What do people remember of the homes they can no longer go to, the homes placed off limits to them?

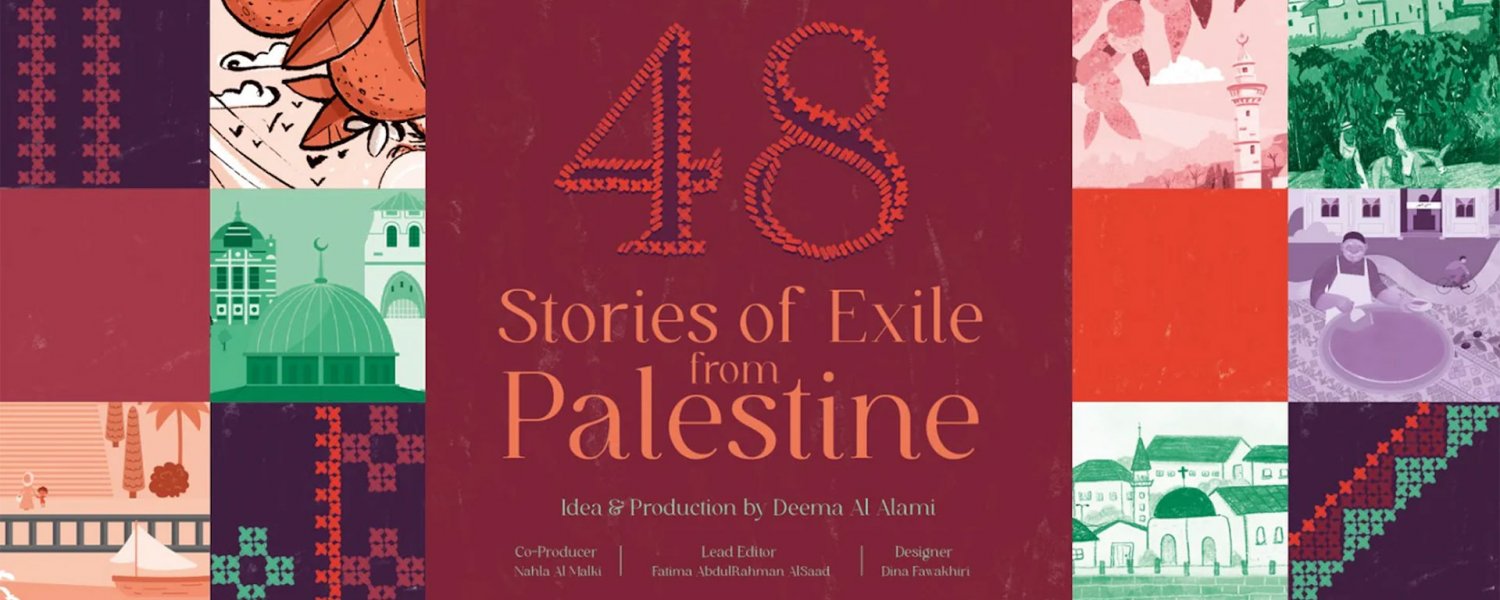

A recently published book, 48 Stories of Exile from Palestine, documents memories from 48 Palestinians who were ethnically cleansed from their homes in 1948 and 1967. It begins with the premise that the ancestors (“the living vessels of history,” as editor Deema Al Alami writes in the foreword) have experiences that must be documented while memories are intact.1 Most of the accounts in this book were written by the grandchildren of the dispossessed, who often grew up with stories of their grandparents’ struggles and imbue these accounts with real empathy. They show us the real people behind the statistics for refugees—the people who confronted events they were unable to change and, often after years of hardship, created dignified lives.

Part of the charm of the accounts is that the main figures are referred to as jiddo and teta, which translates to grandfather and grandmother in Arabic, conveying in undeniable terms that the displaced are cherished elders with real families and not just numbers. Even those who were not forced out at gunpoint left only under duress, and always with the expectation that they would return when it was safe to do so. Their descendants express their hope that return is inevitable.

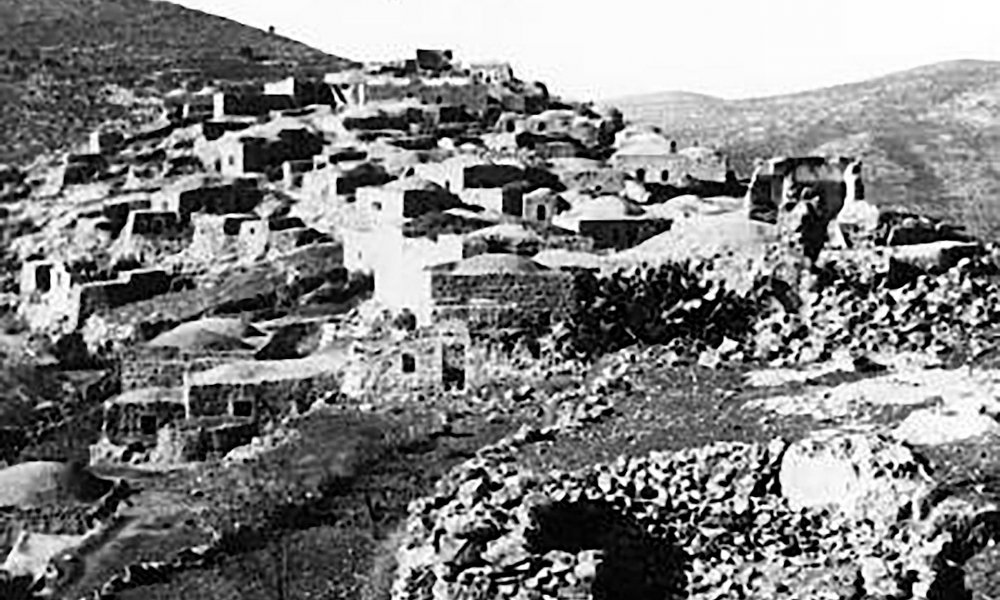

Ten of the accounts were written by the descendants of Palestinian Jerusalemites. The stories they conveyed to their grandchildren tell of deep attachment to Jerusalem and a determination that younger generations never forget their rich patrimony and their right to claim it. These Jerusalemites include a famous composer, farmer, resistance fighter, banker, mayor, and Deir Yassin massacre survivor. Their stories are summarized here.