The US government is considering building its embassy in Jerusalem on Palestinian land that Israel seized after the state was established.

The State Department is continuing implementation of former president Donald Trump’s controversial decision to move the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, seeking to build the diplomatic site on land that formerly held the Allenby Barracks on Hebron Road in West Jerusalem. The plot includes private Palestinian and waqf land illegally confiscated by Israel using the 1950 Absentees’ Property Law, the main legal instrument Israel has used to confiscate land and other property belonging to displaced Palestinians. Israel applied this law retroactively to certain individuals who left their property as of November 29, 1947 (see How Israel Applies the Absentees’ Property Law to Confiscate Palestinian Property), classifying them as “absentees” and seizing their property.

The US has been leasing the property from the State of Israel since January 18, 1989, for $1 each year, renewable for 99 years and covering 31,250 square meters (7.7 acres).1

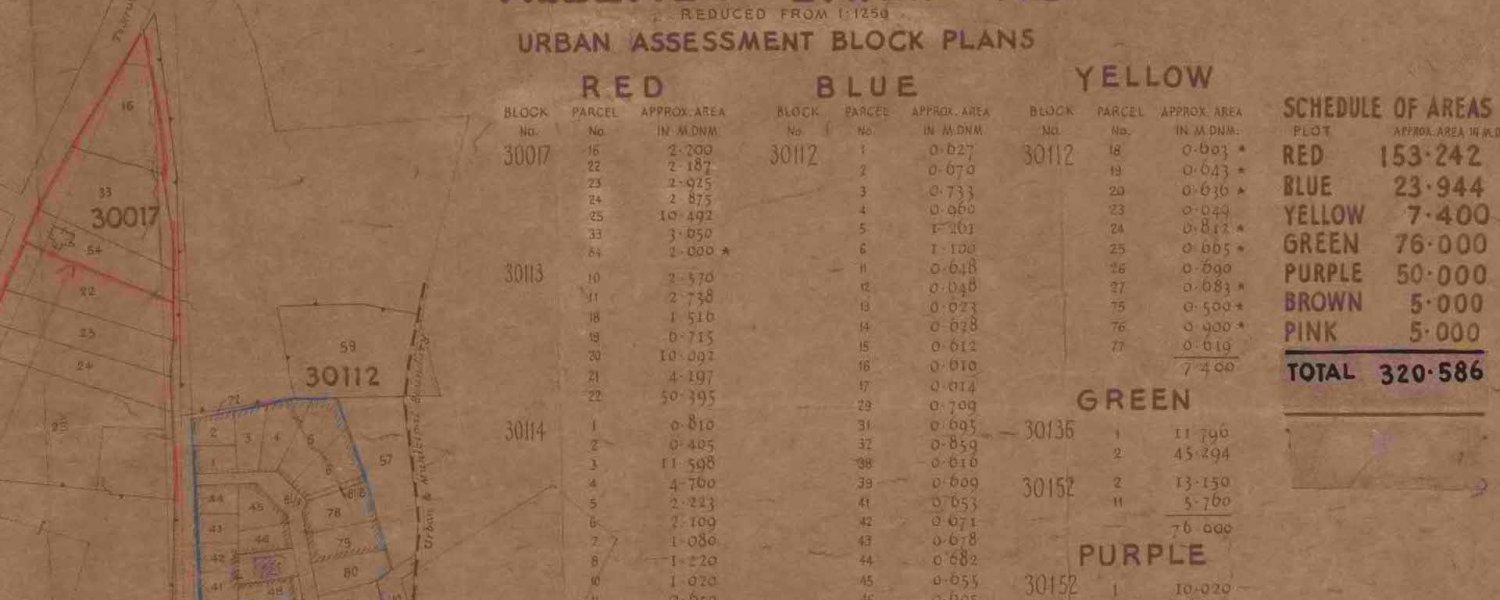

This month, the subcommittee for objections of the Jerusalem District Planning Committee convened to discuss multiple objections to the proposed plan—including one submitted in January by Adalah—The Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel. Adalah found, and subsequently published in July 2022, Israeli state archival records proving the land belongs to several Palestinian families. The documents are the official lease agreements between the Palestinian landowners and British Mandate authorities, who rented the property from the landowners before Israel was established in 1948.

The aggrieved landowners in the embassy case include members of the Khalidi, al-Fitiani, El Khalili, Abu Soud, and Qleibo families, among others.

Adalah filed its objection on behalf of 12 of the landowners’ descendants. These include four US citizens, three Jordanian residents, and five residents of occupied East Jerusalem.2