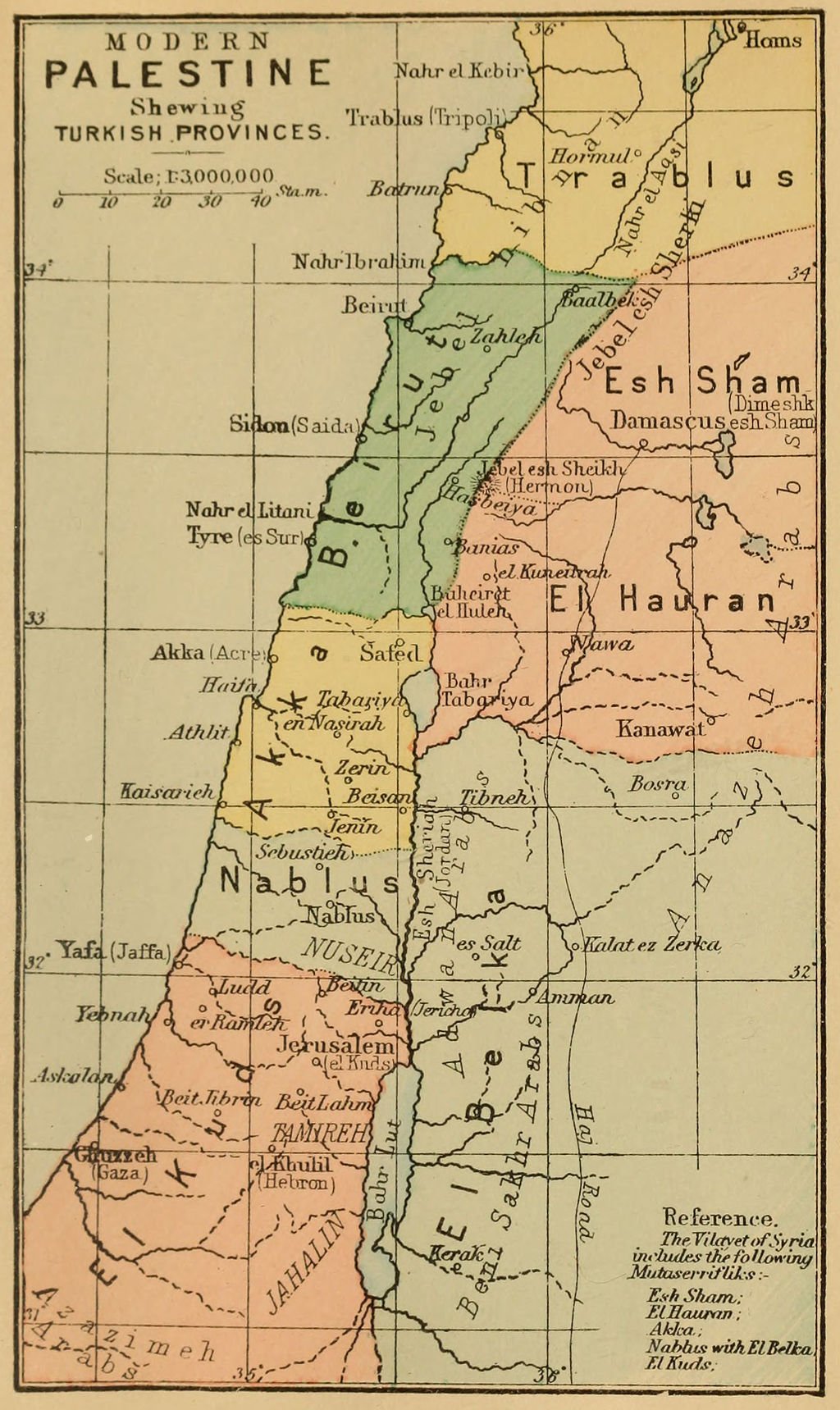

Jerusalem—al-Quds in Arabic—has existed for over 5,000 years within the mountainous region between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River. The word “Jerusalem” acquired multiple territorial meanings across the ages, a plurality of geographical designations contingent on local understandings of belonging to the city and its region. These meanings extend from the historical core of the Old City to as far north as Ramallah, as far south as Bethlehem, and as far east as Jericho.

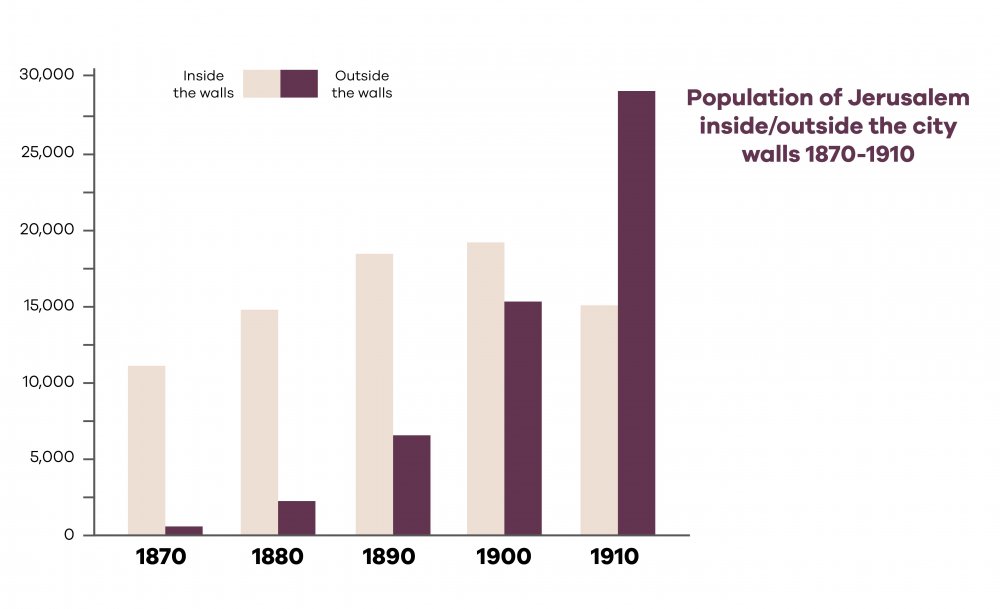

Over the course of its history, and especially since the late Ottoman period, the city of Jerusalem witnessed major expansions to its boundaries. Since the colonization of Palestine by the British in 1917, and later on with the establishment of the State of Israel, the city’s boundaries have shifted and expanded according to various political realities. In the past century, these shifts have mostly been imposed upon the indigenous community without its consent, to the point that today, there is no single agreed-upon definition of the city. Rather, there are multiple and competing boundaries and constructs unilaterally imposed or proposed, making even the very mention of “Jerusalem” a potential source of miscommunication and contention: Which Jerusalem do you mean?

The shifting and forced redefining of borders has had devastating consequences for the Palestinians of Jerusalem, who are forced to navigate among these overlapping multiple “Jerusalems” every waking moment.

For those who wish to know and understand this community and its story within the city, as well as the story of Jerusalem itself through this lens, the starting point is an overview of the complexities involved in even defining where Jerusalem is.

Here we invite you to explore the question, “Where is Jerusalem?”