“Is Jerusalem cursed?”

This was the question I asked the man who investigated paranormal sightings in the city. He gathered tens of accounts from people who, speaking on condition of confidentiality, vouched that they have “seen” spectral action—ghosts, deceased people, imaginary friends, and even monsters in the Old City of Jerusalem.

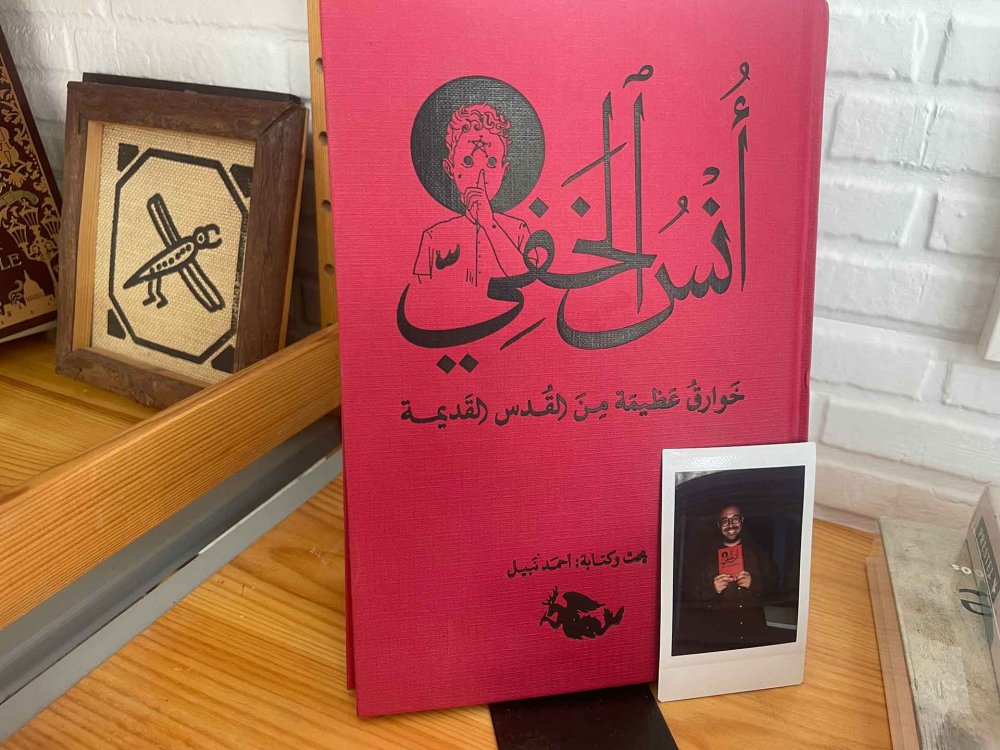

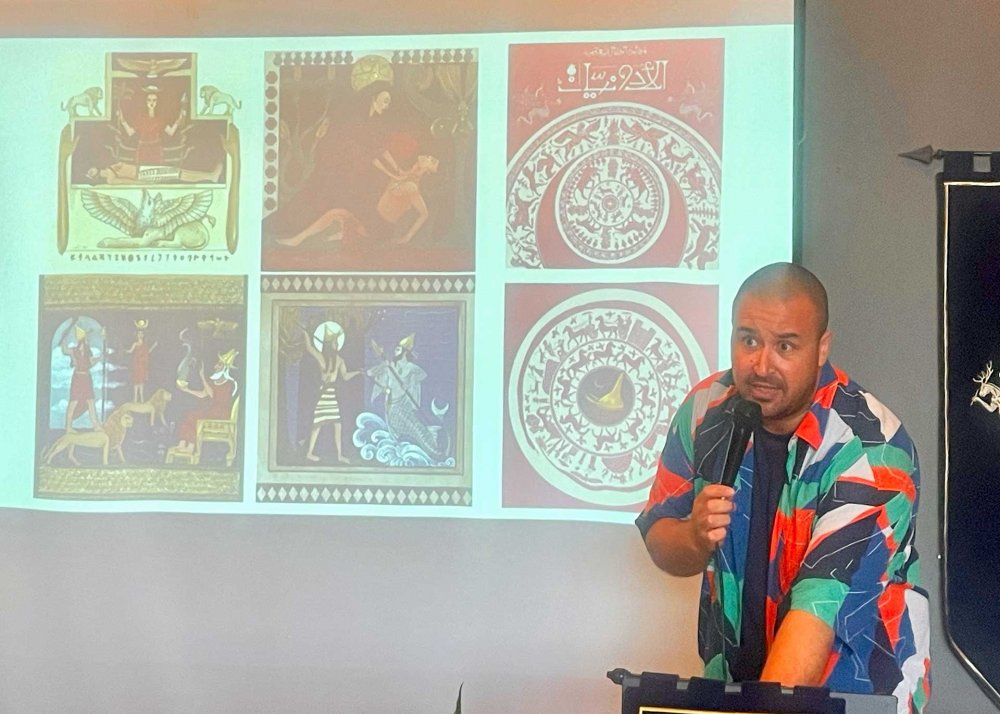

Jerusalem visual artist Ahmad Nabil has always been fascinated with the supernatural world. Ever since he was a child, he has had a vivid imagination, and he gravitated toward the enigmatic corners of the Old City of Jerusalem, where he found some intriguing accounts: People have told him their houses were haunted; random people have described the ghouls they saw roaming the streets of Jerusalem in detail. Throughout his curious work, he would come to realize that magic exists in Jerusalem, but this remains highly private and also frightening for many people, thus, it is a subject that people don’t talk about easily. For his sold-out book of illustrations and short scripts, Uns al-khafi (Hidden Companions), published in 2022, he interviewed 60 people and spent more than 35 hours gathering little-known legends of paranormal encounters with the unseen world in the city.