The European Religious Roots of the Holy Basin

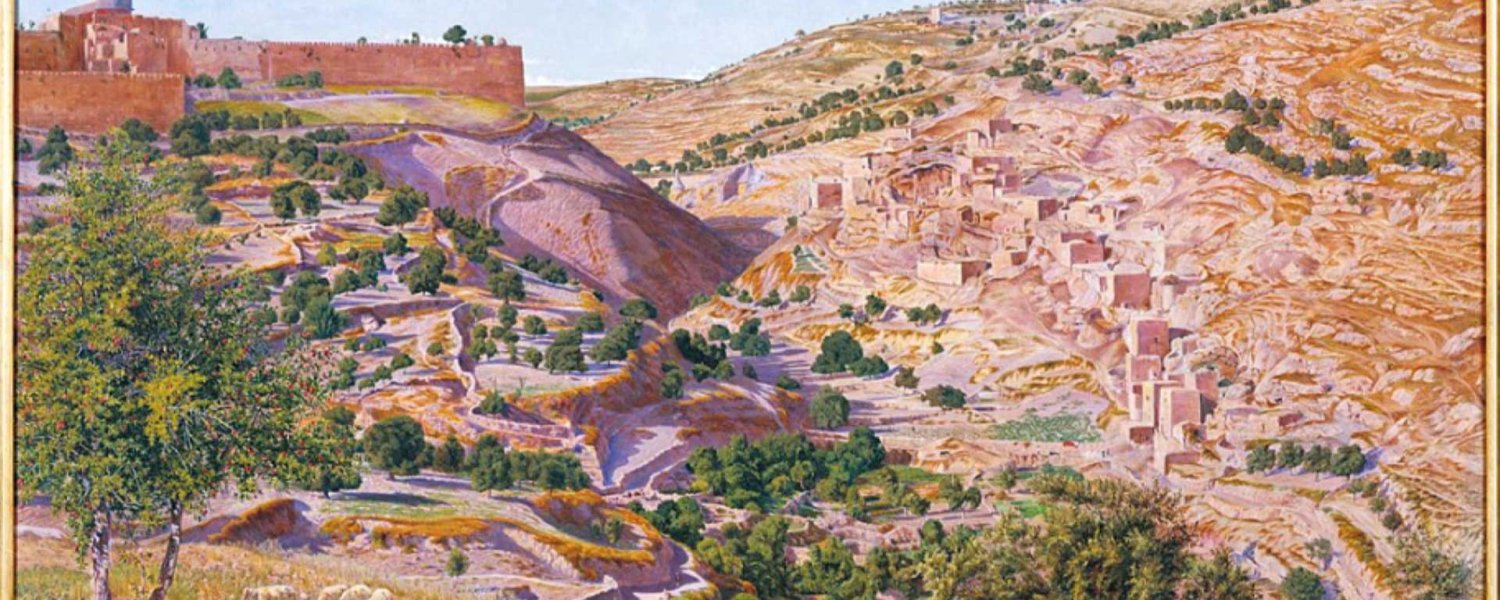

Credit:

Wikipedia

What and Where Is Jerusalem’s Holy Basin, and Why Is It So Significant?

Snapshot

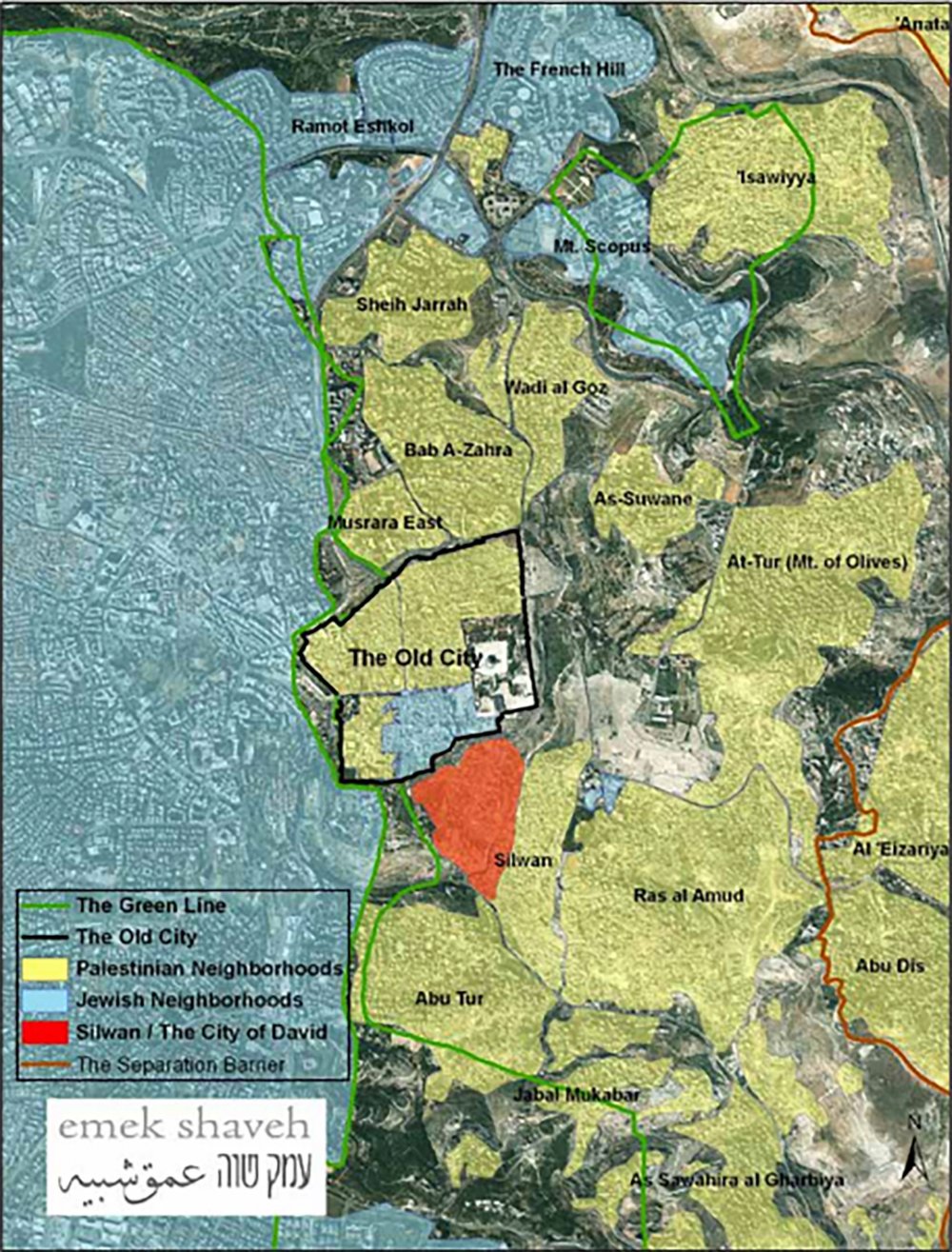

Jerusalem’s Old City and its immediate surroundings have been a site of great religious and political significance and controversy since Europeans first viewed them separately from the remainder of the city in the mid-19th century. And since Israel occupied East Jerusalem in 1967, this area, with its high concentration of religious sites, has witnessed extensive efforts at Judaization by Israel, displacing Palestinian communities in the process. This Backgrounder explores the historical emergence and politicization of this area, known by Israelis as the Holy Basin, into a site of tremendous contestation, and as a perennial issue in the failed rounds of negotiations.

Arguably no other piece of land in the world is as contested as the three square kilometers that make up Jerusalem’s Old City and its surrounding environs—the so-called Holy or Historic Basin.1 At once lying at the heart of Israeli-occupied East Jerusalem, the area is also the location of some of the holiest sites to Jews, Christians, and Muslims across Palestine and the world. Indeed, the site has seen its fair share of dramatic events for centuries, increasingly so since Israel’s 1967 occupation of East Jerusalem.

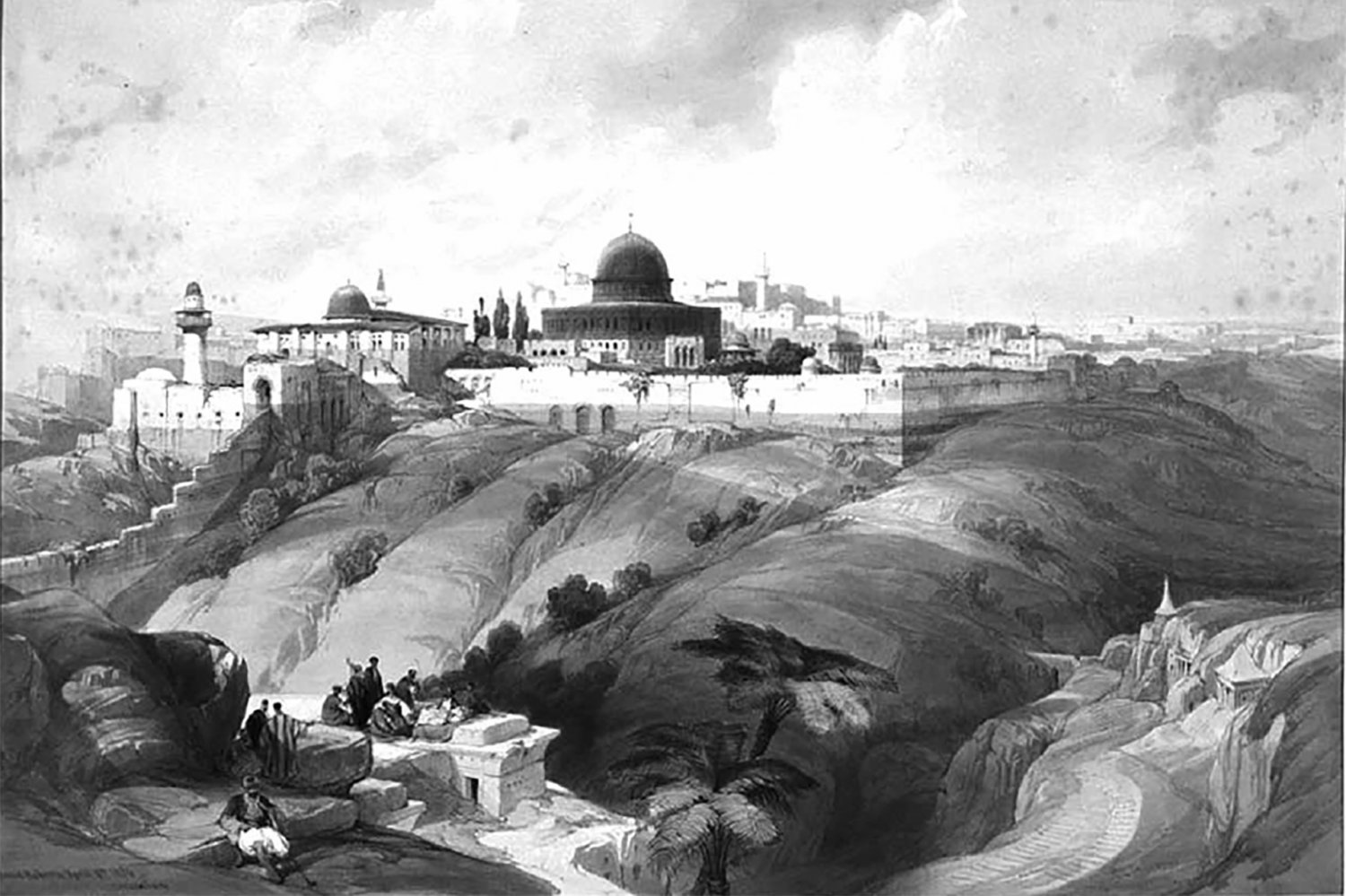

The Old City of Jerusalem and its surrounding area have long been considered separately from the remainder of the city due to the Old City’s majestic walls and the high concentration of religious sites within and around it—visible, underground, proven, or fabricated.2 But, as Wendy Pullan and Maximilian Sternberg argue, “the middle of the nineteenth century witnessed the first explicit attempts to address the area inside and outside the wall as one city,”3 and the impetus was foreign and religious. In other words, isolating this part of the city in rhetoric and, later, through city planning reflected a modern European religious obsession with setting “Jerusalem as the prime locus of the sites of the Bible in need of Western archaeological excavation.”4 In the Orientalist European imagination, therefore, Jerusalem is its holy sites, and archaeology is needed to unearth and preserve them—a view that spread and lingered among Europeans and Zionists, in large part due to the spate in photography and art about Jerusalem and its Old City landscape.

This new and foreign perspective on the heart of the ancient city set a precedent for how its later conquerors viewed and administered it. By the time British forces occupied Jerusalem in December 1917, British town planners largely dealt with the area of “the Old City and its environs” separately from the rest of the city, including the expanding New City neighborhoods west of the Old City (see The West Side Story, Part 1: Jerusalem before “East” and “West”).5 In fact, the first known outline of the area as a specific zone was drafted by British city engineer William McLean in 1918. In later British sketches of the city, other terms for the area included “antiquity zone,” “greenbelt around the city wall,” and “archaeology zone.”6 The subsequent occupiers of Jerusalem, the Israelis, inherited this practice of demarcating this area in city planning and policy, politicizing the heart of the ancient city in unprecedented ways.

The Holy Basin under Israeli Occupation

It was the Israeli government that took the obsession with the heart of Jerusalem and its religious sites to new extremes. This began with Israel unilaterally and illegally annexing East Jerusalem, including the Old City and its surroundings, in 1967, and razing the Moroccan Quarter (Haret al-Maghariba) to build the prayer plaza across from the Western Wall. This is to say that Israel’s declaration of its sovereignty over the entirety of Jerusalem—with its expanded municipal borders—implicity included “the Old City and its environs,” violating Jordanian custodianship over the city’s Christian and Muslim sites, as well as the precarious Status Quo Agreement that had been in place since 1852 (see What Is the “Status Quo”?). The Israeli government then confirmed its de facto sovereignty over every part of Jerusalem in its 1980 quasi-constitutional Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel, in which the Knesset determined that “Jerusalem, complete and united” is the capital of Israel and the seat of the president, Knesset, and Supreme Court.7

The issue became ever more delicate in the early 1990s when Palestinian and Israeli representatives sat down at the negotiations table. The Oslo Accords did not resolve many issues, including Jerusalem, rendering it a “final status issue” in great part because of questions of sovereignty and control over the Old City and its immediate surroundings.8 Subsequent efforts to reach a “just and lasting peace” between the Israelis and Palestinians invariably included intractable negotations about the heart of Jerusalem and its immediate surroundings. And in 2000, during the Camp David II talks, Israeli negotiators coined the term “Holy Basin” as “a special regime for the Old City and environs; they regarded it as a pillar for the future status of the city within the framework of a two-state solution.”9

The term is used in a variety of Israeli and Western policy and media circles, but not by Palestinians, who view it as another Israeli attempt to create “facts on the ground” that justify Israeli expropriation of Palestinian land and the displacement of Palestinians (see Living with the Ever-Present Threat of Expulsion) through a number of archaeological and tourist projects.10 In fact, Palestinians do not have a name for the Holy Basin and instead, view it as part of the city’s continuous landscape. Thoroughly politicized, the Holy Basin has thus become a charged term in Jerusalem, one that is continually being redefined as Israeli occupation forces, settler organizations, and the Israeli government advance their plans to Judaize the core of the ancient Jerusalem (see Israeli Government Pumping Millions into Judaizing Jerusalem, Erasing Palestinian Heritage).

Delineating the Parameters of the Holy Basin

Since the turn of the 21st century, one of the recurring issues with administering and planning the area outside the Old City walls continues to be defining its boundaries. With so many conflicting parties with vested interests in the area, disagreements have emerged not only over border placement, but also over the historical significance and veracity of religious sites. In 2004, two Israeli researchers at the Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, Kobi Michael and Moshe Hirsch, proposed a solution for defining and administering this complex area. The proposal was modeled on West Berlin after World War II, when Britain, France, and the US shared responsibility of its administration.11

“The Holy Basin could also be administered as an autonomous independent entity by an international force,” Michael argued.12 He elaborated that the international force “would be the source of authority and would delegate appropriate functions to Israel and the Palestinians, subject to arrangement or agreement between the parties.” This force would also serve as an impartial arbiter during times of disagreement, allowing it to “prevent stalemate or deterioration or friction.”13

In a study coauthored by Michael and Hirsch, the pair proposed boundaries of the Holy Basin for the first time:

On the west, it runs along the length of the Old City wall until its southwest corner.

On the south, it runs the course of the Ben-Hinnom Valley to the area south of the wall around the Haceldama (Field of Blood) Monastery; then northward to the eastern fence of Peter in Gallicantu Church, including the graveyards in its vicinity; from there to the southern wall of the Old City until the Southern Wall excavations (the Ophel Archaeological Gardens); from there to the Jewish cemetery that borders Silwan until the Ras al-Amud Road and along its southern side, so that the cemetery on the Mount of Olives would be included within the Basin.

On the east, along the length of the Jewish burial plots on the Mount of Olives to the section of the wall around the Russian Church of the Ascension, Makassed Hospital, around whose western side the boundary would run, leaving the hospital out of the basin; from there along the walls of Viri Galilei, the holiday residence of the Greek Orthodox patriarch.

On the north, from Viri Galilei to the northeastern corner of the Old City wall (the Stork Tower) and along the wall to the Schmidt Girls’ College on Nablus Road, until the Damascus Gate in the Old City wall, and along the length of the wall until the Jaffa Street corner.14

The authors considered these the reduced parameters of the area—measuring 2,210 dunums—and proposed additions for expanding the area “subject to the conditions and interests of the parties.” The additions could include the City of David, the Silwan Hill of Evil Counsel area, and the Saint George compound, they argued, bringing the boundaries of the Holy Basin to 2,502 dunums. The authors were determined to reject the premise of partitioning the Holy Basin, which had recently been proposed in the Geneva Initiative.15 As Michael put it, “As soon as you partition it, you harm its vitality and its essence as a single entity that possesses a certain character.”16

But with the rise of the extreme right in successive Israeli governments since the Second Intifada erupted in 2000, any chance of relinquishing Israeli control over any part of Jerusalem continues to be an impossibility. Indeed, it was reported that former Israeli prime minister Ehud Olmert even met the Palestinian leadership in secret in 2008 and proposed “international control of the holy basin and a joint team to administer East Jerusalem until a final settlement was agreed.” However, his successor, Benjamin Netanyahu, rejected Olmert’s proposal and any division of responsibility over the city and subsequently intensified Israeli control over the Holy Basin.17

In 2018, two other Israeli analysts at the International Crisis Group, Ofer Zalzberg and Yonathan Mizrahi, proposed “setting up a team of Israeli, Palestinian and international (Jordanian, Egyptian, Vatican, etc.) professionals, who would together work toward fostering a multicultural and tolerant historic core to the city.”18 This came weeks after former US president Donald Trump moved the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, which the analysts saw as an opportunity for the US to play the role of mediator “to help the sides identify a middle path.” The US would also work to “ensure that the actions of each party do not contravene the red lines of the other,” the authors asserted.

Yet they also noted:

In recent years, the Holy Basin—which for our purposes comprises the Old City and the surrounding areas such as Silwan, Mount Zion and Mount of Olives, most of which lie in east Jerusalem territory that Palestinians claim as their future capital—has seen excavations of unprecedented scope, followed by massive investment to turn antiquity sites into tourist attractions and develop new sites of Jewish worship.19

They elaborated that these projects, which include a cable car (see Controversial Cable Car Project Sparks Outcry as City Orders Land Expropriation from Silwan Residents), suspension bridge, and other excavations on Palestinian lands in Silwan, directly south of the Old City, are part of a larger Israeli goal of “recreating the historic city, blotting out non-Jewish parts of its history and highlighting Jewish ones, especially the First and Second Temple periods” (see Israel’s Disneyfication of Jerusalem Seeks to Erase Palestinians’ Historic Presence). Successive Israeli governments have shown no indication of reducing or curtailing these projects, which certainly contravene Palestinian red lines.

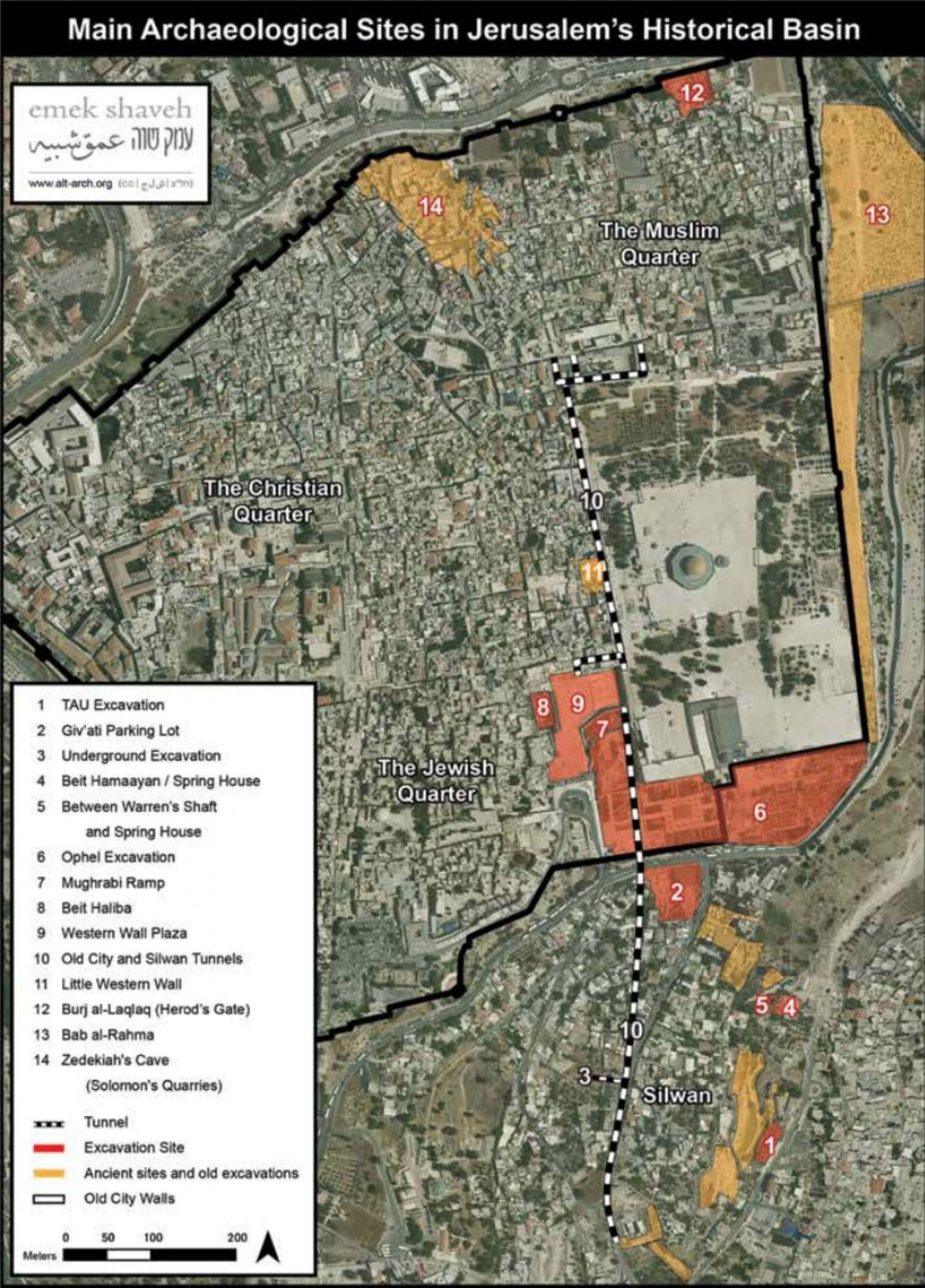

The extent of the projects and the many parties involved cannot be overstated. Emek Shaveh, an Israeli NGO that counters the politicization of archaeology, lists the different bodies, governmental and otherwise, that have vested interests in the Holy Basin. On the Israeli side, powerful actors include:

- The Elad Foundation, “a private foundation established in the late 1980s with a mission to take over homes of Palestinian residents in Silwan and settle them with Jews.” In 2002, the extremist foundation assumed management of the largest archaeological project in Silwan, the City of David Archaeological Park, subsequently undertaking massive excavations throughout the area at the expense of its Palestinian residents. With a budget of millions of NIS annually, Elad has managed to fabricate a historical narrative of the City of David, turning the area into a sophisticated, high-tech, and audiovisual tourist attraction, erasing any non-Jewish history from the site.

- The Israel Antiquities Authority, the governmental body responsible for all archaeological activities in Israel, including excavations in the Holy Basin. “Any construction work, excavation, development or renovation in the Historic Basin and in the Old City in particular” must be approved by this body.

- The Nature and Parks Authority (INPA), another governmental body tasked with “declaring and protecting national parks and nature reserves,” including in the Holy Basin. The INPA, in collaboration with Elad and other bodies, has seized control over a sizeable area of Silwan, which includes the City of David Park, and declared it the Jerusalem Walls National Park. This means that any construction or excavation work in the area requires INPA approval, leaving Palestinians with little chance of developing their neighborhoods.

- The Jerusalem Municipality, which serves as the governing body for most of the development projects in the Holy Basin. The municipality “exerts its influence through the Jerusalem Development Authority (JDA), a municipal-government company that received hundreds of millions of shekels for the development of East and West Jerusalem.”20

- The JDA, which is a statutory corporation under the jurisdiction of the Ministry for Jerusalem Affairs and Jewish Heritage and the Jerusalem Municipality. It funds most of the work carried out in the Holy Basin, including the controversial cable car project.

- The Ministry of Jerusalem Affairs and Jewish Heritage, authorized by the JDA.

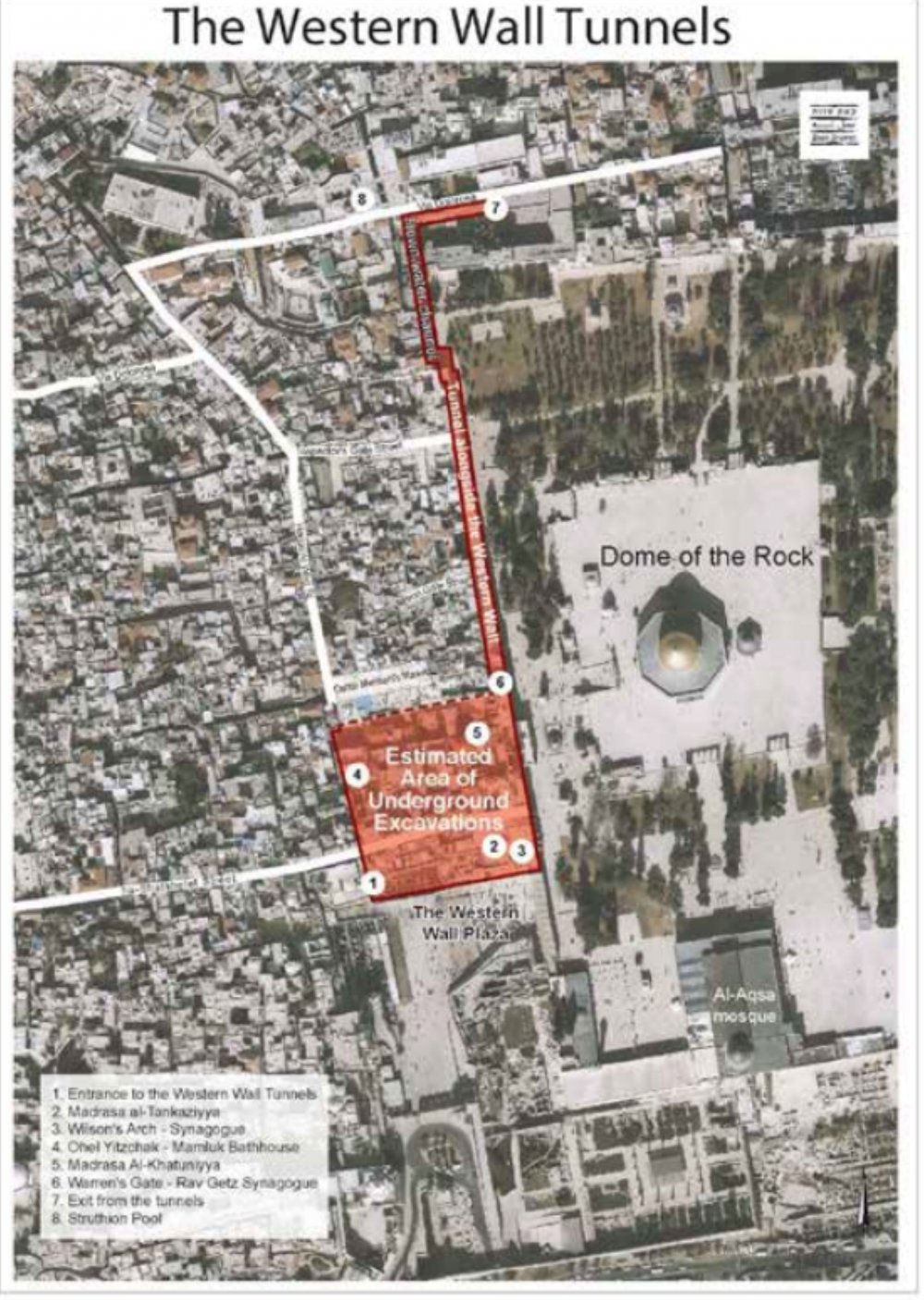

- The Western Wall Heritage Foundation, which is a governmental foundation in charge of the Western Wall Plaza and tunnels, including funding the excavations under the Muslim Quarter.21

The only body representing the Palestinians in the Holy Basin is the Islamic Waqf, which is responsible for Muslim holy sites in the Haram al-Sharif as well as its properties in the Old City. That the Haram al-Sharif, known to Jews as the Temple Mount, is under the administrative authority of the Islamic Waqf (as it has been for centuries) has caused tremendous controversy at the holy site, with Israeli settlers, governmental authorities, and occupation forces repeatedly storming the area to attempt to assert Jewish control. This has led to outbreaks of violence and even triggered the eruption of the Second Intifada in 2000.

A Global Concern at the Heart of Failed Negotiations

The sanctity and safety of the Holy Basin’s religious sites is of paramount concern for Israelis and Palestinians alike, and it has garnered tremendous international attention. Indeed, the city’s religious sites are of great significance to political and religious leaders regionally and globally, with the Jordanian monarchy maintaining custodianship over the Muslim and Christian sites of the city, and the Vatican, among other powerful Christian ecclesiastical bodies, insisting on its say in the city’s Christian sites as well. With so many external actors with vested interests in the Holy Basin, most negotiations between Palestinian and Israeli leaders since the Oslo Accords have necessitated a mediator. The US has assumed that role but has not been successful.

With the failure of the Oslo Accords and the rising tensions in Jerusalem in the latter half of the 1990s, the US ramped up its efforts to resolve this most significant of final status issues. In July 2000, then prime minister Ehud Barak and Palestinian Authority (PA) Chairman Yasser Arafat met US President Bill Clinton at Camp David to discuss the issue of the status of the Haram al-Sharif/Temple Mount.22 The failed proposals of the summit are summarized succinctly by Ir Amim, the Jerusalem-based NGO closely following political developments in the city:

During the meeting, Israel proposed a complex model of sovereignty and control. The proposal included full Palestinian control of al-Quds, comprised mainly of the outer circle of Palestinian neighborhoods, in exchange for expanding the city limits and annexing to Israel the nearby settlements.

The Palestinian neighborhoods closest to the city center and the historic basin would remain under Israeli sovereignty, but the Palestinians would be given municipal autonomy in them. In the holy basin and the Christian and Muslim quarters of the Old City there would be formal Israeli sovereignty but the administration and functional government would be Palestinian. Israel also agreed to establish a Palestinian presidential compound in the Muslim quarter. According to the proposal, Haram al-Sharif would be under functional Palestinian control, including the right to wave their flag at the site, but sovereignty would remain Israeli.

The Palestinians, for their part, demanded complete sovereignty and control of all of East Jerusalem including the holy sites, first and foremost Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif, and the dismantlement of all of the Israeli neighborhoods built beyond the Green Line. The Palestinians also objected to the Israeli demand to establish a prayer area for Jews on Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif, and completely rejected Israel’s religious and historic connection to the holy places. An alternative proposal that was also discussed at the meeting would have given Palestinians sovereignty over the surface of the mountain and Israel sovereignty beneath ground level, including the Western Wall, but the Palestinians rejected the proposal.23

While the July talks failed, the world’s attention quickly turned to the eruption of the Second Intifada on September 28, 2000, following Israeli opposition leader Ariel Sharon’s provocative entry into the Haram al-Sharif in the company of security forces. The subsequent five-year Palestinian uprising is also known as the al-Quds Intifada, precisely because of the significance of that day.

In December 2000, Clinton proposed a political settlement to Jerusalem and the Holy Basin. The so-called Clinton Parameters laid out the following:

Israel would have sovereignty over the Western Wall and “symbolic ownership” of Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif, which would be under Palestinian sovereignty. The parties would share the archaeological and structural excavations underneath the mountain. East Jerusalem and the Old City would be divided along ethnic-demographic lines: the Israeli neighborhoods would be physically connected to the Western part of the city and remain under Israeli sovereignty. The Palestinian neighborhoods would be transferred to Palestinian sovereignty, physically connected to the West Bank and constitute the capital of Palestine. Israel officially accepted the Clinton parameters for division of sovereignty in Jerusalem with reservations. The US administration accepted Israel’s willingness to negotiate on that basis and rejected the more substantial reservations submitted by the Palestinians.24

More than 30 meetings took place between July 2000 and January 2001 to reach a solution to Jerusalem and its religious sites. The last round of talks held in Egypt’s Taba in January 2001 were abruptly suspended, and the Intifada continued to rage.

Despite notable attempts at resuming negotiations in 2002—including the “Quartet’s” so-called Roadmap to Peace in June and the Arab League’s Arab Peace Initiative (API)—the most significant effort to resolve the issue of Jerusalem was the December 2003 Geneva Initiative. Taking into account all previous agreements, the Geneva Initiative “provided a detailed practical interpretation of the Clinton parameters for the division of sovereignty in Jerusalem while maintaining its function as the capital of two states.”25 This unofficial initiative ended in failure, as well.

Emek Shaveh summarizes the Geneva Initiative’s solutions to the Holy Basin as follows:

Like the Clinton Parameters, the Geneva Initiative also proposed dividing the Old City so that the Jewish Quarter and the Western Wall would be governed by Israel and the Christian and Muslim quarters would be under Palestinian control. The Mount of Olives, the Western Wall tunnels and the Tower of David Museum would also come under Israeli authority. The initiative proposed policing and oversight mechanisms for the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif and in the Old City.26

With the failure of all negotiations, and with the increasing radicalization of Israeli leadership over the last few years, Judaization efforts in the Holy Basin have proceeded at a staggering pace through destructive excavations and settlement projects that displace Palestinians and demolish their homes, especially in Silwan. As Emek Shaveh explains, “the settlement activities in the Historic Basin are part of the larger picture of settlement in East Jerusalem and the West Bank” though they take on the form of “extensive archaeological excavations” mostly carried out by the Israel Antiquities Authority and funded by settler groups or the government. These projects are “driven by a national agenda altering the identity of the city above and below ground.” Indeed, though they are ostensibly meant to develop sites for tourism, they “impact the geo-political landscape in significant ways . . . extending from Silwan, along the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif, reaching the Via Dolorosa in the Muslim Quarter.”27

These destructive projects in the Holy Basin, both aboveground and underground, include the Shalem Plan, a NIS 50 million project to construct “a large continuum of archeological tourist sites above and below ground from Silwan to the Old City” that would be “insulated from the contemporary Palestinian environment in which it is situated”; the Kedem Center, a 15,000 square meter visitor center between the Old City and the entrance to Silwan; the cable car to transport tourists between West Jerusalem and Silwan; tunnels referred to as “the Pilgrim Route” that run underneath Palestinian homes in Silwan and that supposedly date back to the Roman period; and the Western Wall tunnels, comprising an area of hundreds of meters of excavations housing synagogues, museums, and other tourists sites under the homes of Palestinians in the Muslim Quarter.28

Today, as the war on Gaza continues, and as is often the case with political escalations between Israeli occupation forces and Palestinians, Jerusalem is a major site of turmoil. Since October 7, Palestinians in the city have come under increasing Israeli oppression, including arrests, beatings, detentions, and restrictions on access and mobility—especially in and around the al-Aqsa Mosque compound. Civilians have been alarmed to a disturbing extent (see Mohanad Darwish, “I’ve Never Been Surrounded by This Many Rifles in My Entire Life”).

Meanwhile, Israeli authorities and settler groups continue to expropriate Palestinian lands in the Holy Basin for religious tourist projects, displacing and dispossessing Palestinians in the process. And because what happens in the Holy Basin can be considered a microcosm of larger Israeli settler-colonial plans across the city and much of historic Palestine, Palestinians view these ever-accumulating, Israeli-created “facts on the ground” with deep alarm.

Notes

Both “Holy Basin” and “Historic Basin” are used to refer to the same area. This Backgrounder uses the former term.

For more about Israel’s fabrication of biblical history in the interest of expanding its tourist industry in Palestinian areas of the Holy Basin, see Sonia Espinosa-Najjar, “Israeli Heritage Tourism in Wadi Helweh: Making What Is Out of Mind Out of Sight,” Journal of Palestine Studies (2024): 1–10.

Wendy Pullan and Maximilian Sternberg, “The Making of Jerusalem’s ‘Holy Basin,’” Planning Perspectives 27, no. 2 (2012): 228.

Pullan and Sternberg, “The Making of Jerusalem,” 228.

Pullan and Sternberg, “The Making of Jerusalem,” 230.

Pullan and Sternberg, “The Making of Jerusalem,” 230.

“Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel (1980),” ECF, accessed April 12, 2024.

“Jerusalem as a Political Issue,” Ir Amim, accessed April 12, 2024.

Pullan and Sternberg, “The Making of Jerusalem,” 233.

“Jerusalem as a Political Issue.”

This plan was later developed into a policy report by a work group that included Michael and Hirsch. The 2010 work group, headed by legal scholar and researcher at the Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Ruth Lapidoth, produced a report titled “The Historic Basin of Jerusalem Problems and Possible Solutions,” published by the Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies. It included 13 contributors, none of whom were Palestinians. The report recommended much of what Michael and Hirsch had proposed years prior. See the report here.

Dalia Shehori, “Modeling Jerusalem’s Holy Basin on West Berlin,” Haaretz, January 19, 2004.

Shehori, “Modeling Jerusalem’s Holy Basin.”

Shehori, “Modeling Jerusalem’s Holy Basin.”

Shehori, “Modeling Jerusalem’s Holy Basin.”

Shehori, “Modeling Jerusalem’s Holy Basin.”

“Jerusalem as a Political Issue.”

Ofer Zalzberg and Yonathan Mizrahi, “Peace Starts in Jerusalem’s Holy Basin,” International Crisis Group, May 30, 2018.

Zalzberg and Mizrahi, “Peace Starts.”

Zalzberg and Mizrahi, “Peace Starts.”

Zalzberg and Mizrahi, “Peace Starts.”

“Historic Jerusalem: Challenges and Proposals for Interim Steps,” Emek Shaveh, September 10, 2018.

For more on the significance of Jerusalem in the Camp David summit, see Mick Dumper, “Constructive Ambiguities? Jerusalem, International Law and the Peace Process,” Jerusalem Quarterly 34 (2008): 13–40.

“Jerusalem as a Political Issue.”

“Jerusalem as a Political Issue.”

“Jerusalem as a Political Issue.”

“Historic Jerusalem.”

“Historic Jerusalem.”

“Historic Jerusalem.”