Introduction

Credit:

Ahmad Gharabli/AFP via Getty Images

A Jerusalem Expert Explains Israel’s Tsunami of Settlement Plans in East Jerusalem

Snapshot

Jerusalem Story sat down with Daniel Seidemann, executive director of Terrestrial Jerusalem, an Israeli nonprofit tracking political developments in Jerusalem, to discuss Israel’s accelerated settlement development in East Jerusalem in 2023. While many of these plans are not new, Seidemann explains that the speed at which they are advancing is cause for concern.

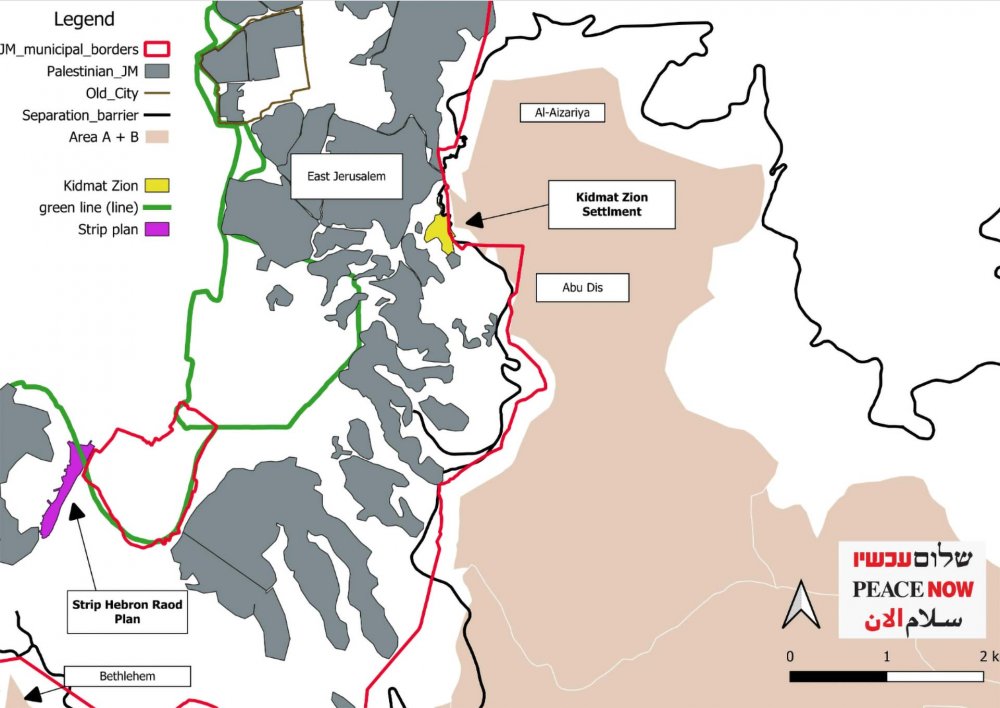

On September 11, 2023, the Jerusalem District Planning Committee approved plans to construct nearly 4,000 additional residential settlement units in East Jerusalem.1 These include 384 units as part of the new Kidmat Tzion settlement enclave, set to be built in an area only inhabited by Palestinians along the border between the occupied East Jerusalem neighborhood of Ras al-Amud and the Palestinian village of Abu Dis. As a result, Kidmat Tzion will be the largest settlement enclave in East Jerusalem.2

Another settlement plan, Giv’at HaMatos D, calls for 3,500 housing units and 1,300 hotel rooms along the Hebron Road in southern Jerusalem.3 Additionally, since the start of 2023, Israel has advanced 30 zoning plans, totaling 18,223 housing units, for East Jerusalem settlements. According to Ir Amim, a Jerusalem-based Israeli nonprofit organization monitoring political developments in the city, the scale of settlement activity in 2023 is predicted to surpass the record number of housing units advanced in East Jerusalem in 2022.4

Daniel Seidemann, founder of Ir Amim and executive director of Terrestrial Jerusalem, shares his insights on Israel’s settlement acceleration in Jerusalem, and what it means for the political future and demographics of the city.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Jerusalem Story: In September 2023, the Jerusalem District Planning Committee approved about 4,000 settlement units in East Jerusalem. What is so significant about these plans?

Daniel Seidemann: At Terrestrial Jerusalem, we’ve been monitoring all settlement developments over the last several months, and we have a long list. While most of these are not new and were initiated at some stage by prior governments, the new ones were developed after the February 26, 2023, Aqaba Summit, during which Israel committed to stop discussion on any new settlements for four months.

The most significant of these new settlements can be put into two categories.

First, there are the large settlement neighborhoods on the southern plank of Jerusalem, which cumulatively create a buffer zone between East Jerusalem and Bethlehem, effectively sealing the border and detaching Bethlehem from East Jerusalem. In this seal, Israel constructed the settlements of Har Homa and Har Gilo [see The Three Israeli Settlement Rings in and around East Jerusalem: Supplanting Palestinian Jerusalem], the latter of which is in the West Bank and is being expanded. Then, there is the development plan in Gilo, known as Har Homa West. This is a new neighborhood of the Lower Aqueduct, which former prime minister Yair Lapid started, and it is being expedited.

But most significantly, there is the Giv’at HaMatos D settlement, which was designated for 1,500 hotel rooms. The government is trying to hide that this is a settlement by calling it New Talpiot Hill. But it is not a hill, and it is not in Talpiot. It is a settlement in occupied East Jerusalem.

Giv’at HaMatos D is the most significant settlement plan taking place in Jerusalem today, because it severs the Palestinian neighborhood of Beit Safafa from the West Bank. In theory, it would be possible to incorporate Beit Safafa into a future Palestinian state, but not if Giv’at HaMatos is built.

Second, there are the settlement neighborhoods being built in the area surrounding the Old City, and these tend to be smaller neighborhoods with thousands or tens of thousands of units. But settlement enclaves like Ma‘ale HaZeitim, Ma‘ale David, Beit Orot, and Shimon HaTzadik in the Palestinian neighborhoods of Ras al-Amud, Mount of Olives (Jabal al-Zaytun), and Sheikh Jarrah are immense.

There are three new settler enclave schemes, the most prominent of which is Kidmat Tzion. It will entail 384 residential units, which will make it the largest settlement enclave in East Jerusalem since 1967. Currently, the largest one is in Ras al-Amud, with around 126 units.5 It will also be in an area that is exclusively Palestinian on the border between Abu Dis and East Jerusalem.

There is a second project for hotel rooms known as Nof Zahav, and it is located on the ridge of Armon HaNetziv [in the heart of the Palestinian neighborhood of Jabal Mukabbir—Ed.]. In the early 1970s, it was decided that Talpiot Mizrach would be built on the far side of the Old City, so as not to destroy the skyline. But Nof Zahav is on the ridge, the first of its kind.

One more plan by the Ministry of Justice, Umm Lison, is also set to be built inside the Palestinian neighborhood of Jabal Mukabbir. In 1967, the Israeli government decided that it would not build inside existing Palestinian built-up areas, and that it would build around them instead. But 2023 marks the first year the government plans settlements inside Palestinian areas. These include the enclave of Giv’at HaShaked, which is on the northern flank between Beit Safafa and Sharafat, and which has already been approved; Umm Lison is the other.

The Giv’at HaShaked settlement is particularly noteworthy because, in 1995, Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin’s government tried to expropriate the land in order to build it, stirring international uproar. Even the United States threatened to not veto the UN’s condemnation of the plan. As a result, Rabin backed down, declaring that there would be no further land expropriations for new settlements and that the plan would be reversed. So, the uproar died down. But now, Giv’at HaShaked is planned on this same land. This would not only have a devastating impact on future political agreements; it would also be a violation of a specific US directive to the government of Israel.

JS: Who is promoting these settlement plans?

DS: Almost all of these plans started before Benjamin Netanyahu’s current government, and if Netanyahu were to be deposed tomorrow, they would not disappear. In many ways, your question is irrelevant because occupation is not what we do; occupation is what we have become. And the DNA of the settler organizations has been so successfully spliced into all of the relevant authorities: the Israel Land Authority, the office of the Custodian of Absentee Property, the Custodian General, the Ministry of Justice, and the Planning Committee, among others. They are all pre-programmed to advance the settler agenda.

This is part of successive Israeli government efforts that began with Ariel Sharon’s mission to sever East Jerusalem from the West Bank, which he started with the outer settlement ring [see The History of Israeli Settlement Expansion in and around East Jerusalem from 1967 to 1993]. The inner and core settlement rings that encircle the Old City are approved government plans in which millions of shekels have already been invested.6 These plans have become second nature, and so they will proceed unless somebody in government has the courage to stop them. And I don’t see that happening.

JS: From the data presented, it seems like settlement development has skyrocketed since this current government took over. Is this the case?

DS: I wouldn’t say that it has skyrocketed, because we’ve seen things like this in the past. I think the major changes are the cumulative impact and the pace of settlement development. Things are moving more quickly, and plans that have been in the pipeline for years are reaching fruition, which would have happened in any case [see Land Registration in Jerusalem Is a “Grand Land Theft” from Palestinians—Ir Amim’s Amy Cohen].

JS: Would you attribute these changes to the current government?

DS: In some ways, I think this government is less efficient than previous ones. I don’t see any mastermind in this government, which is an un-engageable government. It’s very unlikely that Netanyahu will pull back from any of these plans. In fact, I met with a senior US government official and told her: “I’m going to give you a list of all the bad things that are happening in Jerusalem at the moment, and I’m going to tell you something that I never thought I would say: I don’t think there’s very much that you can do about almost all of these things. There’s no mechanism for stopping the Israeli government’s plans.” But it’s important to stress that, if Yair Lapid and Naftali Bennett were still in power, they also wouldn’t change their settlement policies, even though they did cave to international power more often.7

JS: Beyond cutting off East Jerusalem from the West Bank, how do these plans affect nearby Palestinian neighborhoods?

DS: You cannot view settlements in isolation. For successive Israeli governments, there is a coherent view of what East Jerusalem should be, largely advanced in recent years through settlement construction [see Israel’s Vision of a Greater [Jewish] Jerusalem].

At its core, this view includes the denationalization of the Palestinians in a variety of ways, including coercing them into becoming Israeli citizens, though with restricted rights. For example, they would be forced to study Israeli curricula [see Israeli Government Bill Aims to Deny Funding to Palestinian Schools in East Jerusalem]; they would be arrested for flying the Palestinian flag; and they would be given incentives to study Hebrew, further detaching them psychologically and culturally from Palestinians in the West Bank—to say nothing of their physical separation [see Al-Jidar: An Instrument of Fragmentation]. And within Jerusalem, Palestinian East Jerusalem is being fragmented geographically, economically, socially, and politically in order to keep a docile, domesticated Palestinian presence in the city that Israel can handle.

Settlements are geared toward achieving this vision for the city, a vision in which Israel holds sole, hegemonic sovereignty and the Palestinians are turned into a vestigial organ.

Notes

Daniel Seidemann (@DanielSeidemann), “Thread. 1/ Breaking and important,” Twitter, September 14, 2023, 9:13 a.m.

Ibrahim Husseini, “Jewish Settler Group Submits Plans for New Settlement in Occupied East Jerusalem,” The New Arab, May 3, 2023.

Amy Cohen, “Over 18,000 Housing Units Advanced in East Jerusalem Settlements since the Start of 2023,” Ir Amim, September 21, 2023.

Cohen, “Over 18,000 Housing Units.”

Yael Freidson, “Jerusalem Set to Build Youth Club for Jews at the Heart of a Palestinian Neighborhood,” Haaretz, June 26, 2023.

“Update: Jerusalem Day 2023,” Emek Shaveh, May 29, 2023.

Mustafa Abu Sneineh, “Israel to Halt Settlement Building at Old Jerusalem Airport under US Pressure,” Middle East Eye, December 6, 2021.