Recently, media coverage has been extensive about Zionist attempts to uproot Palestinian residents from a targeted section of the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood in Jerusalem, to make way for its colonization by settlers. There are multiple reasons why local and international media have focused on the Sheikh Jarrah colonization efforts. What is happening—the uprooting and displacement of Palestinian refugees for the second time—is related directly to refugees’ right of return. The plethora of foreign institutions and consulates based in Sheikh Jarrah meant that the issue of the neighborhood garnered special international concern. The social and cultural environment of the neighborhood is likely a major reason behind the ability of residents to be heard when they raise their voices and organize protests to appeal to the media. We bring up the issue of Sheikh Jarrah, which we have dealt with before extensively,1 as a complementing and contrasting counterpoint to the situation that another Jerusalem neighborhood—Silwan—has been living through for decades.

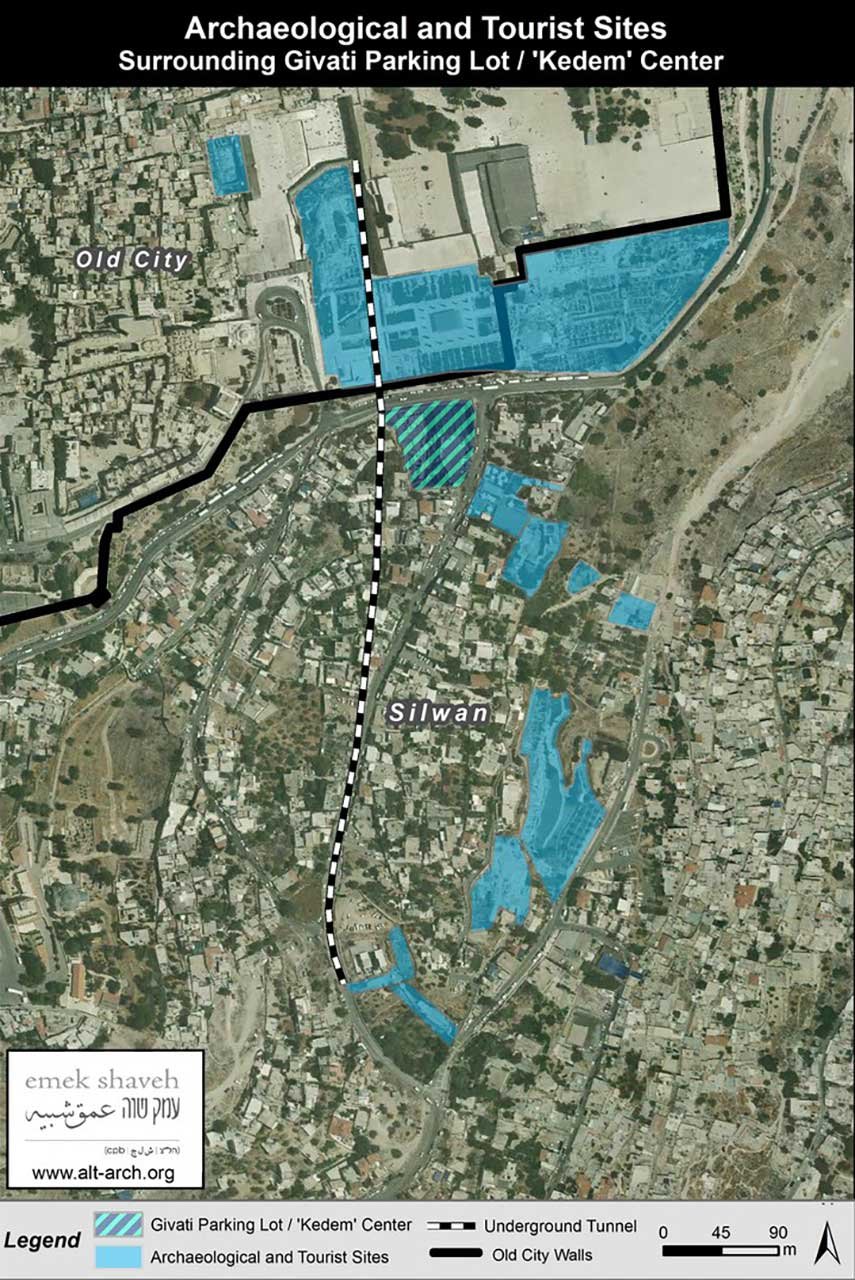

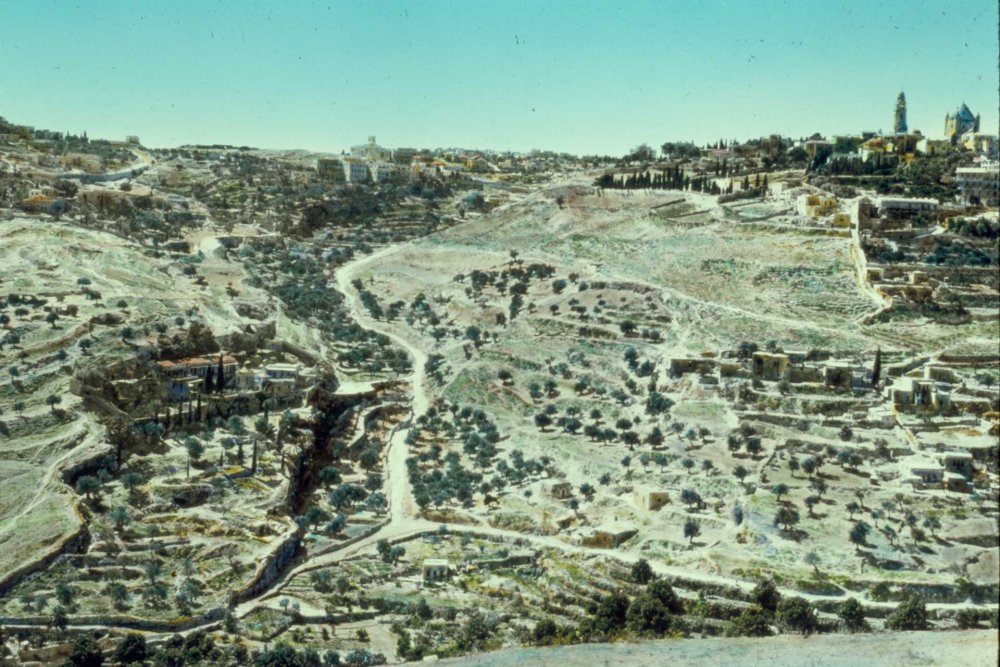

It is not possible to understand what is happening in Silwan in isolation from the overall battle for survival being waged ceaselessly throughout Old Jerusalem, inside and outside its walls. Certainly, it is also broadly related to the survival of the city’s identity and culture, and the outcome will determine its future. Silwan’s situation encapsulates all control of space strategies and tools used to manipulate the population and influence demographics. It clearly demonstrates the battle of existence by the indigenous population against the armed occupation forces who use a seemingly limitless array of tools that were conjured before and after the Israeli occupation in 1967 to achieve their settler-colonial goals.

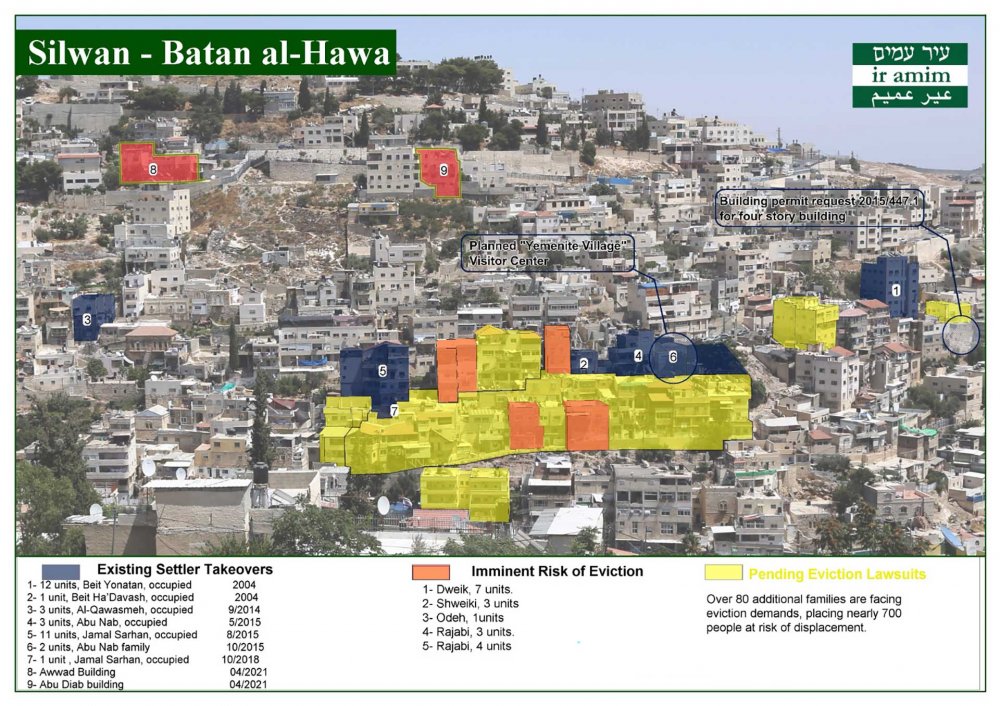

This article will attempt to draw a general picture of Silwan, with its various subdivisions, and focus on the motives and mechanisms of settler colonialism therein, and its impact on Silwan, and on Jerusalem in general.