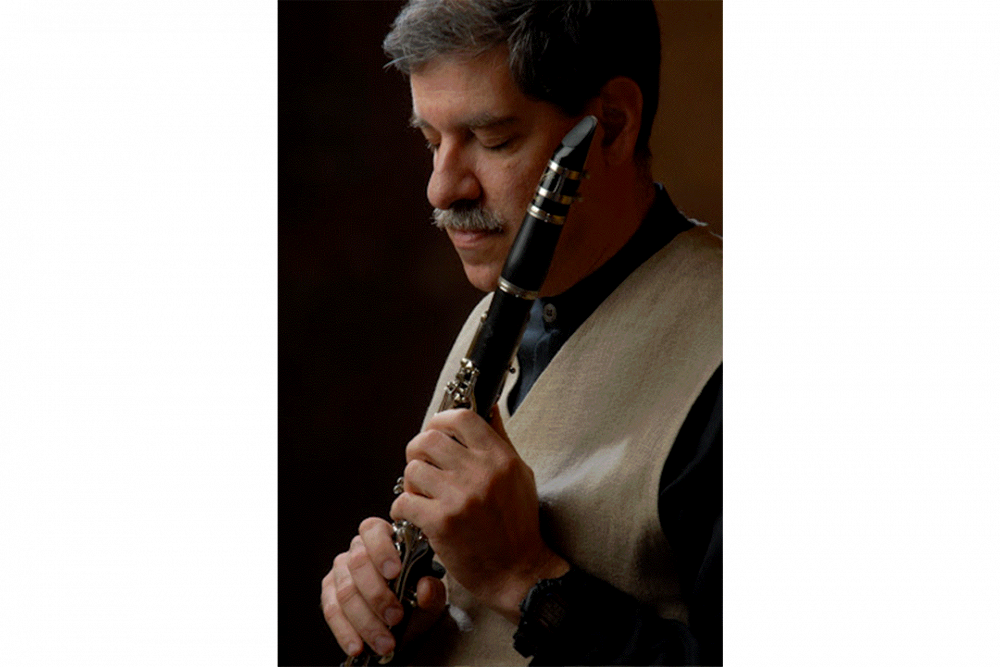

Suhail Khoury is a composer and a ney and clarinet player who has helped transform the musical and cultural landscape of Palestine generally and East Jerusalem in particular by building institutions that have instilled love and passion for music in every home, as well as national pride in Arab cultural heritage.

Early Years

Suhail Khoury was born in 1963 in Jerusalem, where he attended the Collège des Frères.

Khoury was raised in a family whose members were part of the cultural and social activism scene. His great aunt, Elizabeth Nasir, founded Jerusalem’s Rawdat El-Zuhur kindergarten. His mother, Samia Khoury, was president of the school for 17 years and is herself an educator and a social activist; she imparted to Khoury a passion for music and Palestinian culture.1

His aunt, Rima Tarazi, is a Palestinian composer, and his mother’s cousin, Sumaya Farhat Nasir, is a peace activist and writer.2 Another cousin, Kamal Nasir, was a poet.3 His great-aunt, Nabiha Nasir, founded a girls’ school in 1924 that would later become the West Bank’s prestigious Birzeit University.

Love of Music, Love of Country

Khoury grew up listening to classical music giants such as Beethoven and Mozart. At four years of age, he would stand in front of his mother’s gramophone and wave his hand with the music, as if conducting an orchestra.4 According to Samia, her son was practically addicted to Mozart’s Eine Kleine Nachtmusik. At the Collège des Frères, Khoury joined the school band, Rainless Reindeers, as the clarinet player.5

Alongside his love for music, Khoury was also brought up to love his country, serve its people, and value its freedom. There was no escaping the struggle engulfing his country: His cousin, the poet Kamal Nasir, had been assassinated by the Israelis in 1973, and his uncle Hanna Nasir, president of Birzeit University, had been deported in 1974 and lived in exile until April 1993, when he was one of 30 Palestinians Israel allowed to return during the Oslo negotiations.6 Love of country combined with passion for music and Jerusalem would inspire Khoury’s future activities and myriad contributions to Jerusalem.

Education and Musical Training

When Khoury was growing up, pursuing a career in music was regarded as something appropriate for wedding celebrations or folklore celebrations but not something one studied or turned into a career. He recalls, “If someone was carrying an oud on their back in the 70s and 80s, the boys on the street would make fun of them.”7

He studied Middle Eastern studies at Birzeit University and played the ney and clarinet for the university band. In the late 1970s, he also joined two bands in East Jerusalem: Friends of the Earth and al-Manar.

After that, his studies were more focused on music. He left for the United States and enrolled in the University of Iowa to study musicology and music performance from 1983 to 1985. Then he completed an MA in music at Kingston University in London.

Educator and Institution Builder

Khoury held several teaching positions. After completing his studies in the mid-1980s, he returned to Palestine and taught music at the Friends’ Girls’ School in Ramallah and the Hellen Keller School for the Visually Impaired in Jerusalem; he taught a ney course at Birzeit University that ran until 1987.

During this period, Khoury had a hand in establishing several musical groups, programs, and centers, all of which served to propel Palestinian musical heritage and culture into daily life. In all of his projects, Khoury seeks to promote music education and support young talent, lobbying for funding of musical programs, institutes, and cultural activities. In 1980, he co-founded the band Sabreen and served as its saxophone and ney player.8 This was still a time when the general attitude toward music as a career was unfavorable. According to Khoury, musicians were rarely paid, and concerts were funded by charities.9

Then in 1987, he cofounded the Palestinian Popular Art Center in al-Bira and served as its director.10 In 1989, he cofounded al-Funoun Palestinian Popular Dance Troupe, which he went on to direct until 1993. Also in 1993, he founded both the Palestine International Festival of Music and Dance, acting as its general director, and the National Conservatory for Music (NCM), now known as the Edward Said National Conservatory for Music (ESNCM). The ESNCM, the first music school in Palestine, has had a profoundly significant impact on Palestine’s music scene: It started with only 3 part-time teachers and 40 students. Now it serves about 2,000 students and has seven branches across Palestine, including in Ramallah, Jerusalem (in partnership with the Jerusalem Society for Music Education and Research), and Bethlehem—as well as outreach programs in refugee camps, UNRWA schools, and elsewhere.11

The core mission of the ESCNM is to “bring music to every Palestinian home.” The institution builds on a firm belief in “music as a form of national pride as well as a method of peaceful resistance.” Moreover the institution has invested both in preserving and developing Arabic musical heritage as well as developing skills and passionate commitment to classical Western music.12

The ESNCM works in three broad areas: education, outreach (bringing choirs and instrumental lessons to communities that don’t have any music training), and building cultural infrastructure. Under its aegis, in Jerusalem and beyond, numerous ensembles, chamber groups, orchestras, jazz bands, and music camps have sprouted and flourished, all of which have helped to ignite public interest in music and build audiences. Among these are the Palestine Youth Orchestra (PYO), the Palestine Strings (comprised of the string players of the PYO), the Palestine National Orchestra, and the Arabic Orchestra. The 70-instrument Arabic Orchestra was the first Arabic ensemble in the world with such a large number and specific combination of instruments. Conducted by Khoury, the Arabic Orchestra specializes in playing Arabic music, much of which is written specifically for it, even as it also performs pieces from Palestinian and Arab heritage that have been specially arranged for the orchestra. Thus, the Arabic Orchestra also creates extensive professional opportunities for others working in music, such as composers and arrangers, and technicians and professionals, including sound and lighting technicians, designers, and photographers, not to mention volunteers.13

In Jerusalem, the institute spearheaded Banat al-Quds, Daughters of Jerusalem, the all-female choir, established in 2013 and led by Khoury. The group includes 27 members who sing and play the flute, violin, bass, and qanun. They perform pieces by famous Arab composers, including music written by Khoury himself. One reviewer remarked, “Despite the oppression under which they live, these young women radiate in a powerful way joy, pride, hope and courage. Their songs are both a vision and a lament for the ancient city . . . . ‘Banat Al-Quds’ is an impressive choral album that sometimes sounds chilling, sometimes heartwarming.”14

“We teach children to love Beethoven, Mozart, Sibelius, Bizet, Rossini, Albeniz, and all of the great European and world classical composers,” Khoury says. “But we also teach the music of Abdul Wahab, Rahbanis, Said Darwish, and all of the great Palestinian and Arab composers of the 20th century.”15 Even more fundamental, the ESNCM teaches “tolerance, respect of the other, gender equality, freedom of speech, cultural exchange, and fundamental human rights.”16

A year after founding the NCM and until 1995, Khoury worked as the director of the Department for Music and Dance at the Palestinian Ministry of Culture. In 1995, he cofounded Yabous Cultural Centre in Jerusalem and started the band Washem. Yabous was established with the aim of supporting Palestinian artists, organizing musical events, and promoting Palestinian culture in the city.17

He cofounded and chaired the Palestinian Performing Arts Network (in 2015), was a member of the Oriental Music Ensemble, and served as president of the Forum of Arab Conservatories of Music, which is dedicated to creating a network of musicians and making music resources widely accessible.

Khoury currently serves as the general director of the ESCNM and is also a board member at Yabous Cultural Centre. As a leading figure of these institutions, he organizes cultural events throughout the year all over Palestine.

In Jerusalem, these have included the Layali al-Quds (Jerusalem Nights) festivals, carried out several times throughout the year, which include musical performances, plays, dances, and a display of crafts;18 and an annual month-long Arabic music festival called Layali al-Tarab fi Quds al-Arab (Nights of Tarab in Arab Jerusalem), which hosts musicians who perform and celebrate Arabic music.

Musical Compositions

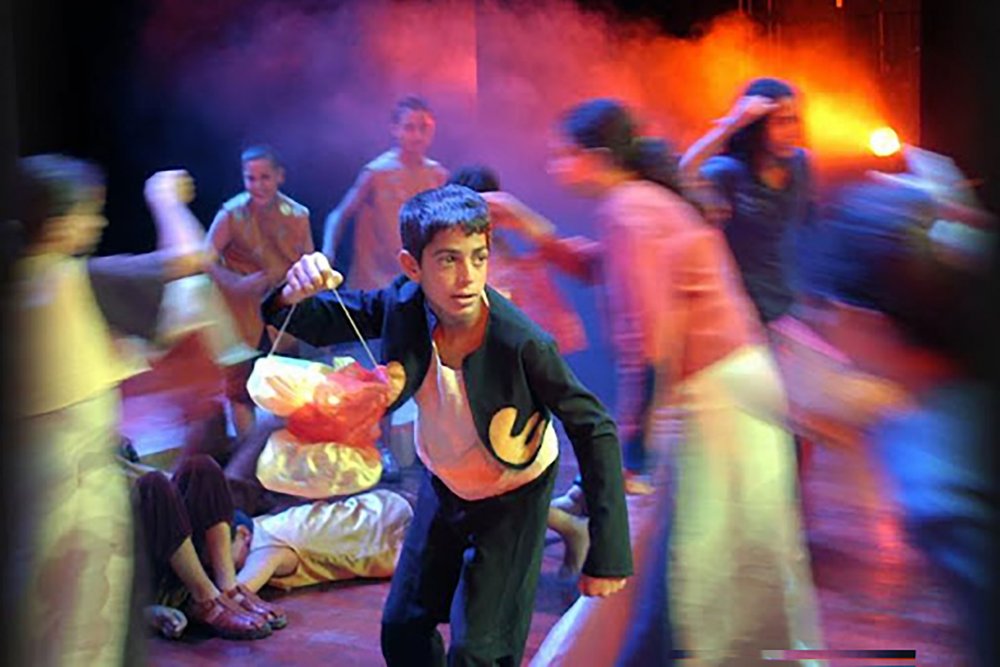

Khoury was also responsible for the gargantuan task of converting Ghassan Kanafani’s book al-Qandil al-Saghir into a musical entitled al-Fawanees (Lanterns). Kanafani wrote the book for the birthday of his beloved niece Lamees. The play tells the story of a princess who met the challenge given to her by her father to prove that she was worthy of inheriting his throne.

After the initial idea in the early 1990s of turning the book into a play failed to come to fruition, due to political circumstances prevailing at the time, it was Khoury who revived the project several years later. He composed the 28 songs for the play himself and launched its production. The cast included 60 children aged 8 to 15—selected after a rigorous process of auditioning 500 candidates from Jerusalem. More than 350 rehearsals later, the play was performed seven times over the course of two years.19

Khoury’s style brings together Arabic and Western instruments; it is simultaneously traditional and innovative. His records, from the first released in 1987, Marah, to al-Fawanees wa-l-Quds ba‘d muntasaf al-layl in 2009, exhibit a wide range of musical styles (see Discography, below).

Incarceration

In 1988, Khoury was imprisoned by Israel for copying music tapes. He relates:

One day, I was on my way back from the copy studio and secretly had in my possession about 6,000 tapes. The soldiers had been watching me for a long time, and the army set up a special ambush on the road. An ambush like this was usually only intended to capture a revolutionary leader. They arrested me as if I was a terrorist and what I had was a weapon.20

At the time, there was no law on the books they could use to convict him, so they used one from the Colonial British Mandate, sentencing him to 15 months in prison for “incitement to violence and revolution.” 21 During his incarceration, Israeli jailors severely tortured Khoury.22 What saw him through was the music he composed in his mind and later released.

As a result, Khoury produced an instrumental work, a collaboration with Karma’s Ahmad al-Khatib, that expresses his six-month experience as a prisoner in an Israeli jail. The words and music reflect the regular interrogation and torture he underwent, even naming some of the pieces after the specific methods used by the Israeli jailors.23 He released the collection, with arrangements by Ahmad al-Khatib, as a record called Jerusalem after Midnight in 2009.

The record isn’t all dark and gloom, however. Khoury also focuses on love and Jerusalem. Khoury believes that the Palestinian experience offers a unique sound and creates an altogether different kind of music industry: “Production companies in the rest of the Arab world are profit-oriented and favor creating superstars with easy hits that are indistinguishable from one another. Palestine can’t fit in this framework, we have a political cause and a wide variety of experiences, and our music reflects it.”24

Fight for Jerusalem

On the morning of July 22, 2020, Israeli forces broke into Khoury’s apartment and arrested him along with his wife, Rania Elias, who at the time was the director of the Yabous Cultural Centre. The arrest was unwarranted; seen within the context of Israel’s policies toward East Jerusalem, it was clearly aimed at staggering cultural life in Jerusalem and suppressing local Palestinian leadership in the city.25

Khoury strongly believes that the arrest was part of the systematized strategy to drain Jerusalem of anything that betokens hope, strength, courage, or love:

To only love Beethoven does not seem to bother the Israeli authorities. To only love your country also does not seem to bother them. Because if you love your occupied country and do nothing about it, there is no harm in that for them. If you act upon this love violently, Israel has a lot of experience of dehumanizing you and portraying you to the world as a terrorist. But to love your country and act on it by performing Beethoven seems to be dangerous, as the Israeli authorities have no prepared formula for how to deal with this “threat.” Suddenly, you become human in the eyes of the world, and Israel must hate that. How can anyone dehumanize a well-educated and talented generation of Palestinians? How can anyone condemn an 80 strong Palestine Youth Orchestra getting a standing ovation from about 2,000 Dutch spectators at the famous Concertgebouw in Amsterdam or a 4,000 strong Royal Albert Hall in London?26

The Edward Said Conservatory of Music was later accused of “promoting Palestinian culture,” to which Khoury proudly pleads guilty.

So how can they silence us? They have chosen to attempt to smear our reputation by using false evidence of money laundering, an outrageous and baseless accusation . . . That is why the attack was accompanied by an extremist Israeli media campaign to try to discredit the work of hundreds of artists and the music learning of thousands of children . . . The amateurish level of this Israeli news invention even failed to distinguish between Suhail Khoury, the Palestinian politician affiliated with the PFLP‡ residing somewhere in the Diaspora, and Suhail Khoury the composer and choral conductor from Jerusalem writing this letter to you.27

This wouldn’t be the end of the Israeli persecution of Khoury and his family: In October 2022, 12 armed Israeli military personnel broke into their house and arrested Khoury’s then-16-year-old son, Shadi. Shadi was dragged out of the house, blindfolded, his nose broken, and beaten to the point that his face became unrecognizable. He was imprisoned and interrogated (without the presence of a guardian or lawyer) for 40 days, all during which he was not permitted any contact with his family, save when he saw them briefly at court. After failed charges (of “drumming” on a vehicle of an Israeli citizen and disturbing the peace), Shadi was released but put under house arrest and forbidden from attending school.28 He is still under house arrest at the time of this writing.

A Shift in Social Attitudes

If Palestinians now regard a career in music as a serious and viable pursuit, and if the social attitudes toward musicians have changed, that is largely due to the efforts of figures such as Khoury. The institutions he founded, the initiatives he launched, and the organizations he served were fundamental to forming the Palestinian music industry and spreading music education. His life shows a passion for art and country rooted in a labor of love.

Reflecting on his imprisonment in the late 1980s, he writes:

People practice arts in every part of their life, clothes, food, tools, death . . . people sing while they reap the fields, pick the olives, fish in the sea, while the shepherd looks after his sheep. And in every particular struggle, art takes a role, expressing the situation, and artists, writers and poets take the lead.29

Discography

Marah [Joy], 1987

Marj Ben Amer, 1989

Ashiqa [Lover], 1995

Matar [Rain], 1998

Al-Fawanees [Lanterns], 2004

Jerusalem after Midnight, 2009

Sources

All4Palestine. “Suhail Khoury.” Accessed October 23, 2024.

Faces of Palestine. “Suhail Khoury.” Accessed October 23, 2024.

Hanieh, Shams. “PMC First Session: Meditations on the Palestinian Music Industry.” Jafra Productions (blog). Accessed October 23, 2024.

Husseini, Ibrahim. “Palestinian Child Prisoner Shadi Khoury Is Out of Prison, but Now under House Arrest,” New Arab, November 28, 2022.

“Jerusalem Nights Festival.” Edward Said National Conservatory of Music. Accessed October 23, 2024.

Khoury, Suhail. “Loving Beethoven and Your Country Seem to Be a Dangerous Combination.” PalMusicUK, July 30, 2020.

Khoury, Suhail. “A Victory Piece with a Contradiction.” The Cultural Intifada. Accessed October 23, 2024.

Lafferty, Zoe. “Dreams of Liberation: Israel’s Censorship of Palestinian Art.” New Arab, October 3, 2022.

Marianna, Cara. “In the Shade of an Olive Tree: A Grandmother Remembers al-Nakba.” Sheerpost, July 6, 2024.

“Mrs. Samia Khoury.” Birzeit University. Accessed October 23, 2024.

Parks, Michael. “Profile: Exiled Palestinian Comes in from the Cold: ‘This Is Where I Belong,’ Says University President Hanna Nasir, Home after 18 Years,” Los Angeles Times, May 25, 1993.

Womex. “Suhail Khoury.” Accessed October 23, 2024.

[Profile photo: Faces of Palestine]

Notes

“Mrs. Samia Khoury,” Birzeit University, accessed October 23, 2024.

Cara Marianna, “In the Shade of an Olive Tree: A Grandmother Remembers al-Nakba,” Sheerpost, July 6, 2024.

Marianna, “In the Shade of an Olive Tree.”

Suhail Khoury, “Loving Beethoven and Your Country Seem to Be a Dangerous Combination,” PalMusicUK, July 30, 2024.

PASSIA, “Suheil Khoury,” accessed October 23, 2024.

Michael Parks, “Profile: Exiled Palestinian Comes in from the Cold: ‘This Is Where I Belong,’ Says University President Hanna Nasir, Home after 18 Years,” Los Angeles Times, May 25, 1993.

Shams Hanieh, “PMC First Session: Meditations on the Palestinian Music Industry,” Jafra Productions (blog), accessed October 23, 2024.

PASSIA, “Suheil Khoury.”

Hanieh, “PMC First Session.”

All4Palestine, “Suhail Khoury,” accessed October 23, 2024.

Suhail Khoury, “A Palestinian Miracle: The National Conservatory of Music,” This Week in Palestine, no. 278 (2021).

Khoury, “A Palestinian Miracle.”

Suhail Khoury, “The Arabic Orchestra,” This Week in Palestine, no. 288 (2022).

“Jerusalem Nights Festival,” Edward Said National Conservatory of Music, accessed October 23, 2024.

Khoury, “Loving Beethoven.”

Khoury, “Loving Beethoven.”

All4Palestine, “Suhail Khoury.”

“Jerusalem Nights Festival.”

“Al Fawanees Musical,” Birzeit University, accessed November 3, 2024.

Zoe Lafferty, “Dreams of Liberation: Israel’s Censorship of Palestinian Art,” New Arab, October 3, 2022.

Lafferty, “Dreams of Liberation.”

Lafferty, “Dreams of Liberation.”

Womex, “Suhail Khoury,” accessed October 23, 2024.

Hanieh, “PMC First Session.”

The Israeli forces never gave a reason for the arrest, but rather accused the Edward Said National Conservatory of Music and the Yabous Cultural Centre of false crimes. Khoury himself guesses the reasons: “Other than the ongoing daily policies the Israelis are trying to enforce in East Jerusalem, we do not know what triggered the attack on the morning of the 22nd of July, on The Jerusalem Society for Music Education ‘Edward Said National Conservatory of Music’ and Yabous Cultural Center, two of the most prominent cultural institutions in Jerusalem . . . . Bishop Atallah believes such arrests are targeting Christian leadership in the city. Rania and I have considered the possible relationship with the court case underway for our family reunification†. The Israeli authorities are trying to deny us living together in Jerusalem even after 22 years of marriage. And there are several other theories, all of which might be true.” Khoury, “Loving Beethoven.”

Khoury, “Loving Beethoven.”

Khoury, “Loving Beethoven.”

Ibrahim Husseini, “Palestinian Child Prisoner Shadi Khoury Is Out of Prison, but Now under House Arrest,” New Arab, November 28, 2022.

Suhail Khoury, “A Victory Piece with a Contradiction,” The Cultural Intifada, accessed October 23, 2024.