Chapter 1, the longest in the book, covers roughly 4,200 years. (The 22-page chronology at the end of the book is especially helpful in giving the reader a handle on the succession of rulers.) This chapter covers the Bronze Age, the period of Egyptian control, the Canaanite city, the City of David, and the extension to the Temple Mount. As with most historical accounts of antiquity, the authors highlight Jerusalem’s periods of wars, destruction, and reconstruction throughout this extensive span of time; they argue that the Temple of Jerusalem had “a fundamental role, at once social, political, and religious” and with its destruction and reconstruction during the sixth century BCE, “conferred on the city, little by little, its specificity and its greatness.”4

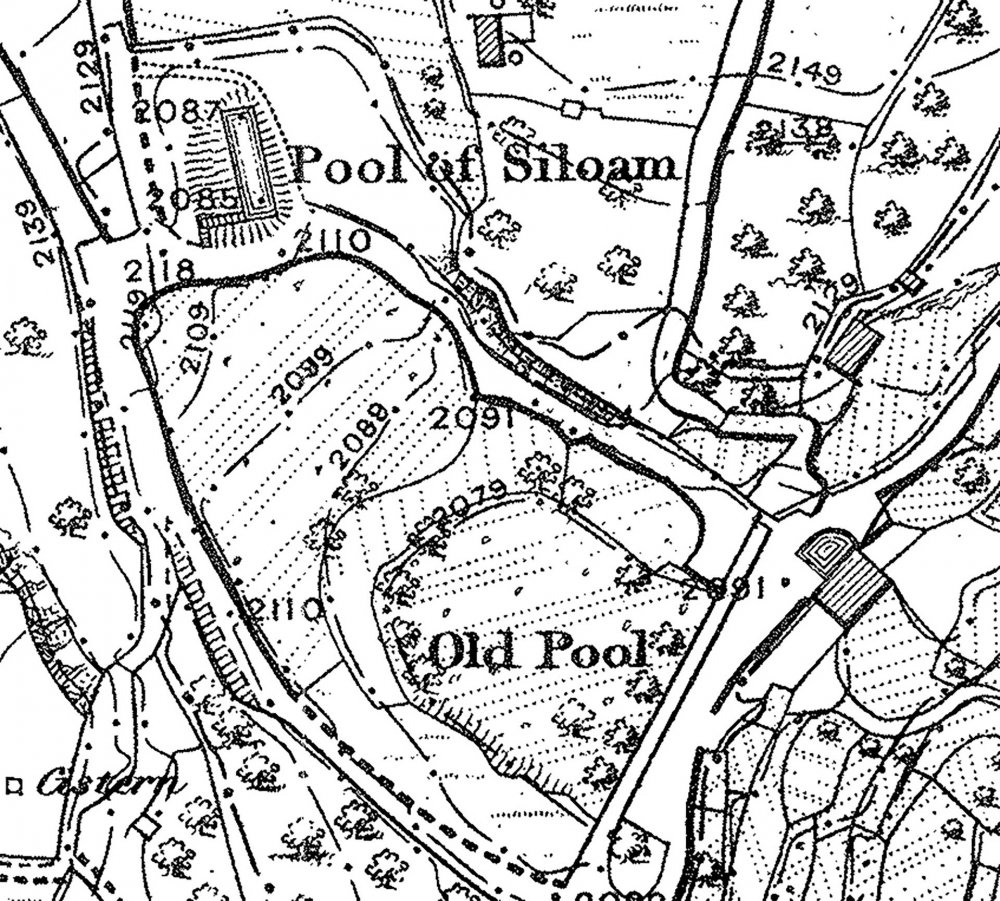

By the eighth or seventh centuries BCE, Jerusalem had experienced an urban boom and “was thus an extensive, developed, and prosperous city, a true religious and administrative center of the Kingdom of Judah” that stretched across 148 acres.5 The Babylonian invasion and destruction of the First Temple in 586 BCE was followed by the Persian period and Jerusalem’s rebirth. Then, the rule of the Ptolemies during the Hellenistic era was a period of expansion across the hills to the west of the city, an area then known as the Upper City.

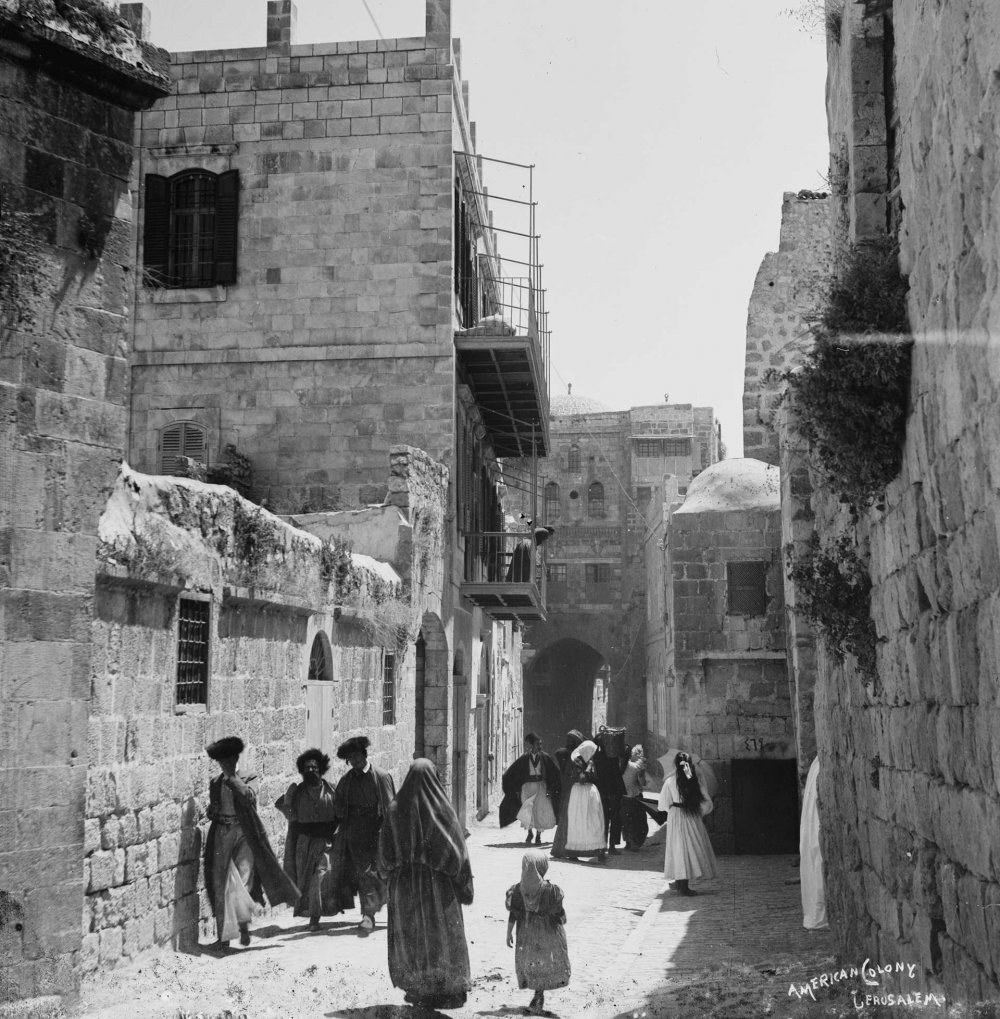

The archaeological evidence indicates that Jerusalem was a prosperous town in the first century. The authors describe that neighborhoods consisted of diverse populations and standards of living, largely thanks to King Herod, who was an enthusiastic builder, leaving his mark on the city and beyond, including the palaces of Jericho. In Jerusalem, he built two towers and a palace in what is now the Old City’s Armenian Quarter; he restored Jerusalem’s first wall and built a second one; and he renovated and enlarged the Temple, with impressive results. By 45 CE, the city covered 1.8 square kilometers and was home to 90,000 residents. It also became “a city of pilgrimage, to a degree never before reached in its history.”6