Introduction

Credit:

Shutterstock

The Gates of the Old City

The seven gates to the Old City can sometimes feel like many more than that, because they go by different names in various languages. Even in one language, some gates have multiple names. But they are a fundamental reference point for Palestinian Jerusalemites, and therefore an important puzzle piece in our Topic, What Is Jerusalem?

Below is a quick guide for the perplexed.

Overview

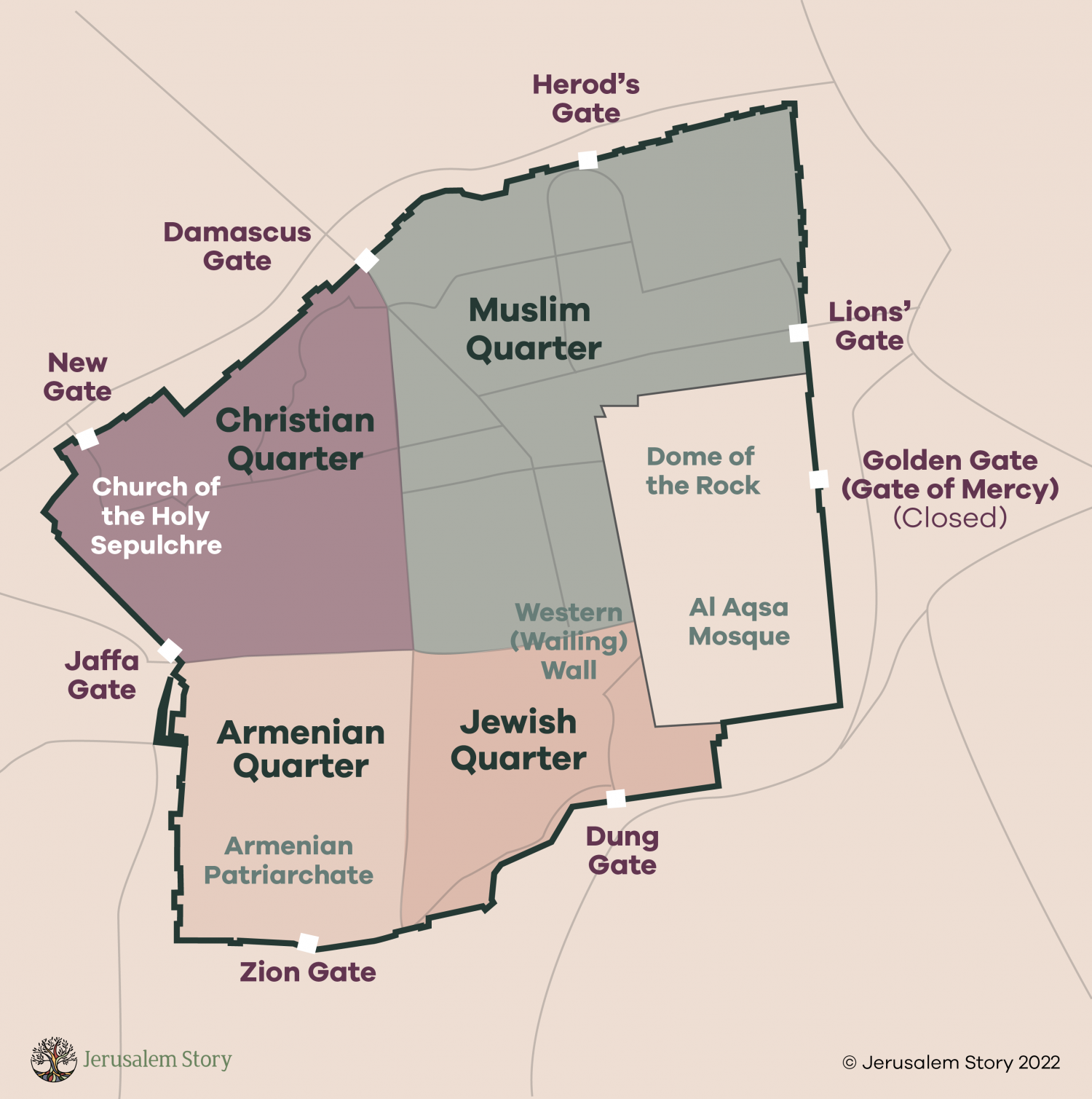

The Old City of Jerusalem, which covers about 0.9 square miles, is shaped like a quadrilateral with sides extending for 3,000 feet (900 meters).1 The gates are the portals or entry passages into the walled space.

The number of gates has varied over time. During the Crusader kingdom (1099–1291), there were four gates, one on each side. But from 1535 to 1542, the Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Magnificent restored and rebuilt the crumbling Old City walls to protect the city from a feared Crusader invasion. In the process, six gates were opened in the rebuilt wall.2 (A seventh gate was sealed, see below). Three centuries later, another gate was added, for a total (yet again) of seven.

Each gate is topped by openings in the wall, a medieval fortress feature enabling the release of “weapons” such as boiling liquids or stones to be aimed at the attackers below.

Damascus Gate/Bab al-Amud

On the northwest wall is the Damascus Gate/Bab al-Amud (built 1536–38), which Ottoman court architect Sinan is said to have personally designed.3 (It faced the Syrian capital, and the road leading out from it led to Damascus; hence the name in English.)

It is the largest and most magnificent of the gates, and it stands at the lowest geographic point in the Old City. It was built on the remains of a gate from Roman times (visible as a small arch to its lower left).

The Arabic name means Gate of the Pillar, which derives from the Roman and Byzantine period when a tall pillar stood in the middle of the plaza outside the original gate. This was a Roman victory column topped by the image of Emperor Hadrian.4 The pillar served as the zero point for measuring the distance between Jerusalem and other nearby cities.

Bab al-Amud is the only gate that retained its original name during the Ottoman reconstruction of the wall.5 This gate is also sometimes called Bab al-Nasr in Arabic (Gate of Victory).

It is the main gate Palestinians use to enter the Old City, and the plaza around the Damascus Gate is a central community touchpoint (see A Bab al-Amud Morning). Outside the gate is a road leading to Nablus. Entering the Old City through the gate, to the right is the Christian Quarter, and to the left is the Muslim Quarter.

Souq Khan al-Zeit (the olive oil market) is the liveliest part of the Old City, and it runs down the middle. Halfway down the main street is the Via Dolorosa.6

Herod’s Gate/Bab al-Zahra

Moving east, one reaches the smallish Herod’s Gate (Bab al-Zahra in Arabic, or Gate of Flowers), built 1537–38. Herod’s Gate leads to the neighborhoods of al-Sa‘diyya and Bab Hitta in the Muslim Quarter, and connects it to the Bab al-Zahra neighborhood outside the wall.

On the internal facade of the gate, decorative Islamic art motifs are visible.7 The Arabic name, Bab al-Zahra, refers to these motifs; the English name comes from European pilgrims who mistook the gate for a place associated with Herod Antipas; despite the error, the name stuck.8

Lions’ Gate/Bab al-Asbat

Rounding the corner and walking along the eastern wall of the Old City, one comes to the Lions’ Gate/Bab al-Asbat next to al-Ghazali Square. This ancient gate goes by many names. Another Arabic name, Bab Sittna Maryam (Gate of Our Lady Mary), refers to the gate’s proximity to the Hannah Church, where Christians believe the Virgin Mary was born.9 Coptic Christians refer to it as St. Stephen’s Gate after the legend that the first Christian martyr, Saint Stephen, was stoned to death outside this gate, although accounts vary. Jerusalemites call it Sheep Gate or Jericho Gate.10

Built in 1538–39,11 it leads directly to the Muslim Quarter and is the closest gate to al-Aqsa Mosque. This gate also serves as the main access point outward from the Old City to the two main Muslim cemeteries outside the walls, the northern Bab al-Rahma cemetery and the southern Yusufiyya cemetery. And heading inwards into the Old City, it is the main entrance through which Muslims enter the al-Aqsa compound to pray in the al-Aqsa Mosque.12

Carved into the wall above the gate are four lions, two on the left and two on the right. (One source claims that they are in fact leopards but are often mistaken for lions.)13 Sultan Suleiman “had the carving made to celebrate the Ottoman defeat of the Mamluks in 1517. Legend has it that Suleiman’s predecessor and father, Selim I, dreamed of lions that were going to eat him because of his plans to level the city. He was spared only after promising to protect the city by building a wall around it. This led to the lion becoming the heraldic symbol of Jerusalem.”14

In fact, however, the Lions’ Gate predates Ottoman times and is the only gate to the Old City that has been open since it was founded.

Golden Gate/Bab al-Dhahabi or Gate of Mercy/Bab al-Rahma (Closed)

Not far along from the Lions’ Gate on the eastern side of the wall lies a gate dating from the sixth century, known variously as the Golden Gate (Bab al-Dhahabi), or the Gate of Mercy (Bab al-Rahma). This gate is believed by Muslims and Christians to be the last gate Jesus used to enter Jerusalem en route to his crucifiction, and by Jews to be the gate through which the Messiah will enter Jerusalem (whereupon it will magically open). Muslims also believe this is the gate through which the just will pass on the Day of Judgment.

This gate was was sealed in 1541 by Suleiman during the wall restoration.15

Outside the wall at this gate is the large Muslim cemetery called Bab al-Rahma cemetery. The Yusufiyya cemetery is an extension of it.

Dung Gate/Bab al-Maghariba

The southeast end of the Old City is accessed through the Dung Gate (also called Silwan Gate, since it faces the Palestinian neighborhood (formerly village) of SIlwan to the city’s south, or in Arabic, Bab al-Maghariba [The Moroccan Gate or Gate of the Moors]). Considered the back door of the Old City, this gate, built 1540–41, provided access to the Old City’s Jewish and Maghariba (Moroccan) Quarters; the latter was destroyed within days of the 1967 War to enlarge the Jewish Quarter.

The label “Dung Gate” might have come from the translation of a Hebrew word for garbage; in days long gone, people tossed their garbage through this gate to the Valley of Hinnon to be burned.16

The Dung Gate is the main passageway for vehicles coming out of the Old City and for buses going to the Western Wall, which lies to the right just inside the gate. Also inside the gate is the Jerusalem Archeological Park, also known as the Ophel Garden, which has “open-air exhibits of archeological and architectural finds from all eras of Jerusalem [that] include the remains of some previously unrecognized early Islamic edifices.”17

Zion Gate/Bab Haret al-Yahud

Zion Gate/Bab Haret al-Yahud (Arabic for the Gate of the Jews’ Quarter), built in 1540, is located in the southwestern part of the wall. It is also called in Arabic Bab al-Nabi Da’ud (Gate of the Prophet David). Leaving the city, Zion Gate provides access to Mount Zion; entering the city, Zion Gate leads straight into the Armenian Quarter. The gate is high and large compared to other gates.

In the second half of the 19th century, a leper colony, livestock market, and slaughterhouse were located near the gate.18

As seen here, it still bears the visible scars of the 1948 War, when the Palmach forces dynamited it during their failed attempts to conquer the Old City and liberate the besieged Jews who were trapped in the Jewish Quarter.19 Ultimately they retreated and the Old City remained on the Jordanian side of the city until the 1967 War.

Jaffa Gate/Bab al-Khalil

Jaffa Gate (also called Hebron Gate, which is its Arabic name Bab al-Khalil [also meaning Gate of the Friend]), built in 1538, the second largest of the gates, is located in the middle of the Western Wall of the city and faces Bethlehem and Hebron to the south and Jaffa to the west. Hence, its various names. The road leading westward away from this gate and the city led to Jaffa, a major port city; hence its name, Jaffa Road.

In Arabic, this gate is also sometimes called Bab Mihrab Da’ud (Gate of the Prayer Niche of David). The Tower of David, an ancient citadel first built in the second century, stands nearby.

Dignitaries and conquerors alike used this gate. But so did people arriving by horse carriage, bus, or railway; the gate was conveniently located near transportation hubs. When the railroad was built in the early 20th century, this route became a major one for pilgrims visiting the Holy City. In the second half of the 19th century, catering to this traffic, a host of services—markets, hotels, coffee shops, photography shops, other businesses—was located just outside Jaffa Gate.

Inside Jaffa Gate was the citadel, from where the governor of Jerusalem ruled. Entering the gate, the Armenian Quarter lies to the right and the Christian Quarter to the left; the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is nearby.20

In 1898, the low-lying section of wall next to Jaffa Gate was opened, that section of the Crusader moat was filled, and a road was paved to allow the entourage of the visiting German emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II, to enter the city comfortably and in style.21

In 1907, a 25-meter high clock tower of white limestone was built atop the gate, on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of Sultan Abdul Hamid II’s accension to power.22 However, the British later dismantled it (see The West Side Story, Part 1: Jerusalem before “East” and “West”).

In 1917, this was the gate through which the conquering British army entered the city and declared its military occupation of it (see General Allenby's Entry into Jerusalem in 1917).

In 1948, the Haganah fought hard to try and take this gate, which would have connected the Old City and the Jewish Quarter therein to the western side of the city that they held, but they failed. This gate remained in the Jordanian-held side of the city until 1967.

New Gate/Bab al-Jadid

A gate on the northwestern side, the New Gate (Bab al-Jadid), was opened in 1889 to create access between the Christian Quarter and new neighborhoods being established beyond the Old City walls. It was built in 1887, during the rule of Ottoman sultan Abdul Hamid II and with his permission, at the request of European powers and Christian institutions, to make it easier to access the burgeoning New City neighborhoods just outside the walls, such as Musrara, from the Christian Quarter; the New Gate was intended to reduce traffic at the other gates.

The Notre Dame de France, the most prominent Catholic landmark in the city, is across the street from this gate.23

The Gates of the Old City—Summary

| Primary English name | Primary Arabic name | Other English names | Other Arabic names | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Damascus Gate | Bab al-Amud | None | Bab al-Nasr (Gate of Victory) | Largest and most elaborate gate; only gate to retain its original name |

| Herod’s Gate | Bab al-Zahra | Gate of Flowers | None | |

| Lions’ Gate | Bab al-Asbat | St. Stephen’s Gate Sheep Gate |

Bab Sittna Mariam (Gate of Our Lady Mary) | |

| Gate of Mercy | Bab al-Rahma | Golden Gate | Bab al-Dhahabi | Gate that was closed in the sixth century but has religious significance to Muslims, Christians, and Jews |

| Dung Gate | Bab al-Maghariba | Moroccan Gate Gate of the Moors Silwan Gate |

None | “Back door” of the city; main passageway for vehicles exiting the Old City today |

| Zion Gate | Bab Haret al-Yahud | Gate of the Jews’ Quarter | Bab al-Nabi Da’ud (Gate of the Prophet David) | |

| Jaffa Gate | Bab al-Khalil | Hebron Gate | Bab Mihrab Da’ud (Gate of the Prayer Niche of David) | Second largest gate; gate historically used by visiting dignitaries; gate through which the British army entered the city in 1917 |

| New Gate | Bab al-Jadid | None | None | Newest and most recent gate; connected New City neighborhoods outside the wall to the Christian Quarter inside it |

Sources

Abu Sharar, Adam. “The Shop at Bab al-Khalil.” Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 15 (2002).

Armstrong, Karen. Jerusalem: One City, Three Faiths. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996.

Auld, Sylvia, and Robert Hillenbrand. Ottoman Jerusalem: The Living City, Part I (1517–1917). London: Altajir World of Islam Trust, 2000.

Bahat, Dan.The Illustrated Atlas of Jerusalem. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1989.

Büssow, Johann. Hamidian Jerusalem: Politics and Society in the District of Jerusalem, 1872–1908. Vol. 46 of The Ottoman Empire and Its Heritage: Politics, Society and Economy, edited by Suraiya Faroqhi, Halil Inalcik, and Bogac Ergene. Leiden: Brill, 2011.

“Dung Gate, Jerusalem.” GPS My City.

Encyclopedia Britannica. s.v. “Landscape of Jerusalem, City Layout.”

“Gates of Jerusalem.” Madain Project.

“Gates of the Old City.” Bible Places.

“Jerusalem Visitor Guide.” Bab al-Sahira (Herod’s Gate).

“Mapping Jerusalem’s Old City.” National Geographic.

“New Gate—Jerusalem.” Bible Walks.

Reuters Staff. “Portals to History and Conflict: The Gates of Jerusalem’s Old City.” Reuters, October 7, 2019.

Shahin, Mariam. Palestine: A Guide. Photography by George Azar. Northampton, MA: Interlink Books, 2005.

Wikipedia. s.v. “Gates of the Old City of Jerusalem.” Last modified October 24, 2021, 08:29.

Wikipedia. s.v. “Lions’ Gate.” Last modified November 24, 2021, 22:12.

Wikipedia. s.v. “Zion Gate.” Last modified November 3, 2021, 12:18.

Contributors

Ida Audeh and Kate Rouhana collaborated on this Photo Essay.

Notes

“Mapping Jerusalem’s Old City,” National Geographic; Encyclopedia Britannica, s.v. “Landscape of Jerusalem, City Layout.”

This massive project took five years to complete (1536–41). The city was encircled by a wall, 40 feet high and 2 miles long, and had 34 towers and 7 gates. It was the first time the city had proper fortification in more than 300 years. Karen Armstrong, Jerusalem: One City, Three Faiths (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996), 324.

Armstrong, Jerusalem, 324.

“Gates of Jerusalem—Damascus Gate,” Crystal Links.

Mariam Shahin, Palestine: A Guide (Northampton, MA: Interlink Books, 2005), 307.

“Gates of Jerusalem,” Madain Project.

“Jerusalem Visitor Guide,” Bab al-Sahira (Herod’s Gate).

Shahin, Palestine, 310.

“The Lion’s Gate: A Solid Defense Line of Jerusalem,” Al-Quds Jerusalem.

“The Lion’s Gate.”

“The Lion’s Gate.”

Sylvia Auld and Robert Hillenbrand, Ottoman Jerusalem: The Living City, Part I (1517–1917) (London: Altajir World of Islam Trust, 2000).

“Gates of Jerusalem,” Madain Project.

Wikipedia, s.v. “Lions’ Gate,” last modified November 24, 2021, 22:12.

Wikipedia, s.v. “Gates of the Old City of Jerusalem,” last modified October 24, 2021, 08:29; “Gates of Jerusalem—Golden Gate,” Crystal Links.

“Dung Gate, Jerusalem,” GPS My City.

Shahin, Palestine, 309.

Shahin, Palestine, 309; Benny Morris, 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009).

Adam Abu Sharar, “The Shop at Bab al-Khalil,” Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 15 (2002); Shahin, Palestine, 309.

Johann Büssow, Hamidian Jerusalem: Politics and Society in the District of Jerusalem, 1872–1908, vol. 46 of The Ottoman Empire and Its Heritage: Politics, Society and Economy, ed. Suraiya Faroqhi, Halil Inalcik, and Bogac Ergene (Leiden: Brill, 2011), 496.

“New Gate—Jerusalem,” Bible Walks; “Gates of Jerusalem,” Madain Project; Shahin, Palestine, 307.