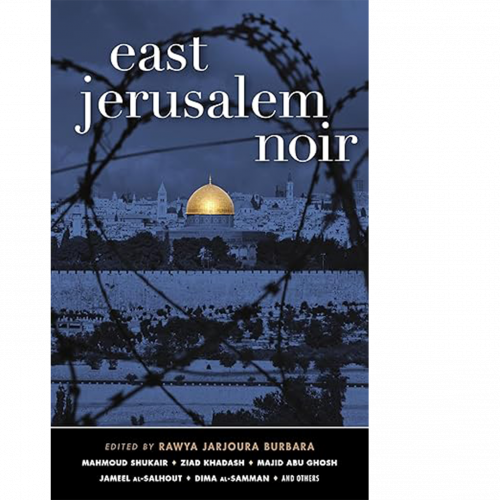

East Jerusalem Noir is a 2023 addition to the award-winning Akashic Noir book series. Each book in the series, which now includes over 120 titles, comprises a collection of original short stories set in a neighborhood or location of a distinct city. The contributors to East Jerusalem Noir are Palestinian and most are Jerusalemites; the anthology was published simultaneously with West Jerusalem Noir, a book composed of stories by Israeli authors.

The stories in East Jerusalem Noir are set in occupied East Jerusalem and, as one would expect from the series title, the stories are dark and foreboding, rooted as they are in the daily life of an oppressed population targeted by a hostile state. In the introduction, editor Rawya Jarjoura Burbara explains that compiling the stories in this volume was not an easy task. She described her vision for the book as follows: “to portray the city of Jerusalem as [the authors] live it, as they feel it, as they appreciate it, as they fear it, as they want it to be, and as they imagine it in the past, the present, and the future.”1

All the stories were written in Arabic and translated to English.

Part I of the book, “Fatal Crossings,” consists of five stories, and the first story of the section, “The Ceiling of the City” by Nuzha Abu Ghosh, sets the tone for the rest of the tales. It focuses on a Jerusalemite who aims to pray in al-Aqsa Mosque but is stopped by Israeli soldiers, found not to have his identification card, and carted off to jail, where he finds other Palestinians detained for various reasons. He is then released several hours later, but only after he is thoroughly humiliated by the experience. The demeaning treatment is compounded by his realization that he should try to hide his tears, “afraid they’d be captured in the cameras in the ceiling of the city.”2 This might sound like paranoia, but in fact it isn’t: In Nine Quarters of Jerusalem, Matthew Teller states that as many as 400 CCTV cameras maintain round the clock surveillance of the Old City.3

Two stories in this section are about families subjected to home demolitions. Ibrahim Jouhar’s “The Scorpion” recounts moments in the life of an unnamed man whose home is demolished early one morning by an Israeli scorpion bulldozer. The reason is never given—not even for the absence of a building permit—but perhaps that is the point: Israeli demolition of Palestinian homes is common, the pretext irrelevant. In fact, the Israeli bulldozer was demolishing other homes that same morning, one after the other. The man’s dreams are turned to rubble as thoroughly as the home in which he had imagined those dreams would come to fruition.

Rahaf al-Sa‘ad’s “In an Extraordinary City” has a similar theme but is slightly more elaborate: the home demolition order is associated with proximity to Israel’s Separation Wall, which wasn’t present when the house was built. The order was appealed but ultimately unsuccessfully, as the whole point of the legal shenanigans is to give the illusion that home demolitions are subject to a bona fide legal process and only undertaken when the circumstances are examined by sober legal minds. That process as a colonial tool of control becomes more obvious when the story’s characters discuss their choice between paying for the destruction of their home by the authorities or destroying it themselves. There is a casual savagery in this designed to strengthen the colonizers’ psychological grip on the native population.

Another tale, “Between the Two Jerusalems,” begins with the introduction of a character whose nickname, “the Hyena,” author Osama Alaysa wants to explore: who gave the young man with Down syndrome such a strange name. The young man is from the depopulated Palestinian village of Lifta, now in West Jerusalem, and the author goes on a delightful tangent to discuss the village before it was ethnically cleansed in 1948.

The Hyena found employment directing traffic in Ramallah, a Palestinian city located north of Jerusalem in the rest of the occupied West Bank. One day, a bored driver takes him to Jerusalem, where he tries to direct traffic, and the two “Jerusalems” meet. This creates a security issue, since the Hyena is wearing a Palestinian Authority (PA) uniform. The story ends with a swipe at the Israeli state and the PA in which the former is investigating the Hyena and the latter is roughing up the driver who took him to Jerusalem and then making the bruised driver sign a statement that he wasn’t roughed up. Mothers have the last word: When their sons want to emigrate, they remind them that “states and governments are bound by the laws of change and decay. However long they last, it is not forever.”4 One wonders how many young men are likely to cancel their breakout when hearing a sentiment that, while undoubtedly true, offers little consolation in the present.

The final story in the first section, “Fleeing from the Assyrian Soldiers” by Ziad Khaddash, is an account of a man in Jerusalem, which he describes as the most feminine of cities, whose actions follow the logic of a dream sequence. He is being hunted by soldiers for not having the right papers. This experience is familiar to most Palestinians these days who can never be sure that the Israeli official at the next checkpoint will let them pass. The unpredictability of checkpoints is surely their defining characteristic.

Part II is titled “Dreaming, Praying City.” It opens with Mahmoud Shukair’s story, “City of Love and Loss,” about a couple in love who must overcome family objections to their marriage. Social conventions, however, are not the only threats to their happiness; they also live in Jerusalem where home demolitions are ongoing, accidentally straying into settler territory carries significant risk, and water supply is intermittent. “Why can’t we enjoy periods of calm like other people do?” they both wonder. They try to console themselves with what they still have: “land, houses, memories, graveyards, and balconies. We forget ourselves if we forget them.”5

“An Astronaut in Jerusalem” by Iyad Shamasneh is about a child’s yearning to be an astronaut when he grows up and his slow realization that his aspiration cannot be realized when Israel occupies space completely. Even his personal space on earth, his home, is threatened by settlers who want to buy his family out. If it’s hard to dream big dreams in Jerusalem, it can also be hard to just do a conscientious job.

“Diary of a Jerusalem Teacher” by Rafiqa Othman recounts a schoolteacher’s commute to a West Jerusalem school for deaf children—what he sees and hears along the way that comforts him and what he experiences that makes him fear for his own security. The children’s drawings reflect their awareness of their belonging to a threatened group; the teacher’s interest in studying the drawings so that he can respond helpfully to the children in his care prompts him to take them home for more leisurely examination, which gets him into hot water when he is stopped and interrogated at the central bus station.

The last story in part II, “The Sun Still Shines” by Dima Al-Samman, opens with an exchange between a couple, Fares and Salma, and traces how they met, overcame class differences and family expectations, and eventually married. Fast-forward 35 years and their grandson is shot in the leg and then detained. Fares is by then a lawyer and able to secure his grandson’s release, but he is confined to his home. He learns to face his court-ordered restrictions with strength and determination. In that, he is like so many Jerusalem children who are forced to grow up sooner than they should have to.

Part III, “Moving into Despair,” comprises four stories that tap into some aspect of the Israeli web trapping Palestinian Jerusalemites as they try to do routine things, such as access health care and perform Friday prayers at al-Aqsa Mosque. Majid Abu Ghosh’s “This Is Jerusalem” describes Salim’s unsuccessful attempt to access urgent care when he wakes up one day with pain on his side. Unbeknownst to him, when he moved to the East Jerusalem neighborhood of Kufr ‘Aqab and then Israel built the Separation Wall, he lost his right to health care, an outcome that he learned about only when he needed the care. Referring to the pain in his side, Salim realizes, “far greater was the pain of oppression—the tyranny of oppression.”6 Here, Salim articulates explicitly what the rest of the stories hinted at implicitly.

Similarly, for devout Arabs, few things are more oppressive than being prevented from accessing a mosque at prayer time. In Muhammad Shuraim’s “Noble Sanctuary,” Hajja Aisha, a 75-year-old woman, travels to Jerusalem from Jordan so she can perform Friday prayers in al-Aqsa Mosque, but her plans are derailed by checkpoints, anxiety about whether she will make it in time, the detention of young men, and finally, tear gas.

Recalling how the landscape had changed since she lived in Jerusalem and how difficult it was to go anywhere, she is brought up to date by a fellow traveler who tells her by way of trying to calm her: “This happens all the time.” Oppression has become routinized, something to be expected.

The penultimate story in part III, “Mosques, Churches, Falafel, Mujaddara” by Jameel Al-Salhout, offers an almost comical account of a Palestinian man who takes his British journalist lover to visit his conservative family and her inability to grasp the significance of what she sees and hears. For example, upon learning he was born in a cave, her instinct is to visit and take pictures, until she learns that the cave is now located in a closed military zone. He gives her a tour of the Old City, but one senses that for a journalist, she knows little of the history and is only minimally interested in learning.

Nuzha Al-Ramlawi’s “Checkpoints of Death,” the last story, describes the chance encounter of two childhood friends who meet at a checkpoint after many years apart: Amani, who remained in Jerusalem, and Rita, who lives in the Palestinian diaspora.

Rita comes for a visit as a tourist, having lost her PA ID years ago. She is appalled by the changes wrought by Israel over the years, and she wanders, distraught, to an open space that natives know to avoid but which has no signs or warnings to advise the uninitiated.

There, while posing no conceivable threat to anyone, she is shot dead, “just another body beneath a numbered metal plate.”7

As a whole, the short stories in this anthology introduce readers to the lives of Palestinians who call Jerusalem home: their struggles to live a semi-normal life, the dangers that always lurk in the background, devised by a malevolent colonizer, and the city sights and sounds that sustain them and remind them of who they are and why they belong there.

Notes

Rawya Jarjoura Burbara, ed., East Jerusalem Noir (New York: Akashic Books, 2023), 14–15.

Page 23.

Matthew Teller, Nine Quarters of Jerusalem: A New Biography of the Old City (London: Profile Books; New York: Other Press, 2022), 10–11.

Page 48.

Page 99.

Page 149.

Page 193.