Introduction

Credit:

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division [LC-DIG-matpc-14445]

The West Side Story, Part 1: Jerusalem before “East” and “West”

Snapshot

For the period of Ottoman rule (1517–1917), and as it had been for centuries, Jerusalem was contained within the walls of the Old City. But with overcrowding and sanitation concerns rising, residents of the Old City began moving out of the city walls in the 19th century. What started as creeping suburbanization became an extension of the walled city called the New City. Neighborhoods like Talbiyya, Musrara, Qatamon, and al-Baq‘a were founded, designed, and built by Palestinians to reflect the sophisticated and Westernizing sensibilities of the city’s growing middle class, with modern infrastructure, palatial grandeur, and expert stonemasonry. Multiethnic, multinational, multilingual, and multi-confessional residents of the New City enjoyed ornate parks, state-of-the-art athletic facilities, secular and European school systems, modern cinemas and photography studios, as well as the luxuries and glamor that come with international and cosmopolitan city life.

Part 1 of a four-part series. View Part 2 here, Part 3 here, and Part 4 here.

In today’s Jerusalem, the part that is “West Jerusalem” is exclusively Jewish, and the mainstream narrative accepts this without question—that somehow “East Jerusalem” is the Arab side because it was annexed by Jordan for 19 years between the wars of 1948 and 1967. But the true story, glossed over and erased from Israeli and world public awareness, is that the area that is today called West Jerusalem had an entirely different origin and character, until it was violently and forcibly emptied and reincarnated between 1947 and 1950, and the years that followed.

Jerusalem’s Arab Palestinians were not always concentrated in its east side as they are today. Before 1948, Palestinians built and developed the emerging New City, including entire neighborhoods, and they enjoyed a cosmopolitan, bourgeois, even privileged urban life, living side by side with Jews and others.

Before, during, and after the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Palestinians were forced, or opted, to flee the large share of Jerusalem that later came under Israeli control and came to be known as West Jerusalem. They were also expelled from dozens of adjacent rural villages. They believed their absence would be temporary until the violence abated. However, Israel quickly set up legal mechanisms to ensure that they could not return or claim their property or assets, instead allowing the state to take possession of all of it.

A “total transfer”1 of Palestinians from West Jerusalem had been achieved; West Jerusalem was converted from a diverse and cosmopolitan urban center into an exclusively Jewish one. To this day, the state has not allowed Palestinians to return despite their deep historic roots in and around Jerusalem. Palestinians from the areas that became West Jerusalem—who numbered in the tens of thousands in 1948, as well as their descendants—cannot reclaim their families’ seized properties or assets, even if they live just a stone’s throw away in today’s East Jerusalem.

This part of the story is critical to reintegrate into the larger Jerusalem Story, because it remains an open, unresolved wound for Palestinian Jerusalemites, and because it informs our understanding of what the Israeli state intends with its geographic and demographic reengineering of East Jerusalem, which is an ongoing, massive effort.

This Backgrounder, Part 1 of a three-part series, explores the emergence and growth of the New City from the Old City and the fabric of life there before 1948. Part 2 takes a closer look at the city’s transformation under British Mandate rule and its eventual tumultuous slide into chaos, anarchy, and ultimately ethnic cleansing in the final years. Part 3 considers the process of erasing the New City and reincarnating it as Jewish West Jerusalem.

Jerusalem before There Was a “West” or an “East”

Before the Nakba (Catastrophe) of 1948, Jerusalem was not split into East and West. Rather, it consisted of the walled Old City and the New City, which had organically grown out of the Old City in the 19th century, mainly to the west and the north. Before the Nakba, these neighborhoods were home to multiethnic Jews, Muslims, and Christians, as well as a sizable number of foreigners.2

The origin and emergence of the New City

Jerusalem began to grow out of its original walled Old City from the mid-19th century until after the 1948 War3 and the subsequent ceasefire and armistice agreements in 1949.4 The expanding population, overcrowding, and sanitation problems in the Old City, as well as the growing sense of security outside the walls, encouraged residents to purchase property or land outside of the walls of the Old City.

According to Jacob Nammar, whose family established one of these early neighborhoods (Haret al-Namamra), the decision to venture outside the Old City walls “was a bold undertaking, since the land was barren, uninhabited, and filled with danger from robbers and wild animals.”5 Gradually, the image of living outside the city walls transformed from one of remote isolation into one of comfort and community.

The Ottoman land reforms of 1839 and 1856 allowed non-Ottoman citizens to own properties and land in Palestine. These reforms, together with European strategies for increasing European presence6 and enforcing “religious-cultural penetration” of the holy places in Palestine,7 especially in Jerusalem, formed a fertile ground for external land purchases by non-Ottomans. Jewish philanthropic societies and later Zionist organizations also took advantage of these reforms. Thus, most of the New City landowners consisted of Arab Palestinian villagers, churches, or wealthy families or individuals.

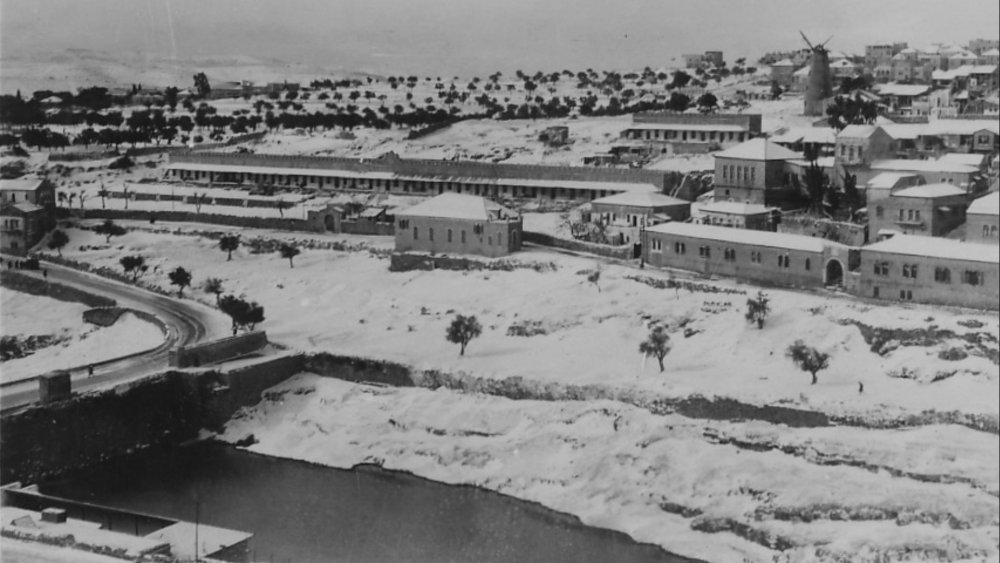

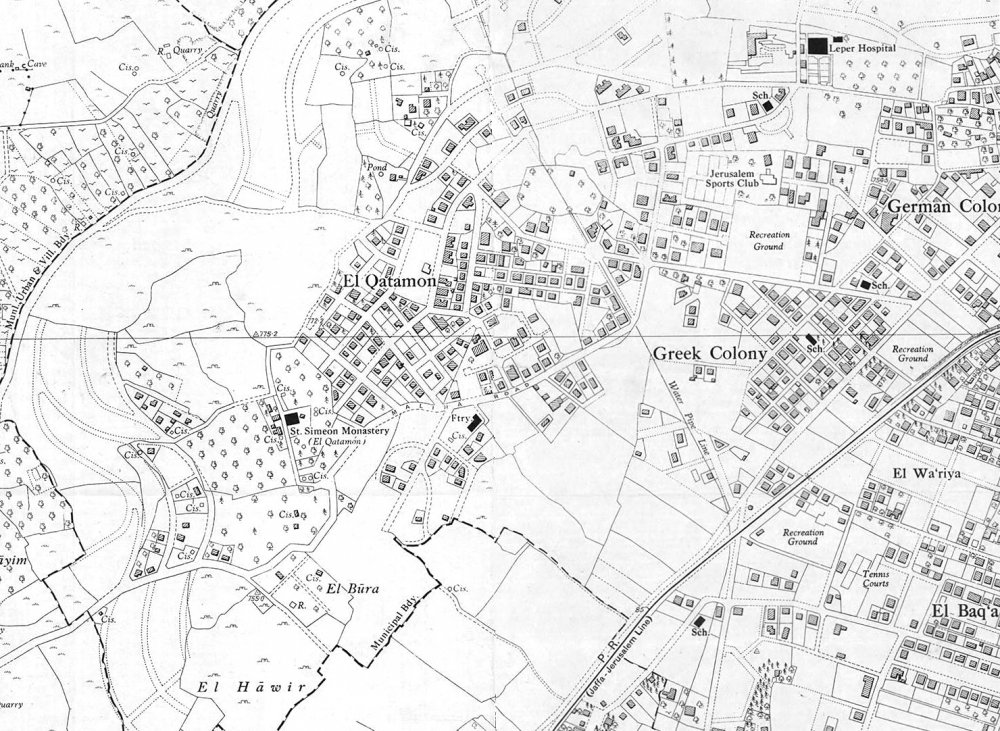

Documentation of growth

Overall, evidence of the New City’s expansion from the late Ottoman to the early Mandate periods is problematic, since many of these maps were made by foreigners who focused more on Christian missionary activity in their Jerusalem cartography. The Jewish and Christian land purchases and construction projects in both the Ottoman and the British Mandate periods, however, were well documented.8

Although the New City’s land titles were only partly recorded in the land registry during this period, land tax records provide a clear picture of land ownership. According to David Yellin, an educator, researcher, and politician from Jerusalem, in 1900, “The total number of new homeowners [in the New City] amounts to 111. Of these, 56 are Jews, 27 Christians and 27 Muslims.” He goes on to list the values of the properties, as well as the proportion of wealthy homeowners within each confession: “Among the Christians, the proportion of wealthy builders is 54 percent; among the Muslims 33 percent; and among the Jews, only 12 percent.”9 It is clear that members of each confession saw value in purchasing lands and building properties outside the Old City walls.

Jewish and Arab migration to the New City

The first Jewish settlement outside the walls was Mishkenot Sha’ananim in 1860. From the very start, it had walls and gates that locked at night to entice people to move from the Old City. Later, this became part of the Yemin Moshe neighborhood.

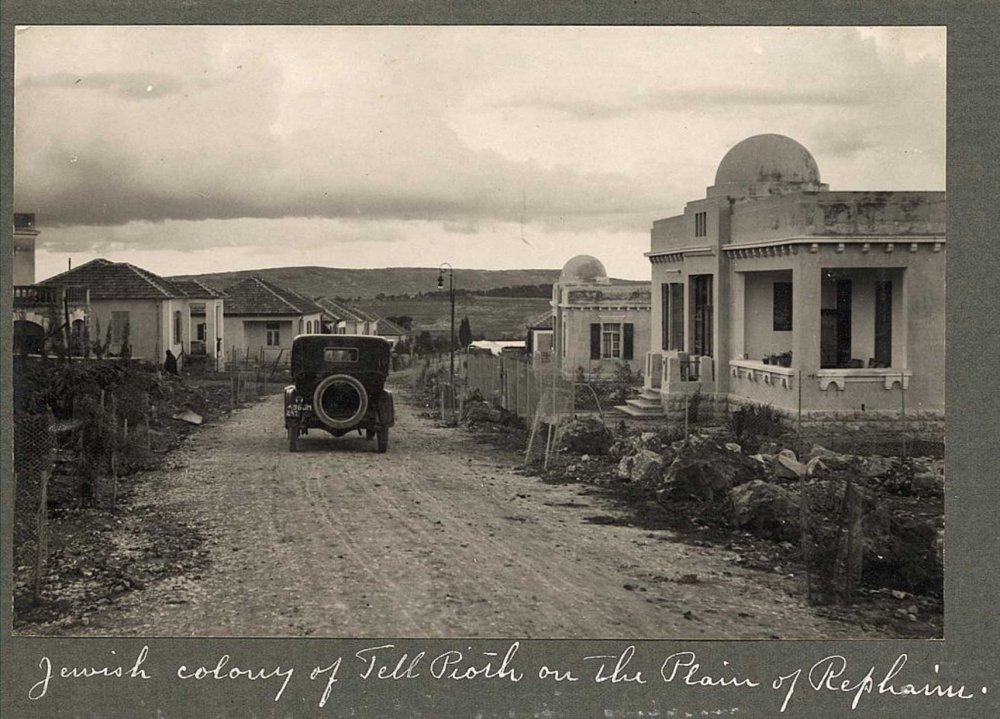

Movement of the Jewish population outside the walls started picking up after the 1860s, particularly in the late 1880s, as increasing numbers of Jewish refugees settled in the city, most of whom were fleeing pogroms in Eastern Europe, and became enticed by Zionist propaganda related to settling Palestine.10 Before 1948, Jews who were part of the Jewish Yishuv11 chose to establish some of their new Jerusalem suburbs to the west and northwest of the Old City.12 The Jewish population of the New City included a large number of poor and working-class people.13

Detailed records of these Jewish neighborhoods were kept by Jewish (and later, Zionist) societies and philanthropic organizations and their funders in order to document settlement plans. An examination of these records yields insight into the structural plans of Zionist settlement in and around Jerusalem. By design and intention, these Jewish areas were often planned to be self-standing “communities” that were separate from their surroundings:

The separation between Jews and Arabs originated with the renewal of Jewish settlement in Palestine at the end of the 19th century; that is, the beginning of Zionist activity in the country. It was caused not only by the wide gulf between the two populations, but was also largely the result of intentional and conscious activity on the part of the Jews, who aspired to live apart from the Arab population. In mixed cities, Jews resided mostly in their own quarters and neighborhoods; while the new settlements founded by Jews, both urban and agricultural, were made up of Jews only. From the very beginning of the Mandate period, the Jews built their own political institutions to advance their autonomy, with the aspiration for full independence. In short, the Yishuv had a clear self-perception of being a distinct and separate entity and it acted on both the political and the practical levels to make this vision real.14

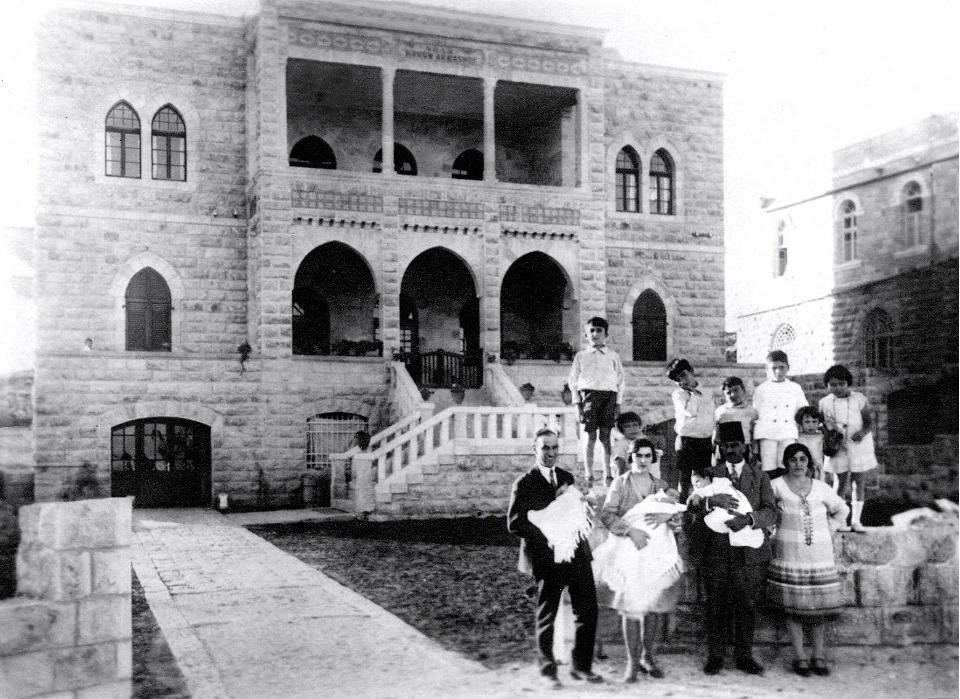

By contrast, the movement of Arabs into the New City, like that of the Armenian and Greek families who also moved there, was mostly driven by wealth, family capital, and individual capacity. Most families who could afford the move on their own were middle or upper class. Since their investments were mostly of a personal nature, this process was not always officially documented. The homes they built were largely private homes, not inclusive communities.

According to local cartographer Khalil Toufakji, director of the Maps and Survey Department at the Arab Studies Society in Jerusalem, historically, Christian Palestinians started building and expanding outside the Old City’s southern and western boundaries closer to Bethlehem. In these areas, the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate owned most of the land, and it began selling off plots of land when it came under financial stress after World War I and the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, which meant Russian pilgrims were no longer allowed to make pilgrimages to the Holy Land, incurring the Patriarchate considerable losses.15

One of those new neighborhoods was Qatamon. Development plans for Qatamon were submitted to the authorities in the early 1920s; homes began going up in 1927.16 Ghada Karmi, a Palestinian Jerusalemite, describes the neighborhood where she grew up: “We lived in al-Qatamon, a handsome suburb in west Jerusalem, mostly inhabited by well-to-do Christian Palestinians and a minority of Muslims like us.”17

The location of Muslim families in the New City was dictated by their capital. The less wealthy Muslim Nammar and Wa‘ari families, for example, were among the first to move outside the city and established their homesteads in Lower Baq‘a. In the 1870s, the Nammar family purchased land from the villagers of al-Maliha, Beit Jala, and Bethlehem. In his autobiography, their descendant Jacob Nammar writes that Haret al-Namamra, a quarter in al-Baq‘a,

originated from the efforts of the pioneer family of Abdullah Ibrahim Nammari, whose five boys and girls built their own homes in the neighborhood. This tradition continued to evolve and grow over the years as cousins moved in, followed by other members of the extended family—including ours—which created a vibrant neighborhood.18

Soon, the quarter was called Haret al-Nammara after the family name.

In the late 1920s, the family even established a market in the Nimamri corridor called Suq al-Namamra, which served both the local neighborhoods of the New City and the neighboring villages.

The Wa‘aris—so named because they left the Old City and moved to the wa‘ar, or wild countryside—had prevailed on the Governor of Jerusalem in the 1870s to grant them government land in Lower Baq‘a, which they then registered as family property. Soon, their quarter, which grew into a residential suburb that was nestled among orchards and crops, was called al-Wa‘ariyya after the family’s name.19

The more established Muslim families like the Husseinis, Nashashibis, and the Khatib clan built their residences in the neighborhoods north of the Old City. These houses used luxurious stone from the nearby village of Deir Yasin that was distinguished by its pure white color and rough-hewn texture. Thus, alongside the expansion to the west, Jerusalem witnessed another expansion in the northeast toward the neighborhoods of Wadi al-Joz, Sheikh Jarrah, and al-Tur.

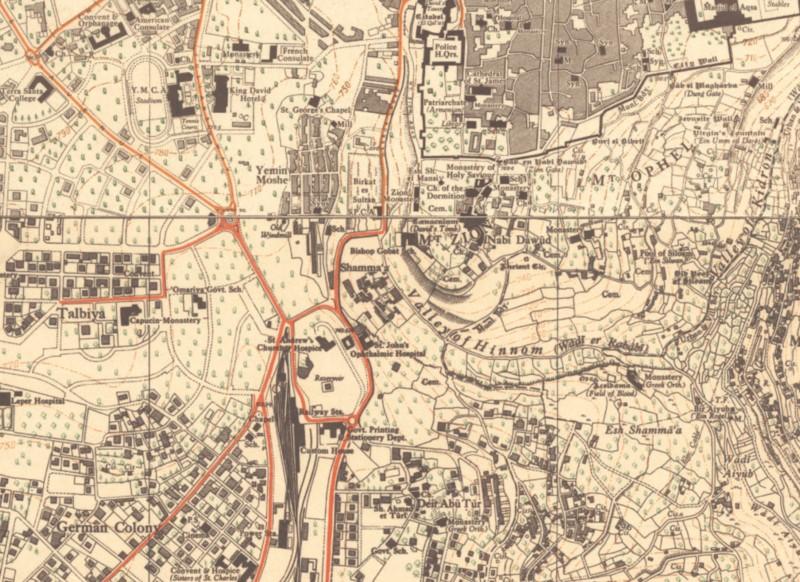

The New City’s Palestinian Arab neighborhoods

Over time, distinct Palestinian Arab neighborhoods emerged in the New City, most of which were built during the British Mandate in the 1920s and 1930s. While the Arab notables and ashraf20 lived in Sheikh Jarrah and Wadi al-Joz, neighborhoods to the northeast of the Old City, the new Arab middle classes began to move in the late 1920s to the bourgeois, southwestern suburbs of Qatamon, Talbiyya, and al-Baq‘a. Al-Baq‘a was further divided into Baq‘a al-Fawqa (Upper Baq‘a) and Baq‘a al-Tahta (Lower Baq‘a).

Arab Talbiyya and Jewish Rehavia were founded and developed side by side, beginning in the 1920s.21 According to a development map of the built-up area in Jerusalem, about half of the houses in the Qatamon neighborhood were built between 1927 and 1937, and the other half between 1938 and 1948.22 One study found that:

by the 1940s, there were well over 100 buildings in Qatamon, including private villas, two- and three-storey apartment buildings offering flats for rent, and shops—grocers, a telegraph office, a bakery and butcher shop, and even an ice factory. There were also three hotels and several foreign consulates, including those of Iraq, Egypt, Italy, Poland, and Czechoslovakia.23

In his memoir, Out of Place, Edward Said wrote:

My distinct recollection of Talbiyah, Katamon, and Upper and Lower Baq’a from my earliest days there until my last [in December 1947] was that they seemed to be populated exclusively by Palestinians, most of whom my family knew and whose names still ring familiarly in my ears—Salameh, Dajani, Awad, Khidr, Badour, David, Jamal, Baramki, Shammas, Tannous, Qobein—all of whom became refugees.24

The New City became a place for Arab residents to reflect their wealth in the architectural designs of their properties and gardens in a way that they had been unable to do in the crowded Old City. Jacob Nammar remembers:

[In] Haret al-Namamreh . . . They built palatial homes with unique, spacious architectural designs including arched doorways, tiled floors, high ceilings, and large windows for an upper-class lifestyle. These qusur, or villas, were built from carved limestone with large cream and pure white stones that kept them warm in winter and cool in summer. The red tiled roofs, which shone beautifully at sunset on the hilltop, stood next to each other on both sides of a straight line which became known as the Share’a al-Namamreh—Namamreh Street.25

The old buildings and homes in what is today West Jerusalem reflect the development of Jerusalem’s wealthy Arab families—prestigious stone palaces built in a style that integrates the features of Islamic and modern architecture. They are characterized by a rare aesthetic and scale: the arches are their distinctive sign, and there is a garden in front of every building planted with lemon and pomegranate trees, and jasmine.26

Hala Sakakini lived in the neighborhood of Qatamon with her family. As she and her esteemed father, Khalil Sakakini, were both prolific diarists, they left a firsthand record of what life was like there. Their own two-story house was completed in May 1937, designed according to their own specifications and built under their watchful eyes for the year prior:

In comparison to the luxurious villas built on Qatamon’s streets during the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s in the Eclectic and International styles, the Sakakinis’ house was simple and modest, architecturally based on straight lines and devoid of pomposity and monumentality. There were no arches carried on Corinthian columns, or grand flights of stairs at the house’s entrance, as in some of the houses in the neighbourhood. Many of Qatamon’s buildings tended towards the spectacular, yet this effect of grandeur was achieved in different ways. The houses were distinctive in their overall design but also in their minutest details: the type of stone used, the shape of the roof, even the colour of the iron shutters at the windows. Most of the buildings had vast gardens with various trees and bushes decorating them.

In a way, Qatamon’s houses functioned as display windows for their owners’ credos, lifestyle and preferences. Hala Sakakini summarized it eloquently when commenting: “[E]very house had individuality; somehow it was marked by the personality of its owner.” In this sense, the quarter’s affluent residency was transcended through its garden-suburb planning and architecture: that of an elitist bourgeois community of well-educated and mostly secular Arab-Christians (mainly Greek-Orthodox, but also Catholics, Protestants, Armenians and Muslims) who followed a cosmopolitan lifestyle.27

Those who wanted to show their wealth were not only satisfied with one lavish palace, but even bought property and erected a neighborhood corridor. The home of the late Palestinian businessman Constantine Salameh was one of these. “Villa Salameh,” as it was called, is considered “one of the architectural masterpieces of the city.” Designed by the famous French architect Marciel Favier in 1935, the house

is based on the “liwan plan,” which in Arab dwellings refers to the all-important central room that gives access to other, lesser rooms. Thus, the entrance of Villa Salameh leads to a double-height central hall, in the center of which is a marble octagonal fountain, from which other rooms branch off. On one side of the large hall is a wood-paneled dining room, next to which is the salon, or living room. A service elevator connects the dining room to the basement, which contained a kitchen, wine cellar, laundry room, servants’ quarters, storerooms and a two-car garage.

An internal elevator connects the ground floor with the two upper floors. Each of the bedrooms has its own bathroom, in Italian marble. The door handles, accouterments and the decorations, including the lamps and the wood furniture, are all in art deco style and, along with every item in the villa, were all designed by the architect himself.28

The letters CS are engraved above the door to this day.

Salameh owned three buildings surrounding a square that was named after him, “Salameh Square” (now called Orde Wingate Square).29 And these were just a small portion of his vast property holdings throughout the country, all of which were left behind when he and his family “left Jerusalem in the midst of the fighting that raged in the city in 1948. They were compelled to leave the house in Talbieh because of the shooting and shelling, in which relatives and friends were killed. They had no choice but to leave, and the departure was an extremely sad event for them.”30 They were among the last to leave the neighborhood on March 13, 1948, but Salameh left his key with the Belgian consul and leased the home to him. His home, which was seized by the Israeli state, still serves as the residence of the Belgian consul general today.

But the Palestinian origins of these neighborhoods goes beyond architecture. Before their exile in 1948, Palestinians in the New City were responsible for much of its ethnic, religious, and socioeconomic diversity. With the establishment of the new neighborhoods, wealthy Arabs also started investing in constructing apartment buildings and renting them out to less wealthy Arabs and Jews who wanted to escape the Old City but did not have the means. Thus, with time, the New City witnessed changes in socioeconomic status and a diversity in ethnicity and religion.

What is more, the New City became home not only to diverse communities in majestic houses, but also to a social fabric made up of a range of familial and communal relationships that are preserved in the memories and stories of the neighborhoods’ original inhabitants. Palestinians who grew up in these neighborhoods recall an idyllic childhood in a lush surrounding that was as much part of their daily lives as their homes, families, and schools. Jamil Toubbeh writes:

Palestinian families living in Qatamon January 1948

| Family Name | Number |

|---|---|

| ’Abdeen Salah Husseini | 1 |

| Jawharieh | 1 |

| Lorenzo Albina | 1 |

| Mouchabeck Kourt Antoinnete Sliheet Theodori | 1 |

| ’Arnous Kreitem Mansour | 1 |

| Sfeir | 1 |

| ’Awi Baddoor Kassicieh | 1 |

| Khoury | 1 |

| Telegraph Seniora Beida | 1 |

| Oweida | 1 |

| Mnatzagenian Budeiri | 1 |

| Christo Theodori | 2 |

| Joury Dabbah | 1 |

| Munah Touqan Zu’rob Kar’a Farraj | 2 |

| Joury Dabbah | 1 |

| Muna Touqan Zu’rob Kar’a Farraj | 2 |

| Sweida Farraj | 1 |

| Ruheimeh Hamarneh ’Abdo Nuzha Sukkab Mansour | 2 |

| Harami Antipas Houmsi Toubbeh | 1 |

| Husseini | 2 |

| Shaheen Batchon Kharouf Husseini | 3 |

| ’Arnita Nammari Jawahrieh | 2 |

| Tleel | 1 |

| Nuseibeh Jawharieh | 3 |

| Fityani Jme’an Shtakleff | 1 |

| Jouzeh | 1 |

| Haddad | 3 |

| Kamar | 1 |

| Tleel | 2 |

| Farah Kassicieh | 2 |

| Nalpantian Tobbeh | 2 |

| Shtakleff | 2 |

| Kavalkanti George Kawar | 2 |

| Beida | 2 |

| Khoury | 2 |

| Abu Jaroor Husseini | 4 |

| Khoury | 3 |

| Jouzeh | 2 |

| Sfeir | 2 |

| Ajrab Laidi Bazouzi Shamieh Louisides Albina | 2 |

| Ma’mari Doumaniani Kassicieh | 3 |

| Taji Husseini | 5 |

| Farraj | 3 |

| Arda’ji Moughar Dabbah | 2 |

| Muhtady Murcos Zananiri Totah Kandalaft Nassar Khalidi Oweida | 2 |

| Papdoulous Rizek Sakakini ’Awad | 1 |

| Miaeledes Shahabi Hannah Khasho Budeiri | 2 |

| Sruji Kawar | 1 |

| Tata Da’des Awad | 2 |

| Theodori | 3 |

| Kamar | 2 |

| Muchahwar Toubbeh | 3 |

| Wahneh Kassicieh | 4 |

| Friej | 2 |

Notes

Toubbeh, Day of the Long Night, 16.

The names of the Palestinian families who resided in Qatamon until 1948 are as follows:

As children in [Qatamon in] the late 1930s and 1940s, we had disappeared into horizons of wheat fields, vineyards, fruit orchards, or railroad tracks and then, like bees guided by internal sextants, had headed home in time for dinner.31

Hala Sakakini noted in her journal:

The new [pre-1948] residential areas in the southern part of the city—Talbieh, Nammara, Katamon and Lower Baq’a—were the fashionable Arab quarters. Together they formed a garden city, as they consisted mainly of villas surrounded by gardens. All houses, almost without exception, were built of stone, and the largest were two-storey four-apartment buildings. A simple, modern architectural style was prevalent in the residential areas, yet every house had individuality; somehow it was marked by the personality of its owner.

The majority of the houses were built of beige or greyish stone, but among them there were quite a number of beautiful pink stone. Skillful masonry was often manifest in the way the stones were arranged around the windows and doors and over the verandas.

Many of the one-storey villas had red-tiled sloping roofs. The colour of the iron shutters at the windows provided a pleasant variety; the greyish houses usually had dark green shutters, the beige houses creamish ones and the pink houses black ones. Individual taste was also shown in the iron bars at the windows and in the banisters. In general these were simple, but here and there one could notice intricate, beautifully wrought designs, something like lattice work.32

Jacob Nammar wrote:

I loved the house [in Haret al-Namamra] where I was born. The front yard was spacious, with a large vegetable garden and many fruit trees planted by my grandfather, uncle, and Baba. We had figs, pine, saber (fruiting cactus), grapevines, and mulberry trees. In one corner of the yard we raised pigeons, chickens, rabbits, and sometimes sheep that Baba kept. Our home, like others in the neighborhood, had a well that stored the rain for our consumption. We were never hungry; food was in abundance. During spring, at dawn, one could find us on top of the mulberry tree eating the fruit, competing with the many local birds. Mother would wash everyone’s mouth and red-stained hands, as she disapproved of our excessive eating.33

And Edward Said recalled:

Our family home was in Talbiyah, a part of [what became] West Jerusalem that was sparsely inhabited but had been built and lived in exclusively by Palestinian Christians like us: the house was an imposing two-storey stone villa with lots of rooms and a handsome garden in which my two youngest cousins, my sisters, and I would play. There was no neighborhood to speak of, although we knew everyone else in the as yet not clearly defined district. In front of the house lay an empty rectangular space where I rode my bike or played. There were no immediate neighbors, although about five hundred yards away sat a row of similar villas where my cousins’ friends lived.34

The homes were but one facet of cosmopolitan life in the New City. According to one study of the Sakakini house:

In a way, Qatamon’s houses functioned as display windows for their owners’ credos, lifestyle and preferences . . . In this sense, the quarter’s affluent residency was transcended through its garden-suburb planning and architecture: that of an elitist bourgeois community of well-educated and mostly secular Arab-Christians (mainly Greek-Orthodox, but also Catholics, Protestants, Armenians and Muslims) who followed a cosmopolitan lifestyle. Among them were intellectuals such as the poet Fadwa Tuqan and the land scholar Sami Hadawi. They were joined by families of British and Jewish civil servants and British army officers, as well as foreign diplomats. The high standard of living included private schooling conducted in European languages, swimming lessons, lectures and concerts at the nearby YMCA, and consumption of fashion imported from or bought abroad. At the same time, local eastern traditions, language and culture were maintained—the men covering their heads with tarbush and smoking nargila, for example.35

In addition to the aforementioned, the New City’s Arab neighborhoods included Musrara, Sheikh Jarrah, al-Nabi Daoud, al-Dajaniyya, Mamilla (Ma’min Allah in Arabic), the Ratisbonne, and al-Thoury (Abu Tur). Some of these original New City neighborhoods, especially those to the north, like Sheikh Jarrah, ended up in what became East Jerusalem after the 1948 War.

Other notable New City neighborhoods

The German Colony was founded by German Templars in the New City to establish what they viewed as the ideal Christian community in the Holy Land. The Templars were a breakaway community of German Protestants who first migrated to Palestine (Haifa, to start) in 1869 to build a spiritual community in the belief that this would hasten the Second Coming of Christ. Starting in Haifa, they went on to found seven Templar colonies across Palestine between 1869 and 1906.

Their settlement in Jerusalem began in 1873, about a decade before Jewish-Zionist immigration got underway, and they were very industrious in clearing land, establishing communities, and building homes and institutions, including schools.36 Muslim and Christian Arab families found themselves buying and renting property in this part of the city. The Sakakini family, for example, rented a house in the German Colony neighborhood, and their children attended the German school there. Rosemarie Hahn, who was born in the German Colony in 1928, recalled how diverse her school—possibly even the same one—initially was:

I have only happy memories . . . For us as children it was like living in our own homeland—we didn’t know anything else. We were friends with everybody—my best friends in kindergarten were a Jewish girl and an Arab girl. English, Jewish, Arab, Armenian—everybody was accepted into our school.

But that changed after 1934. My Jewish friend was taken out of school, and my brother had a Jewish friend who never came back—because of the politics. The Greek Colony, adjacent to the German Colony, was another New City neighborhood that emerged during this time, through the extensive land acquisition activities of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate. Like other Christian churches that began investing in Palestine from the 1830s onwards, the Greek Patriarchate, the oldest and largest Christian church in Jerusalem which also had various advantages over other churches in land acquisition, bought vast amounts of land and property throughout Palestine, including Jerusalem, starting in the nineteenth century.37

In the specific case of the Greek Colony, in 1900, a monk named Abtimos purchased 1,000 dunums of land south of Jerusalem near Qatamon, which was then developed into the Greek Colony, a neighborhood originally designed to serve the Greek Orthodox population of the city.38 The first 20 homes were designed and built by a Greek architect, as well as a community center called the Greek Club, which was completed in 1902. This club became a hub of the Greek community’s activity, including celebrations of holidays and feast days, until 1948.

The Greek Colony and other upscale New City neighborhoods were largely mixed, neither Jewish nor Arab, and were home to ethnically and religiously diverse residents. In some neighborhoods such as Qatamon, this also included British and Jewish civil servants, British army officers, and foreign diplomats.39

The City’s Rural Hinterland

In addition to the neighborhoods located within the New City, approximately 40 nearby Arab villages and hamlets fell within the greater Jerusalem District to the west of the city, such as Deir Yasin, ‘Ayn Karim, al-Maliha, and Lifta.40 Although they did not have formal municipal ties to the city, these villages were a fundamental part of Jerusalem’s daily life and its economic web, and they linked Jerusalem to other major cities in the country.41

From the early 1920s, with the construction of the neighborhoods of the New City, these Arab villages had a huge impact on the city’s political and social life. Residents of these villages lived so close that they walked from their villages every day to their places of work in the New City.42

By 1929, Jerusalem had absorbed the surrounding localities and villages of Lifta, ‘Ayn Karim, al-Maliha, and Deir Yasin, and this absorption contributed to the evolution of social relations and politics.43 Many women and men came from the surrounding villages to work in the city in wealthier families’ homes, including serving as housekeepers, babysitters, and gardeners. In her autobiography, In Search of Fatima, Ghada Karmi describes Fatima al-Basha, a woman from the village of al-Maliha who cooked, cleaned, and took care of the family home while helping raise the children. Karmi describes her feelings towards Fatima as “motherly.”44

These special connections between Jerusalem’s Palestinians and nearby villagers extended beyond the city limits. The ancient village of Battir, located southwest of al-Maliha on the outskirts of Beit Jala and al-Walaja, was a favorite destination for many New City residents. Jacob Nammar shared stories about his family’s relationship with Battir:

In Palestine there were once over twelve hundred villages scattered throughout the mountains and the countryside, some dating back two to four thousand years. The villagers belonged to the land and were connected to it, physically and spiritually. The shepherds, artisans, and farmers who formed the “bread basket” proudly fed the entire country for many years.

Each village was unique, laced with terraced hills that covered the landscape, evidence of a prosperous agricultural history with abundant cultivation of grapes, apples, pears, figs, almonds, pistachios, walnuts, olives, oranges, and many beautiful flowers and vegetable gardens. The richness of village culture was exemplified by the beautiful village of Battir, which blended with the country scene that lay eight kilometers southwest of al-Quds, in the mountains, next to the al-Quds-Jaffa railroad.

My family’s first connection to Battir was inspired by my sister Fahima. The French nuns at Saint Joseph school raised rabbits for their consumption, a French custom. So on the way to school each morning, Fahima would stop at the produce market to pick up scraps of radish leaves, lettuce, and other vegetables to feed the small creatures. As a result, Fahima became good friends with a wonderful fellaha (female farmer) named Fatima ‘Alayan from the village of Battir who came early each morning to sell her produce. This friendship grew as Mama invited Fatima to our home and gave her hand-me-down clothes. Our families became good friends and found common interests. On Saturdays she would come to help mother hand wash the huge pile of clothes and hang them outside on the clothesline to dry . . . On holidays and summer vacations, we reciprocated by visiting Battir, a fifteen-minute train ride in the boxcars, which were free for the fellahin.

By the early 1940s, most of the southwestern suburbs of the New City extended to the boundaries of the nearby villages, including Lifta, Deir Yasin, al-Maliha, and ‘Ayn Karim.

Industrial and Spatial Growth Fueled by Modernization

The growth of the New City was fueled by key modernization projects which began in the late Ottoman period and continued through the British Mandate.

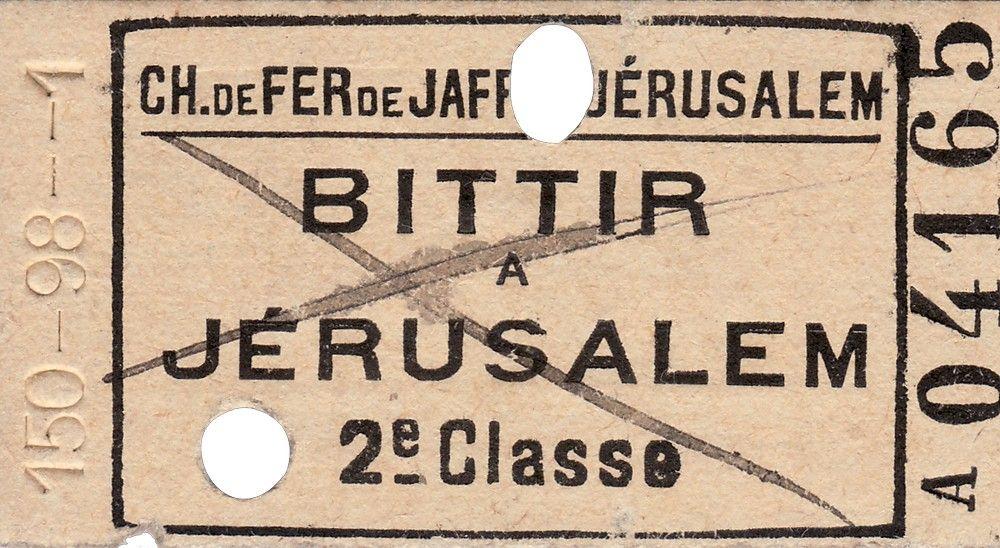

Jaffa-Jerusalem railway

In the mid-19th century, during Ottoman rule, various developers and engineers repeatedly attempted to build a railroad in Palestine, until it was finally completed in 1892. The Jaffa-Jerusalem railway was the first railway to be built in Palestine. Although others had previously envisioned and attempted to realize the project, the railway was finally completed by a Jewish Jerusalemite, Joseph Navon, who raised funding from the French Société du Chemin de Fer Ottoman de Jaffa à Jérusalem et Prolongements. It was funded and managed by the French, and used American trains, connecting Jerusalem (the main site of pilgrimage) to Jaffa (the main port city where pilgrims of all faiths arrived in the country).

Previously, this journey along the coast and then through the steep hills on Jerusalem’s western side would have taken three days to walk or ride on an animal’s back. Now, the journey over the selected route of 86.5 kilometers45 was reduced to 3.5 hours,46 which opened Jerusalem to a far greater influx of foreigners arriving through the port at Jaffa, and brought them with ease from the coast to the Holy City, 2,480 feet above their starting point in Jaffa.

While European developers and funders wanted the train station in Jerusalem to be built closer to the holy sites, the Ottoman administration wanted to keep Europeans and other foreigners outside of the walled city. Thus, it insisted on building the Jerusalem station in the New City neighborhood of al-Baq‘a. It was situated on less than nine acres of land bought from the Greek Convent for $25,000, located close to the German Colony.47 From the station, travelers would take a carriage to Jaffa Gate in the Old City.

The station formally opened on September 26, 1892, although the first train made the full journey on August 27. The railroad opened with seven stations—Jaffa, Lydda, Ramleh, Sajad, Deir-Aban (Monastery), Battir, and Jerusalem. A planned eighth station at al-Walaja, just before Jerusalem, was never completed.48

The railway ran once a day in each direction. First-class round-trip tickets sold for 4 dollars, while second- and third-class tickets cost 33 cents. Most first-class tickets were sold to wealthy locals, while pilgrims bought the cheaper tickets. On Sundays, the train would take well-to-do Jerusalemites and foreigners from the station in al-Baq‘a to the nearby village of Battir to see the ancient irrigation system and picturesque terraces.49

The building of the railroad, and the more expansive Hijaz railroad that connected northern Palestine with other sites in the Levant all the way south to the Islamic cities of Medina and Mecca, and which officially opened in 1908, stimulated intense competition between Europeans in purchasing land, building institutions and churches, and bringing Christian pilgrims to Jerusalem. The German community in the German Colony neighborhood was one of the beneficiaries, as it built its colony in al-Baq‘a, near the train station. Once the work on the railway began, the value of properties in the vicinity of the railway and its stations rose dramatically. For example, a plot of land near the Jaffa station was sold for $20,000, after it was purchased for $1,300 before the railway.50

The railroad also triggered a short-term population boom. One report written in The Railway Magazine in 1902 says that the city’s population increased from 30,000, when the station opened in 1892, to 55,000 10 years later.51

The railroad also helped battle the water shortage in Jerusalem, especially during summertime, as the trains started delivering drinking water from the al-Haniyya fountain (Philip’s Fountain) in the village of al-Walaja near Beit Jala to the south. Soon, the train station in al-Baq‘a transformed into a water-selling spot for middle- and upper-class Jerusalemites and foreign residents.52 And it made possible the opening of a municipal hospital in 1891, with free access to all Jerusalemites.53

After the British Mandate was established in 1920, and following the announcement of the establishment of Palestine Railways on October 1, 1920, the British widened the railway to 143 cm and purchased it from the French for £565,000.54 The Jaffa-Jerusalem railroad continued to operate under different regimes and then ceased to function altogether in 1998.55

Roads from elsewhere

During the late Ottoman period, highways and roads were paved to connect Jerusalem to Jaffa, Ramallah, Nablus, Hebron, and other cities, thus encouraging the city’s economic and demographic growth.

Public space, public time in the city

Starting in the 1890s, the Ottoman administration and local Palestinian authorities undertook a sweeping set of projects meant to urbanize the city and link the fledgling New City with the walled Old City by means of a new municipal quarter at Jaffa Gate, which had become the city’s most important gate. This effort began with the opening of the New Gate (1889) to link the Christian Quarter and the new neighborhoods emerging to the west of the city, the construction of urban and inner-city roads to improve traffic flow, a municipal hospital (1891), a public park and municipal café (1892), a new city hall (1896), a public fountain (1900), and the famed grand clock tower at Jaffa Gate (1907).56

The clock was one of seven built throughout the country and 100 built throughout the Ottoman Empire to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the rule of Sultan Abdul Hamid II. It stood 13 feet high and had four clock faces, one facing each direction. Historian Vincent Lemire tells us that the clock tower gave out light in all directions and was visible from far-off villages:

Intended to signify Jerusalem’s new centrality in its surroundings, the clock tower showed itself in all its modernity, standing as a public monument free of any religious interpretation. Like a municipal belfry, it was the first “urban” monument of the holy city, and it placed Jerusalem within a global temporality, resonating with the great cities of the world at that time, such as Paris and the tower of the Gare de Lyon.57

But the clock signified something more as well:

Up to that time, each religious community had referred to its own world of sound to construct its own temporality (the muezzin for Muslims, the shofar for Jews, bells for Christians); the clock at the Jaffa Gate henceforth provided secularized hours for all, a public time that, like the public space that was invented at the same moment, enabled urban dwellers to move within a shared urbanness. It was no accident that this new public time ticked at the Jaffa Gate, in the heart of what the Jerusalem Chamber of Commerce called “the business quarter”—a neutral space, inclusive and open to all, within which all the segments of the urban community encountered each other.58

Other enhancements included the “sarayas (government house), mosques, public parks, educational and cultural institutes . . . and a museum of antiquities in Jerusalem.”59 To the north of the Old City, an impressive octagonal structure was built to house the new Rockefeller Museum of Archeology.60 The authorities also installed the telegraph line in 1865 and built Ottoman postal branches in Jerusalem and Jaffa.61

During the British Mandate, the New City acquired new importance for British authorities and the city’s growing bourgeoisie:

The upper middle class built new neighborhoods and even entire quarters in . . . Jerusalem’s southern neighborhoods of Talbiyya, Baq‘a, and Qatamon. The concentration of government offices in Jerusalem, the city’s large Christian population, and its proximity to other Christian centers in Bethlehem and Ramallah made the city a magnet for educated Christians and Muslims and home to the largest upper middle class population in the Mandate period. In the same time the Arab middle class neighborhoods in Jerusalem were also the favorite lodging place for British Army officers and Government officials, often renting apartments or houses with their families, as well as some Jewish well-to-do families, mainly of Middle European origin. The predominance of government officials in the ranks of the new bourgeoisie was evident mainly in Jerusalem.62

Alongside its physical growth, the New City experienced institutional and financial growth. Luxury hotels were built on the west side of the city, reflecting the level of commercial life. The King David Hotel was built in 1931, as well as the Palace Hotel, which was built by the Supreme Muslim Council in 1929, in part as the Arab counterpart to the Jewish King David.63 They were joined by the YMCA, which was described as the “handsomest Y.M.C.A. in the entire world,”64 and which provided Jerusalem with its first heated swimming pool and indoor basketball court. The YMCA building was designed by Q. L. Harmon, the same architect who designed the Empire State Building in New York. The YMCA went on to become a major society hub for the community in those decades before the Nakba. As Jacob Nammar recalls:

The Y was built as a monument to ecumenism. Its architectural décor, which embodies the symbols of the three monotheistic religions, was designed as an attempt to create better understanding, harmony, and tolerance among all of Palestine’s inhabitants. The Y was a multireligious center that included Christian, Muslim, and Jewish members, and that prided itself in working on interracial, interfaith, and peaceseeking activities, without distinction or creed, with all peoples.65

A Vibrant, Evolving Society

Literacy and education

Fueled by the growth and modernization of Jerusalem, at the turn of the 20th century, Palestinian society “underwent an accelerated transformation from widespread illiteracy to extensive dependence on the written word.”66 Bookshops, libraries, and public reading rooms sprang up all over the country. During the first half of the century, the leading Palestinian families in Jerusalem took pride in their private libraries, and

there was actually a competition between the wealthy Jerusalem families of having the largest and best library collection. And there was a tradition of . . . opening these libraries to the public. They played a role as public libraries . . . when municipal public libraries did not exist.67

We inhabited the first floor, above our neighbor the renowned Arab philologist Adel Jabr. I recall the long evenings he would spend with my father in the living room, discussing some issue of history, jurisprudence, or philology. My father might summon me to fetch them a book or another, and those would be my happiest moments, for I was entrusted with the library, and knew where to find each and every book. I cannot remember that my father ever said to me, “Don’t go near that shelf,” or “You’re not allowed to see this book.” To him, books and freedom were one and the same thing. I was aware that ours was not one of those wealthy households with opulent furnishings, and used to deride those who gave so much importance to appearances. I liked having books in every corner of the house, not just in my father’s room, which had seven identical bookcases. Every one of us had their own private book collection; even my younger sister Jinan had her own shelves crammed with children’s books.68

Alongside this blossoming literary appetite, there was a wealth of schools in the New City that offered instruction in a range of European languages. Many of these schools were run by Europeans, including in the German Colony. Hala Sakakini recalls her time in the German school she attended with her sister Dumia:

There were only a handful of Arab and English pupils among the hundred or so German children . . . Our school was conveniently close to the house; we could reach it on foot in about seven minutes. As most of our classmates and friends lived in the German Colony too, the whole Colony became our playground and we grew to love every part of it.69

Other important schools that were built in Jerusalem during the 19th and early 20th centuries by European missionaries include:

- St. George’s School (Madrasat al-Mutran) on Nablus Road, north of the Old City, established 1899 (primary teaching language: English)

- Bishop Gobat School (now the Jerusalem University College) on Mount Zion, east of the Old City, established 1847 (primary teaching language: English)

- Terra Sancta College, built in 1926 on the cusp between Talbiyya and Rehavia (primary teaching language: English)

- College de Frères, off the New Gate, established 1882 (primary teaching language: French)

- St. Joseph’s Convent and School, just northwest of the Old City (primary teaching language: French)

- Templar School in the German Colony (primary teaching language: German)

- Al-Dusturiyya (Constitution School), established in 1909 in Musrara by Khalil Sakakini

- Al-Wataniyya (The National School) in Upper Baq‘a, founded by Khalil Sakakini

- Men’s Teacher Training Centre on Zahra Street in East Jerusalem, which later became the famous Arab College, or al-Kulliyya al-‘Arabiyya

- Kulliyyat al-Nahda (The Revival or Renaissance School) in al-Baq‘a, founded by Khalil Sakakini in 1938 at the base of Jabal Mukabbir (primary teaching language: Arabic)

The plethora and diversity of schools established in Jerusalem indicated the importance of education to a thriving, cosmopolitan society. To that extent, it indicates the degree to which a vibrant and adaptive society was lost following 1948.

Terra Sancta College, located between Talbiyya and Rehavia, was built in 1926. It was erected on about 11 acres as part of the Franciscan Middle East Order. The college operated until the end of the British Mandate period and was considered one of the best high schools in the city. Classes were taught in English, and students were mostly Christian residents of Talbiyya, though Muslim and Jewish students also attended. Many graduates went on to hold prominent positions in government and in commerce during the Mandate period.70

The Arab College, the most prestigious Arab school in Palestine, was established in 1918 in the neighborhood by Bab al-Sahira (Herod’s Gate) in the Old City. Until 1934, when it was relocated to Jabal Mukabbir, southeast of the Old City, the college was run out of rented buildings in the Old City.71

Over the years, the school established such a reputation for itself that Arab students from across the country were handpicked to attend it. The prominent Ahmad Sameh al-Khalidi, father of Walid and Tarif al-Khalidi, was its principal between 1925 and 1948. It closed during the 1948 War, and its buildings were used as UN headquarters for a few years thereafter.

Thriving social and political life

Alongside prestigious schools, residents of Jerusalem’s New City enjoyed luxurious lifestyles. This included the wealthy Palestinian families who lived there, and the state officials and diplomats who lived in the vicinity of their embassies and consulates. These consulates held lavish events, inviting diplomats and city notables. Newspapers reported on these parties. For example, Filastin newspaper printed the following headline on June 14, 1942: “A Czechoslovak Consulate Party in Jerusalem on Celebrating the Visit of General Inger, Minister of Defense.”72

As another example, the Egyptian consulate used Filastin to announce its upcoming event in Jerusalem to congratulate King Farouk of Egypt upon ascending to the throne:

In celebration of His Majesty King Farouk the First, King of Egypt . . . the Egyptian Royal Consulate for Palestine and Transjordan will hold a reception on Thursday 29 July 1937, His Excellency the Consul will host the honorable congratulators as follows: from 11 to 12:30 in the afternoon the Honorable Heads of the authorities Officials [state officials], the consuls of the states, the spiritual leaders, and the non-Egyptian notables.

From five o’clock in the afternoon, distinguished members of the Egyptian community residing in Palestine and eastern Jordan, after which a tea party for the Egyptians will be held at the consulate.73

Some of the diplomats even rented out apartments of Arab landowners.

Jerusalem was also a place of refuge for European politicians who escaped wars in their countries. One of these politicians was former Yugoslavian king Peter, who was exiled from his country in 1941 with the occupation of Yugoslavia. The former king came to Palestine and lived for a few weeks in his country’s consulate apartment in the family home of the late Palestinian philosopher Edward Said.74

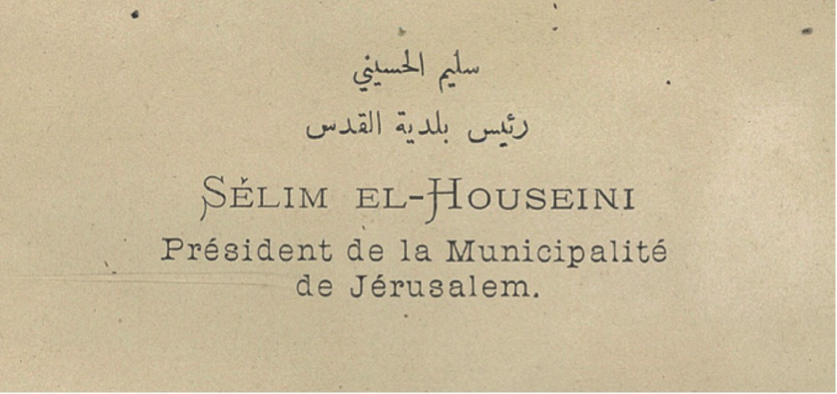

Business encounters

Middle- and upper-class residents of Jerusalem used to advertise themselves, their work, and their status using visiting cards. The movement of European migrants and investors in the city encouraged local and native business owners and professionals to represent themselves primarily in European languages, but also sometimes in Italian, German, Greek, Arabic, Turkish, Hebrew, Armenian, Russian, Spanish, Portuguese, and other languages, reflecting the identity of both the city’s residents and its visitors.75 Two or three languages combined on a small card was the norm. Visiting cards were also used by politicians.

The use and prevalence of such visiting cards suggests that Jerusalem in the 19th and 20th centuries was a vibrant and cosmopolitan city with a highly educated, entrepreneurial, and multilingual society.

A culture of photography

Photography, a growing form of gentrification across much of the world starting in the mid-19th century, spread to Jerusalem’s urban and cosmopolitan population. Photography was invented in 1839, and arrived in Palestine shortly thereafter. However, Palestinians did not take it up professionally until late in the century. Armenian photographer Garabed Krikorian was the first to open a studio in the city in 1885.76 New City residents flocked to his studio to pose for photographs which would later be displayed in their lavish homes as a sign of their affluence.

Photography flourished in Jerusalem in the late Ottoman and Mandate periods giving the city a wealth of choices. Especially along Jaffa Street in the New City, there were numerous establishments and also photography supply stores. These included the studios of Krikorian (who worked with David Sabunji of Jaffa), Khalil Raad (who first worked with Krikorian and then was the second to open a studio), Militad Savvides, Boulos Meo, Elia Studio, Jacob Ben Dov, and others, as well as the following photography stores: Photo Prisma, Photo Europa, Ganan, and Abraham Yehezkeli.77

Photography was not limited to the studio, either. In his memoir, Edward Said recalls that:

Khalil Raad’s hooded tripod camera [was] always summoned by my aunt and her sons to an important occasion. A slightly built white-haired man, Raad took a great deal of time as he arranged the large group of family and guests into acceptable order . . . No one then knew that Raad’s photos would become perhaps the richest archival resource for Palestinians lives until 1948.78

There was also the work done by photographers at the American Colony Photo Department, which began informally with the arrival of the Christian pilgrims who immigrated in 1881 and founded the colony, and then more formally in 1898 with the visit of Kaiser Wilhelm II to Jerusalem. This work continued over several decades until 1934, when the colony disbanded.

One of its photographers, Eric Matson, gained control of the photo department and all its files and equipment. Renaming themselves the “Matson Photo Service” in 1940, Matson and his American wife continued the work until 1946, when, given the rising violence, they left Jerusalem for California. Their team also included two Palestinian photographers, Hanna Safieh (who apprenticed with Matson) and Joseph Giries.79

According to Ariella Azoulay, professor of modern media and culture at Brown University:

This is one of the major sites where much of the history of early photographic activity in Palestine took place: an urban open-ended space where many photographers had their studios, and persons came by to have their photos taken or to buy those of others, and distant spectators acted and interacted according to variegated protocols that they shaped and adopted. In a dense, fruitful, and challenging urban fabric, frequented by at least 1,000 people each day, male and female professionals labored together as operators of cameras, assistants, those preoccupied with lighting, those who developed the negatives and those who printed them, those who retouched photographs, and others who designed the space with accessories to accommodate different photographed persons’ taste and helped them find the right dress. Those spaces were frequented by collectors and travelers, tourists and local clients, photographed persons of all kinds who came to buy photographs and postcards of themselves and of others, of beloved or exotic places and varied landscapes. This street and the entire neighborhood were the beating heart of the photographic field of Palestine. A ten-minute walk away from there were the studios of Rassas, Za’rur, and Hana Safieh, as well as the American Colony studio.

The activity of these photographers combined studio work and a fascinating documentation project of Palestine as it was undergoing political, cultural, and social development. With time, the drawers and shelves of each of these studios contained a rich archive of photographs of life in Palestine and a unique record of a vivid local photographic culture.80

Azoulay goes on to remark that the photography scene was not segregated or divided along any lines:

From our perspective today, it is tempting to say that a mixture of ethnic and national groups had been formed by means of photographic activity. However, a more accurate historical description would be that, in this area of Jerusalem, photographers, photographed persons, and spectators mingled without conceiving of themselves in total opposition to others. The binary division of the world into Arabs and Jews was not operative and certainly not absolute, and photographers, for example, were known by their names, advertised on the street signs, and their geographical provenance: Armenian, Safadi, or Jerusalemite. The camera enabled them to be attracted by or remain oblivious to ethnic and national origins—certainly not to recognize in them a commanding law. These forms of identification did not limit or subsume their actions and interactions with others—whether with the photographed persons caught in the lens, the clients who patronized the shops, or, certainly, those with whom they shared a passion for photography.81

Safieh continued to work in Jerusalem after the Matsons left. In his new position as a British government public information officer, he had ample opportunity to train his camera everywhere. His unique body of work focused on life and events in the city, as opposed to the studio portraiture style that was popular at the time. Most notably, he went to the village of Deir Yasin the day after the massacre that took place there on April 9, 1948, and documented the gruesome aftermath before it could be cleared. In sum, his work created an invaluable historical record of Palestine in those decades.

This dynamic and vibrant cosmopolitan community life that was organically developing in the New City was not fated to endure. Following four brutal years of oppression, economic devastation, and starvation under the Ottomans during World War I (1914–18), Britain militarily occupied Palestine for three years until it established its mandate. What followed would permanently transform Palestine to the present day.

The End of Ottoman Rule in Palestine

The Ottoman Empire’s 400-year rule in Palestine—and the Middle East, for that matter—came to an abrupt end when British forces marched through the Old City in December 1917, effectively removing Turkish presence from Palestine. Britain’s subsequent occupation of Palestine lasted for 30 years.

Jerusalem’s status as a thriving, cosmopolitan, and diverse city would gradually change with the entrenchment of British rule in Palestine. Beyond military, administrative, legal, economic, and infrastructural changes, the British introduced radical changes to the city’s demographic character. With their 1917 promise to the Zionists to establish a “national home” for the Jews in Palestine, and with their headquarters based in Jerusalem, British authorities laid the groundwork for a segregated and tense city.

What was once home to a population of multi-confessional, multinational, and multiethnic residents turned into an increasingly divided landscape of Jewish-only neighborhoods, institutions, and security forces. For 30 years during Britain’s mandate over Palestine, non-Jewish Palestinian Arabs in Jerusalem continually responded with anti-colonial nationalist activism, including through protests and demonstrations, but also through uprising and rebellion. With the ouster of the Ottomans, therefore, Jerusalem and its inhabitants would never be the same again.

Part 2 takes a closer look at the New City's evolution and subsequent unravelling under the British Mandate, and especially in the aftermath of its untimely end.

Contributors

Kate Rouhana and Nadim Bawalsa of the Jerusalem Story Team collaborated on the research, writing, and editing for this Backgrounder.

Shahrazad Odeh, formerly with Jerusalem Story, worked on an early version of this Backgrounder.

Notes

Salim Tamari, “The Phantom City,” in The Arab Neighbourhoods and Their Fate in the War, 2nd ed., ed. Salim Tamari (Jerusalem and Bethlehem: Institute for Jerusalem Studies and Badil Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights), 1.

Rochelle Davis, “Growing Up Palestinian in Jerusalem before 1948: Childhood Memories of Communal Life, Education, and Political Awareness,” in Jerusalem Interrupted: Modernity and Colonial Transformation, ed. Lena Jayyusi (Northampton: Olive Tress Press, 2015), 187–210.

Thomas Ricks, “Jerusalem: City of Dreams, City of Sorrow,” The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad 20, no. 1 (2011): 1–16.

While a UN-declared ceasefire took effect on January 7, 1949, the armistice agreements were hammered out between Israel and its Arab neighbors over a period of months, from February and July 1949. The agreement with Egypt was signed on February 24, 1949; with Lebanon, on March 23, 1949; with Jordan, on April 3, 1949; and with Syria on July 20, 1949.

Jacob Nammar, Born in Jerusalem, Born Palestinian: A Memoir (Northampton: Olive Branch Press, 2012), 6.

Rochelle Davis, “Ottoman Jerusalem: The Growth of the City outside the Walls,” in Jerusalem 1948, 11.

Davis, “Ottoman Jerusalem,” 11.

Davis, “Ottoman Jerusalem,” 20–21.

Davis, “Ottoman Jerusalem,” 22–23, citing David Yellin, Writings, I (1899–90), 386–88.

Halah Ahmad, “Tourism in Service of Occupation and Annexation,” al-Shabaka, October 13, 2020.

According to the Jewish Virtual Library, “The Yishuv was a national liberation movement aspiring to establish an independent Jewish entity in Palestine, though, unlike other such movements, it had to gather its constituency from all over the world . . . The term Yishuv, which is usually defined as ‘the Jewish community in pre-State Palestine,’ actually relates only to those Jews who aspired to the national revival of the Jewish people in Palestine or Eretz Yisrael, the Land of Israel. The Yishuv was made up of those who were involved in the political life of the Jewish community through elections, who accepted the authority of the elected leadership and who took part in the cultural life, based on the Hebrew language. From the early 1920s, two groups of Jews excluded themselves from the Yishuv: the ultra-orthodox and the communists.” Aviva Halamish, “Israel Studies an Anthology: The Yishuv: The Jewish Community in Mandatory Palestine,” Jewish Virtual Library, September 2009.

Jehuda Reinharz, “Old and New Yishuv: The Jewish Community in Palestine at the Turn of the Twentieth Century,” Jewish Studies Quarterly 1, no. 1 (1993/94): 54–71.

“Large Areas Owned by the Jews: Within the Realm of Khansikin, Tayba, and Naora” [in Arabic], Filastin, September 25, 1934 (retrieved from the National Library of Israel). All contemporaneous newspaper accounts from the Arabic press at the time are translations rendered by coauthor Shahrazad Odeh, a former Jerusalem Story researcher.

Halamish, “Israel Studies.”

Wadi‘ ‘Awawada, “The Houses of West Jerusalem Testify to Their Identity” [in Arabic], Al Jazeera, March 30, 2016.

Danna Piroyansky, “From Island to Archipelago: The Sakakini House in Qatamon and Its Shifting Ownerships throughout the Twentieth Century,” Middle Eastern Studies 46, no. 6 (2012): 857.

Ghada Karmi, “Leaving the Lemon Tree,” The Tablet, April 25, 1998.

Nammar, Born in Jerusalem, 6.

Taher al-Nammari, “The Namamreh Neighborhood in Baq’a,” in Jerusalem 1948, 294–97.

The ashraf (أشراف) claim descent from the Prophet Muhammad by way of his daughter Fatima. See “Information on the Ashraf Clan,” Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, November 23, 2010.

David Kroyanker, Jerusalem Neighborhoods: Talbiyeh, Qatamon, and the Greek Colony (Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, 2002), 159.

Kroyanker, Jerusalem Neighborhoods, 179.

Piroyansky, “From Island to Archipelago,” 857.

Edward Said, Out of Place (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 2000), 110.

Nammar, Born in Jerusalem, 6.

‘Awawada, “The Houses of West Jerusalem.”

Piroyansky, “From Island to Archipelago,” 859–60.

Dalia Carpel, “Villa Dolorosa: The Story of Vila Salameh,” Haaretz, January 8, 2003.

Kroyanker, Jerusalem Neighborhoods, 66.

Carpel, “Villa Dolorosa.”

Jamil Toubbeh, Day of the Long Night: A Palestinian Refugee Remembers the Nakba (Jefferson, NC: McFarland Publishing, 1997), 21.

Hala Sakakini, “Jerusalem and I: A Personal Record,” Islamic Studies 40, nos. 3–4 (2001): 483–85.

Nammar, Born in Jerusalem, 26.

Said, Out of Place, 20–21.

Piroyansky, “From Island to Archipelago,” 860.

Raffi Berg, “The Templars: German Settlers Who Left Their Mark on Palestine,” BBC News, July 12, 2013.

Itamar Katz and Ruth Kark, “The Church and Landed Property: The Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem,” Middle Eastern Studies 43, no. 3 (May 2007): 383–408. According to Katz and Kark (383), these land purchases were so extensive that even today, the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem is one of the largest nongovernmental landowners in Israel.

Katz and Kark, “The Church and Landed Property.”

Piroyansky, “From Island to Archipelago,” 860.

Salim Tamari, “The City and Its Rural Hinterland,” in Jerusalem 1948, 77. Extensive details of these villages are compiled in Walid Khalidi, ed., All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948 (Washington, DC: Institute of Palestine Studies, 1992).

Rana Barakat, “The Jerusalem Fellah: Popular Politics in Mandate-Era Palestine,” Journal of Palestine Studies 48, no. 1 (2016): 9.

Ghada Karmi, In Search of Fatima (London: Verso, 2002), 15–18.

Barakat, “The Jerusalem Fellah,” 9.

Karmi, In Search of Fatima, 15–18.

A. Vale, “The Jaffa-Jerusalem Railway,” The Railway Magazine (1902): 329.

Selah Merrill, “The Jaffa-Jerusalem Railway,” Scribner’s Magazine 13, no. 3 (1893): 289–300.

Merill, “The Jaffa-Jerusalem Railway,” 300.

Khalid ‘Awdat Allah, “Jaffa, Jerusalem: A Brief History of Colonialism” [in Arabic], Bab al-Wad, October 17, 2018.

‘Awdat Allah, “Jaffa.”

‘Awdat Allah, “Jaffa.”

Vale, “The Jaffa-Jerusalem Railway,” 327.

‘Awdat Allah, “Jaffa.”

Maria Chiara Rioli, “Introducing Jerusalem: Visiting Cards, Advertisements and Urban Identities at the Turn of the Twentieth Century,” in Ordinary Jerusalem, 1840–1940: Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City, ed. Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire (Leiden: Brill, 2018, 29–49.

‘Awdat Allah, “Jaffa.”

“Jerusalem’s First Train Station,” Central Zionist Archives.

Vincent Lemire, Jerusalem 1900: The Holy City in the Age of Possibilities (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 129.

Lemire, Jerusalem 1900, 130.

Lemire, Jerusalem 1900, 131.

Ruth Kark, “The Contribution of the Ottoman Regime to the Development of Jerusalem and Jaffa, 1840–1917,” in Palestine in the Late Ottoman Period, ed. David Kushnir (Leiden: Brill, 1986), 53.

David Eisenstadt, “Jerusalem: Life throughout the Ages in a Holy City,” Ingeborg Rennert Center for Jerusalem Studies, May 1997.

Kark, “Contribution,” 53.

Itamar Radai, “The Rise and Fall of the Palestinian Middle Class under the British Mandate, 1920–39,” Journal of Contemporary History 51, no. 3 (2016): 487–506.

Eisenstadt, “Jerusalem.”

Nadi Abousaada, "The Palace Hotel in Jerusalem: History beyond Memory," Institute for Palestine Studies blog, May 4, 2020. The author notes that the hotel went on to play important roles, both in the Palestinian national movement and in the British Mandate, as it was the site of the offices of the 1936 Peel Commission and hence the site where Partition Plan was deliberated.

Nammar, Born in Jerusalem, 93.

Gish Amit, “Salvage or Plunder? Israel’s ‘Collection’ of Private Palestinian Libraries in West Jerusalem,” Journal of Palestine Studies 40, no. 4 (2011): 6.

Erling Bergan, “Libraries in the West Bank and Gaza: Obstacles and possibilities,” IFLA, August 13–18, 2000.

Bayan Nuwayhed al-Hout, “Evenings in Upper Baq’a: Remembering Ajaj Nuwayed and Home,” Jerusalem Quarterly 46 (2011): 20.

Hala Sakakini, Jerusalem and I: A Personal Record (Amman: Economic Press Company, 1990), 16.

Kroyanker, Jerusalem Neighborhoods, 158.

Sadiq Ibrahim ‘Odeh, “The Arab College in Jerusalem, 1918–1948: Recollections,” Jerusalem Quarterly 9 (2000): 48–58.

A Czechoslovak Consulate Party in Jerusalem on Celebrating the Visit of General Inger, Minister of Defense” [in Arabic], Filastin, June 14, 1942 (retrieved from the National Library of Israel).

“The Egyptian Consulate in Jerusalem Celebrates His Majesty King Farouk Assuming the Reins of the King” [in Arabic], Filastin, July 24, 1937 (retrieved from the National Library of Israel).

Kroyanker, Jerusalem Neighborhoods, 169.

Rioli, “Introducing Jerusalem.”

Issam Nasser, “A Jerusalem Photographer: The Life and Work of Hanna Safieh,” Jerusalem Quarterly 7 (2000): 24–28.

Ariella Azoulay, “The Imperial Condition of Photography in Palestine,” Graylit, November 1, 2019.

Said, Out of Place, 76–77.

For more about the work of Hanna Safieh, see Nasser, “A Jerusalem Photographer”; Hanna Safieh, A Man and His Camera: Photographs of Palestine, 1927–1967 (Jerusalem: Hanna Safieh, 1999).

Azoulay, “The Imperial Condition.”

Azoulay, “The Imperial Condition.”