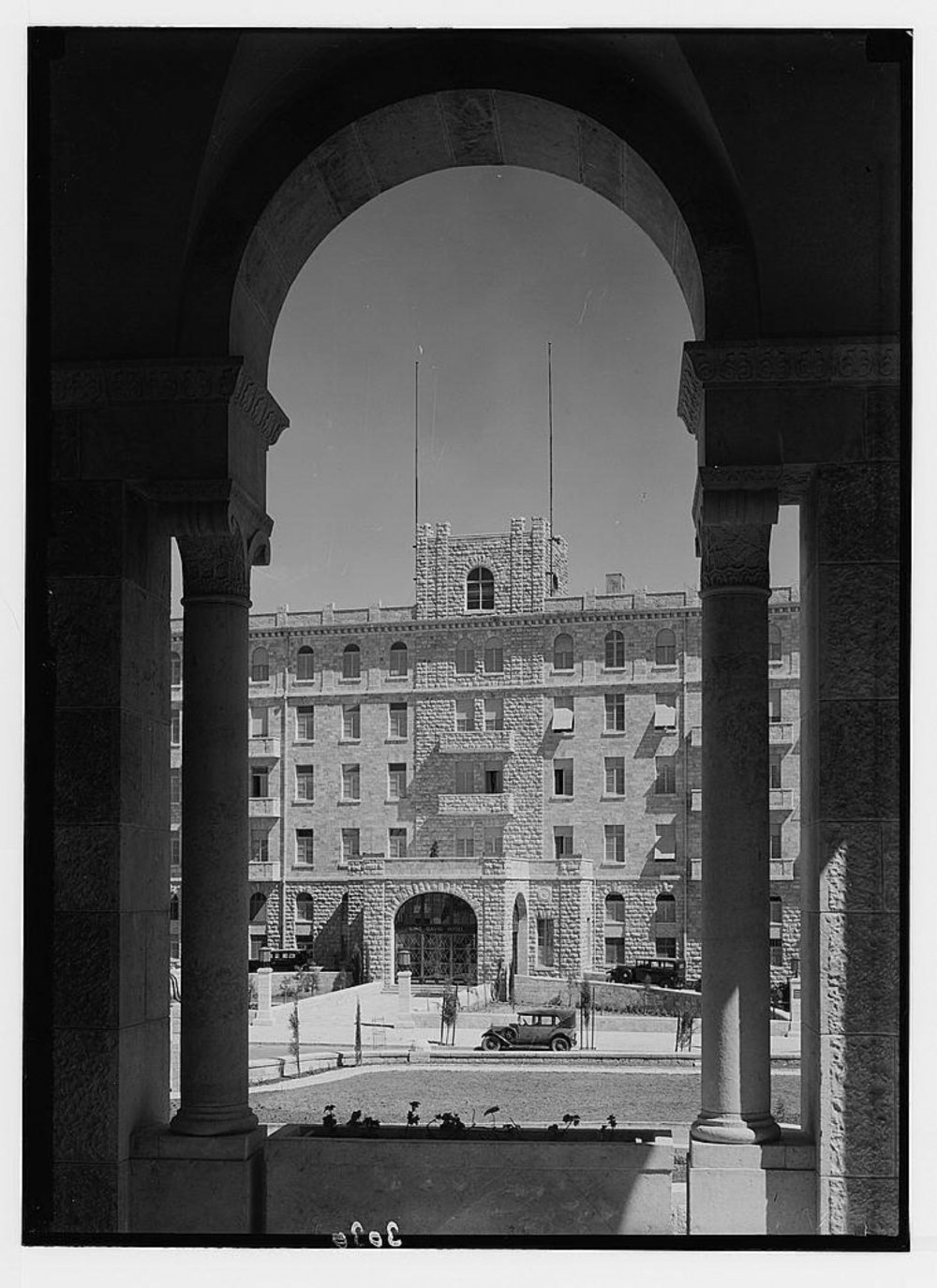

In 1929, a wealthy Egyptian Jewish banker named Ezra Mosseri bought a three-acre plot of land in the New City of Jerusalem from the Greek Orthodox Church with the intention of building a deluxe hotel. He named it the King David Hotel, and it opened its doors in 1931 as the city’s first luxury hotel.1

The chief architect was Emil Watt, who designed a six-floor plain yet elegant structure in the shape of the letter I, with a long axis connecting wings to the north and south. It was made from locally quarried pink limestone and had 200 rooms and 60 bathrooms.2

Watt’s approach was described by Hebrew University professor Ruth Kark:

[it was] typical of European architects who, commissioned to design buildings in Jerusalem, incorporated “Eastern-style domes, arches, various kinds of different-colored stone, and interior decorations with religious symbols and inscriptions,” in buildings whose strict symmetry marks them indelibly as European. The public rooms were decorated by G. G. Hufschmid in motifs taken from Assyrian, Hittite, Phoenician and Muslim buildings in an effort to evoke a “Biblical” style. Hufschmid, also Swiss, stated that his intention was “to evoke by reminiscence the ancient Semitic style and the ambiance of the glorious period of King David.”3

It had an international ambience, with its Swiss management, Italian chefs, and Sudanese waitresses.4 And it was a place in which “Briton, Jew, and Arab, along with a glittering array of visiting potentates, dignitaries, and the well-heeled, regularly congregated at its popular bar; dined and danced in its basement nightclub, La Regence; or took tea in the aptly named Grand Lobby.”5

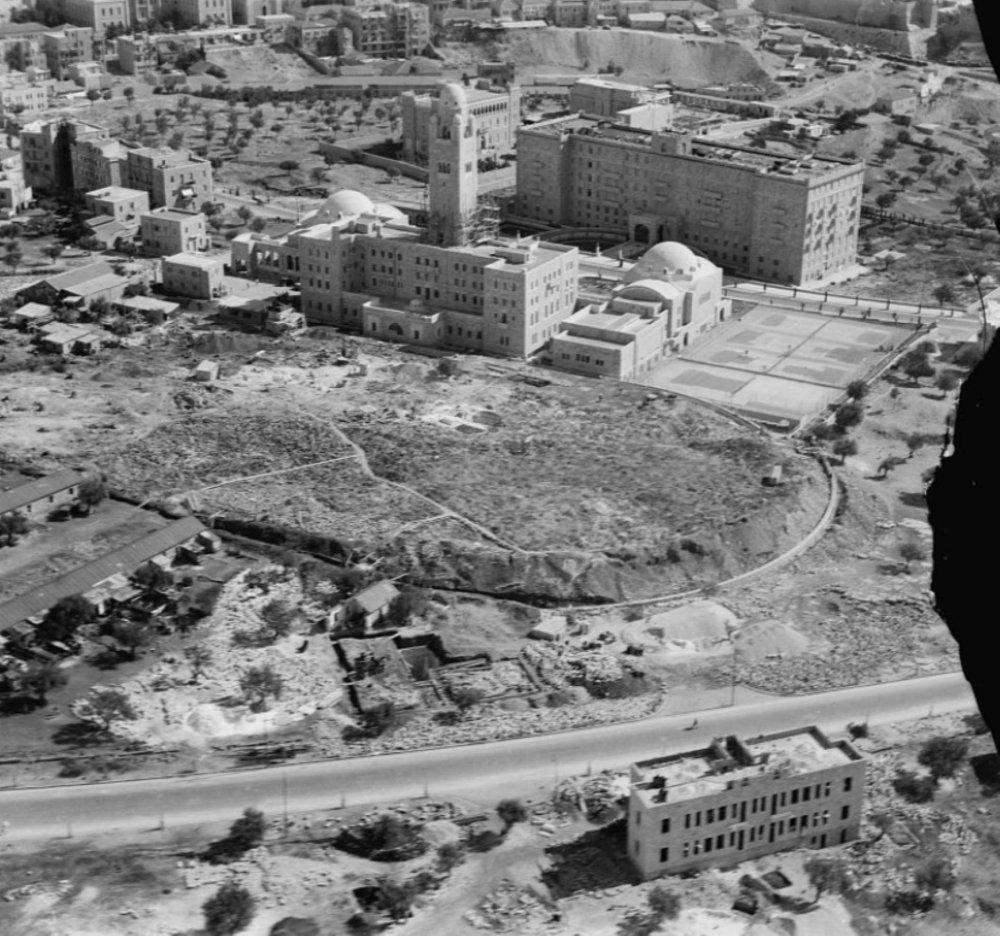

Several buildings were erected in Jerusalem around the same time as the hotel. Facing the hotel and on Julian Way (later to be renamed King David Street) was the International YMCA, which soon became a focal point for Jerusalem’s Palestinian middle class. Several cinemas, as well as the General Post Office and municipality offices, were in the vicinity, making it the central commercial area of the New City.6

Other additions to the Jerusalem landscape included the Government House, the Scottish Memorial Church, the Edison Theater, and the Sansur office building.

New construction was supposed to be consistent with the style of the existing architecture, but some people didn’t think that was the case with the hotel.7 Unlike the YMCA, whose architecture was described with admiration and delight in memoirs by Palestinian Jerusalemites, the hotel did not seem to generate that kind of enthusiasm when it was unveiled to the public.

In her biography of the Jerusalemite artist Sophie Halaby, American historian Laura Schor recounts the views of two British women who wrote about the new hotel. Helen Bentwich was a long-time resident of Jerusalem and part of the English elite. She held a dim view of the hotel, which she described as “a gigantic box, awaiting tourists”; the exterior “was too solid to be vulgar and too plain to be majestic.”8 Her view of the interior was more positive. As Schor described it,

Swiss interior decorator J. P. Hoffschmid had been asked to draw on the “ancient Semitic style” evocative of the time of King David. He designed a high-ceilinged, marble-floored lobby in muted beige and green colors, accented by Egyptian, Assyrian, Hittite, Phoenician, and Greek motifs in public areas. Food was dressed by waiters dressed in long white robes with broad red sashes, fezzes, and white gloves.

In Bentwich’s words, “The fleshpots of Egypt have at last been brought to Jerusalem, and it is no longer necessary to visit Cairo for an atmosphere of luxury and good food.”9

The other contemporary cited by Schor, Eunice Holliday, was married to Clifford Holliday, the architect of the Scottish Memorial Church, which was built around the same time. Her impressions of the hotel were decidedly more positive, Schor observed:

She noted that this hotel brought a new level of opulence and sophistication to the city. She described a supper dance at the hotel on New Year’s Eve: “It was a lovely place, much more luxurious and better run than anything Jerusalem has had before. The management was very lavish with et ceteras, and we were provided, in the course of the evening, with crackers (in abundance), squeakers, whistles, paper hats, balloons, rattles, streamers, little balls et cetera.”10

The Seat of the British Mandate Administration

By the mid-1930s, Palestine was in turmoil, and tourism to the Holy Land had declined. In 1936, the hotel leased two-thirds of its rooms (the southern wing) to the Colonial British Mandate administration as office space.11 It housed the mandate’s “military headquarters, intelligence stations, and government secretariat.”12 By the time World War II broke out, “more than two-thirds of the hotel’s rooms were being used for government and army purposes.”13

Between January 1944 and April 1947, Zionist militias launched a series of terrorist operations targeting the British Mandate, which they viewed as an obstacle in the way of establishing a Jewish state in Palestine. The most spectacular of those operations was the Irgun bombing of the King David Hotel on July 22, 1946.

The Bombing of the King David Hotel

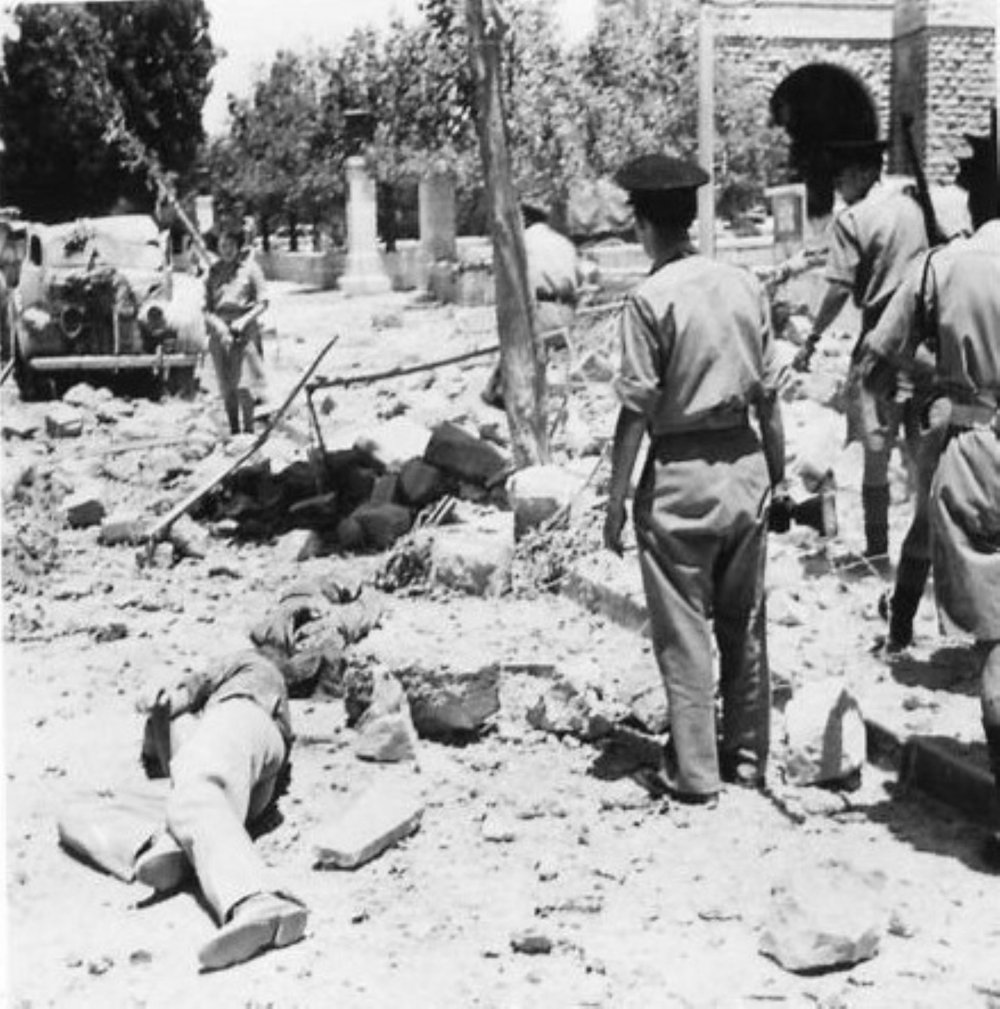

The Irgun operation is described by international relations professor Bruce Hoffman in an article, “The Bombing of the King David Hotel, July 1946.” In his account, the Irgun placed seven large milk churns holding 350 pounds of explosives in the basement nightclub, near pillars supporting the six floors. The terrorists were encountered by hotel staff when they entered and exited the hotel, and one British army officer was killed; others were confined to a room and kept under guard. Soon thereafter, a diversionary bomb was set off across the street. The bombs in the King David Hotel basement went off at 12:37 p.m., killing 91 and injuring 69 people.14

In his book Palestine Hijacked: How Zionism Forged an Apartheid State from River to Sea, historical researcher Thomas Suárez provides an exhaustive catalog of Zionist terrorist acts over the years, including attacks that resulted in a higher casualty figure than the 91 killed in the hotel bombing. Here is his summary of the King David Hotel bombing, what he calls the “iconic terror attack”:

Executed with the approval and cooperation of the Hagana, the attack was timed for when “the maximum number of people were in the building,” as a British report gloomily observed. It was “mass murder,” wrote Cunningham, “obliterating a complete cross-section of the public service:” the ninety-one dead included forty-one Palestinians (the British themselves using the word Palestinians rather than Arabs), twenty-eight British, seventeen Jews, two Armenians, one Russian, and one Egyptian. Sixty-nine people were injured.

British records describe how Irgun operatives disguised as Arabs entered the hotel and removed the reception clerk as other Irgun “Arabs” rounded up the remaining hotel employees in the basement . . . Security became aware of the intruders but, according to the British War Office, other Irgun “Arabs” then launched a diversionary bombing between the hotel and the YMCA and then fled in a saloon car. An Irgun Communique later called this a “warning bomb.”15

Among the dead and wounded were more than two-thirds of the Secretariat’s staff.16

Why was the hotel targeted?

The hotel was bombed during a period of heightened Zionist-British attacks. As a general goal, the Zionists wanted the British out of Palestine; the hotel was targeted because it was the administrative seat of the mandatory authorities. An additional motivation was that it was believed to store sensitive files that had fallen in the hands of the British Mandate authorities and which the Zionists wanted destroyed.

Were warning calls made to evacuate the hotel? A Haaretz account published on the 60th anniversary of the attack asserts that there were; it also claims that a British inquiry found that the warning didn’t reach anyone who could take action on the information.17 The article states that the British ambassador and consul-general insisted that no warning had ever been issued.18 Hoffman claims that a woman made calls to the hotel and two other locations to warn that the hotel had been rigged with timed explosives and to evacuate. He adds that conditions inside and outside the hotel were chaotic, resulting in the failure to pass the warning along to a person of authority.19

Suárez describes this claim of warning calls as a diversion; he finds it hard to believe that an operator would have remained in the hotel after receiving such a call, and a survivor who knew one of the operators was interviewed by Suárez and had heard of no such warning. Suárez suggests that this claim was developed by the Zionist movement in response to international condemnation of the attack. As events unfolded, it is likely that had the hotel been evacuated, the casualty count would have been higher due to flying shrapnel and glass.

A Seminal Event: Through the Lens of Memoir

The bombing shocked Jerusalem’s Palestinians and plunged the city in gloom. The British Mandate was considered a prestigious employer, and it employed many Palestinians as civil servants. The Jerusalem community was cohesive enough that most people knew someone who had been killed or injured by the attack. When interviewed about the incident more than 50 years later, Jerusalemite Edward Marroum described it as “akin to the psychological trauma induced by the terror attacks in the United States on September 11, 2001.”20

In memoirs that cover the 1940s, written decades after the bombing of the King David Hotel, the devastating event is very commonly referenced as a marker of the beginning of the fall of Jerusalem.

Issa Boullata writes in his memoir, Bells of Memory:

[Rohi Abdel Hadi] had a high position at the secretariat of the British mandatory government housed in the south wing of the King David Hotel, and was one of the few survivors saved from under the rubble several days after it was blown up on 22 July 1946 by members of the Zionist group Irgun, causing the death of ninety-one innocent persons—Arabs, Jews, and Britons.21

Nina Bazouzi Cullers writes in Living through the Nakba:

A relative of ours, Ibraheem Farraj, was among the dead. He was married to our daughter, Hana Ar‘a, and they had two young children.

The news of the blast and those killed was on everybody’s tongue. The death of Ibraheem Farraj brought a lot of grief to our home. My parents and relatives talked about nothing else for days. It was as if a blanket of grief, anger and worry was thrown over our otherwise tranquil life. Sorrow soon gave way to fear, a fear that gripped us and haunted our existence. Ibraheem and Hana and their two children about my age were not only relatives but good friends of ours . . .

A lot of people went by the site of the King David Hotel to see the destruction from the bomb. I recall going there with my parents. It was a horrible sight. I can’t believe that my parents let me see that. I could not imagine how bad it was for those innocent people who were blown up in the blast and buried in the rubble.22

Writing in her memoir, In Search of Fatima: A Palestinian Story, Jerusalemite Ghada Karmi similarly recalled the bombing as a pivotal turning point in the community’s history:

By the end of the day, the full story became clear. Jewish terrorists had blown up a whole wing of the hotel by posing as Arab delivery men and smuggling explosives hidden in milk cans into the basement. My father saw the fire and smoke from his office. He went out onto the balcony of the building and into a great cloud of dust which had drifted across from the site of the explosion. Nearly one hundred people, mostly Arabs but also British, and a small number of Jews, were killed. The dead included a number of our neighbours or acquaintances, since Jerusalem society was small and most families knew each other. “Poor Hilda,” my mother said. “Her poor, poor parents.” Hilda Azzam was a young secretary employed at the King David Hotel who was pretty and well thought of at work and my parents knew her family. She had perished in the explosion, as had Mr. Thompson, an English official who worked for the British authorities at the hotel and lived in the next street to ours. “Diabolical,” exclaimed old Mr. Jouzeh, our next door neighbour. “These people aren’t human. They’re devils from hell!”

All those who came to our house spoke of nothing else for what seemed like weeks. They said it took four days to dig out and move the bodies of the dead and wounded to the government hospital in the Russian Compound, right next to the maternity hospital where I was born. Those who were Jewish went to their own hospitals. There were funerals in Jerusalem for weeks afterwards, five or six a day, as some of the wounded joined the ranks of those who had died in the initial explosion. The social customs over bereavement, which were already elaborate in our society, became more so in the aftermath of these deaths. The women in our street, my mother amongst them, were all busy visiting the relatives of those who had died after the incident . . .

Nothing was the same after the King David incident.23

Zakia Hajjar describes the event in a letter to her daughter, included in the memoir In My Mother’s Footsteps:

We were at home when it happened. We heard the loud explosion and ran outside. We saw a huge cloud of smoke hanging over the city. We couldn’t believe what was going on. Then one neighbor called another neighbor, and that’s how we discovered it was the King David. We immediately thought of our friends as the YMCA was just across the street, and we were afraid that some of them might have been hurt, but no one at the YMCA was. About a hundred people perished and many more were injured in the King David bombing. For weeks, the city was in mourning. One of our friends, a woman my age, Hilda, was under the rubble for three days, calling out, “I’m Hilda Azzam. Please help me out.” Sadly, the rescuers were unable to get to her in time, and she perished alone and frightened under tons of limestone. Daily we attended more than one funeral, as every day more bodies were dragged out from the ruins. It was a terrible time, the beginning of the “changement,” you know, the change of our lives as Palestinians.24

Schor’s simple description helps show the effect of the losses—of people and familiar landmarks—on the city’s residents:

Among the dead was Nadia Wahbe, Sophie and Asia’s [Halaby] cousin. Nadia’s sisters, Sophie and Louba, were wounded. All three had worked for the British Mandate in offices at the King David. The explosion left a gaping hole in the hotel, a daily reminder of the bombing for all who stopped for coffee at the popular Piccadilly Café on Mamilla Road or visited the YMCA, directly across the street from the hotel.25

More than 50 years after the event, Jerusalemite John Tleel wrote:

The funerals of the King David Hotel victims still parade in front of my eyes. People were dug out of the debris days after the explosion, the corpses decomposing. We had to cover our noses when the funerals passed through.26

Wasif Jawhariyyeh, whose memoirs span the four-decade period 1904 to 1948 and provide a treasure trove of information about the life, history, and culture of Jerusalem during those years, described the aftermath of the bombing:

Jerusalem turned into a massive funeral. . . . As I write about this event, its painful memory makes my hands tremble, for my house was situated to the east of King David Hotel. So, we listened with sadness to the engine sounds of the machines that the government sent to remove the rubble and retrieve the bodies of the victims. Some of the victims were still alive and screamed for help under the rubble, such as Atallah Mantura and his colleague Mr. Erason who was also under the rubble and survived by a miracle. This broke the hearts of his wife, sons, and daughters, and still does to this day.

For a week, we lived on our nerves at our home in Nicoforia, watching every funeral go by from Jaffa Gate to Mount Zion Cemetery. Sadly, we could still smell the bodies of the victims at night, until they were all retrieved.27

By September 1947, the success of the Zionist strategy of terror was demonstrated when the British announced that they would terminate the mandate and turn Palestine’s fate over to the newly created United Nations.28 It did not repair the hotel.

During the 1948 War, the hotel was used by the International Committee of the Red Cross as a refuge for people who lost their homes. It was located on the 1949 Jordanian-Israeli armistice line. The hotel was sold in 1958 to the Israeli Dan Hotel chain.29

Notes

“The King David Hotel: Colonial Elegance, Turbulent History,” Danny the Digger, accessed April 12, 2024.

Some sources spell the architect’s name Emil Vogt. Wikipedia, s.v. “King David Hotel,” last modified April 12, 2024; Laura S. Schor, Sophie Halaby in Jerusalem: An Artist’s Life (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2019), 66.

“The King David Hotel,” Devex, accessed April 12, 2024.

“The King David Hotel,” Danny the Digger.

Bruce Hoffman, “The Bombing of the King David Hotel, July 1946,” 4, accessed April 12, 2024.

Salim Tamari, ed., Jerusalem 1948: The Arab Neighborhoods and Their Fate in the War, 2nd ed. (Jerusalem: Institute of Jerusalem Studies and Badil Resource Center, 2002), 57.

Schor, Sophie Halaby in Jerusalem, 65.

Schor, Sophie Halaby in Jerusalem, 66.

Schor, Sophie Halaby in Jerusalem, 66–67.

Schor, Sophie Halaby in Jerusalem, 66.

“The King David Hotel,” Danny the Digger.

Hoffman, “The Bombing of the King David Hotel, July 1946,” 1.

Religion Wiki, s.v. “King David Hotel Bombing,” accessed April 12, 2024.

Hoffman, “The Bombing of the King David Hotel, July 1946,” 7, 8, 10.

Thomas Suárez, Palestine Hijacked: How Zionism Forged an Apartheid State from River to Sea (Northampton, MA: Olive Branch Press), 155–56. The phrase “iconic terror attack” appears on page 157.

Hoffman, “The Bombing of the King David Hotel, July 1946,” 8.

David B. Green, “This Day in Jewish History: Irgun Blows Up British HQ at Jerusalem’s King David Hotel,” Haaretz, July 22, 2021.

Hoffman, “The Bombing of the King David Hotel, July 1946,” 2.

Hoffman, “The Bombing of the King David Hotel, July 1946,” 7, 8, 10, 13.

Rosemarie M. Esber, Under the Cover of War: The Zionist Expulsion of the Palestinians (Alexandria, VA: Arabicus Books & Media), 375.

Issa Boullata, The Bells of Memory: A Palestinian Boyhood in Jerusalem (Quebec: Linda Leith Publishing, 2015), 70–71.

Nina Bazouzi Cullers, Living through the Nakba: Tales of a Palestinian Youth (Harrisonburg, VA: self-pub., 2021), 87–88.

Ghada Karmi, In Search of Fatima: A Palestinian Story, 2nd ed. (London: Verso, 2009), 60–61.

Mona Hajjar Halaby, In My Mother’s Footsteps: A Palestinian Refugee Returns Home (London: Thread, 2021), 178.

Schor, Sophie Halaby in Jerusalem, 98.

John Tleel, “I Am Jerusalem: Life in the Old City from the Mandate Period to the Present,” Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 4 (1999): 34.

Salim Tamari and Issam Nassar, eds., The Storyteller of Jerusalem: The Life and Times of Wasif Jawhariyyeh, 1904–1948 (Northampton, MA: Olive Branch Press, 2014), 242.

“Zionist Operations against the British Mandate Authorities,” Interactive Encyclopedia of the Question of Palestine, accessed April 12, 2024.

“The King David Hotel,” Danny the Digger.