Overview

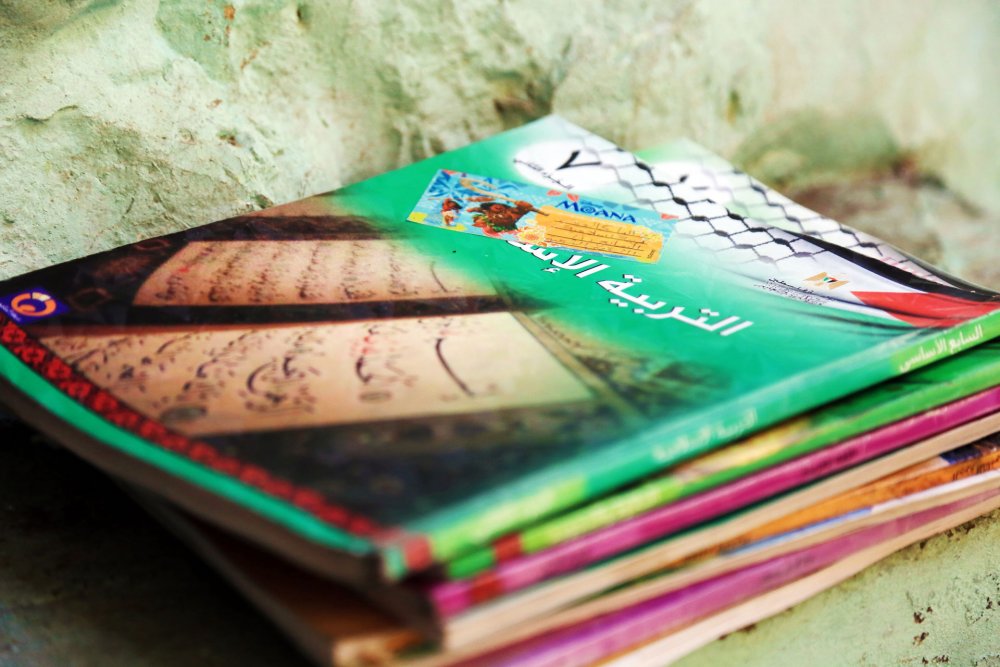

Credit:

Saeed Qaq, APA Images

Ir Amim Issues New Report on Education in East Jerusalem, Tracking Severe Challenges Facing Schools There

Snapshot

A new report finds a modicum of progress in a dire situation that mostly remains stalled.

Just as the new school year kicked off in East Jerusalem in September, Ir Amim, an Israeli nonprofit monitoring Jerusalem, released its report on the state of education over the last year.1 Based on a Freedom of Information request Ir Amim sent to the Jerusalem Municipality, the report (in Hebrew) examines the major challenges facing East Jerusalem’s schools. These include a severe shortage of classrooms, the Israeli government’s attempts to pressure Palestinian schools to switch to the Israeli curriculum, and identifying where tens of thousands of “invisible” Palestinian children in East Jerusalem attend school.

According to the report, East Jerusalem has a shortage of 2,447 classrooms.2 This is despite a January 2023 Israeli Supreme Court ruling ordering the state to submit a plan for building more classrooms. According to Ir Amim’s findings, the municipality has only begun planning for 1,210 classrooms, which is less than half of the number of classrooms needed to fill the gap.3

On the other hand, the municipality has begun locating where thousands of school-age children living in East Jerusalem study. The municipality knows a little over 20 percent of Palestinian students are not studying in official or recognized academic settings, meaning they study privately, under the Ministry of Labor, or have dropped out. Moreover, the municipality admits it doesn’t know where 11,000 East Jerusalem children are studying.4

Jerusalem Story spoke with Oshrat Maimon, policy advocacy director at Ir Amim, about the organization’s latest report on the status of education in East Jerusalem in 2023–24.

Jerusalem Story (JS): What are the report’s main findings regarding education in East Jerusalem in 2023–24?

Oshrat Maimon (OM): As always, there is still a shortage in the number of classrooms. We see a big success in our efforts [to investigate the situation of] the missing students for whom the municipality didn’t take any responsibility. Now, they’ve started to take some responsibility.

Maybe it’s not in the report itself, but I can say during the year of the war [since October 7, 2023], there were a lot of discussions in the Knesset [Israeli parliament] committees about more pressure on the curriculum. But there was no discussion—even in the first month—on the emotional crisis during the war and all the security that children faced on their way to the schools.

Even today, the head of the education committee’s subcommittee [on curricula in East Jerusalem], Avichai Boaron, is a very extreme Knesset member. He organized a tour for the subcommittee [of several East Jerusalem schools].5 I’m sure it’s trying to intimidate and bring more pressure. They say they’re looking for terrorists, but I think it’s more about exerting pressure on the curriculum. This isn’t in the report, but it’s one of specific things that happened during the war.

JS: The report highlights the issue of injecting the Israeli curriculum into East Jerusalem schools. So, as a new school year begins, what is the status of this issue?

OM: You can see it in the budget, because of government decision number 80, they allocated, again, more budget to transfer schools to the Israeli curriculum [from the Palestinian one]. So, of course, the pressure continues.

The pressure is exerted through two channels: one through the budget and the second one is through Knesset discussions. It’s a political issue, and it will continue to be political. And I don’t think that Israel will succeed [to fully Israelize the curriculum of Palestinian schools in East Jerusalem], because it’s really a part of the identity of the Palestinians.

It’s been six years already since the first government decision [for developing East Jerusalem], Decision 3790, yet from the Israeli government’s calculation, they are talking about 15 percent [of schools currently using the Israeli curriculum].6

JS: You say that you don’t think pressuring Palestinian schools to adopt the Israeli curriculum will be successful, but if they don’t, won’t they be stripped of funding or have their funding reduced?

OM: I don’t think you can call it reduction, but when you have money and you divide it unequally, then it creates a gap. For instance, the schools that use the Israeli curriculum get a lot more of the budget. So, the side effect is that there will be fewer students in schools [that don’t].

JS: How can we compare the situation of education in East Jerusalem in 2024 to last year?

OM: Every year we talk about the classroom shortage. Years ago, the municipality denied there was a shortage. And then they started to say, there is a shortage, but we have a plan. And then every year they say, “We built so much,” but still the number stays the same. It shows that nothing is really done.

The report talks about the Supreme Court verdict in January 2023, saying the state and the municipality have to submit a plan [on building classrooms] in four months, and since then, every few months, the state submits another request to prolong this date. And now the last date is December of this year [2024]. So here we are two years out from the Supreme Court decision, and we are still waiting for the plan that they always say that they have.

JS: The report addresses the issue of what’s been described as “missing children.” Could you discuss what that means and why this is such a significant issue in the larger context of education in East Jerusalem?

OM: Every person has a right to education. [According to Israeli law,] from age three, a child must have a place in the academic system. And also, this obliges the state to follow every child and to see that they are going to school.

For years, we knew that there are thousands of [Palestinian] children who are not in the numbers of the municipality and the Ministry of Education, so then we called them “the missing children.”7

For the first time this year, the government says they started to collect the names [of these children]. They are taking responsibility for this issue. Still, it’s not all of the names, but a part. And this is a success, that the government has started to understand their responsibility.

JS: What obstacles can we expect to see this school year?

OM: The first issue is the war and the solution to all the disputes in this region and in Jerusalem. The education system is a symbol of all of these disputes. And the war affects a lot of children emotionally.

Until there is a solution, we’ll continue to see a struggle. Because even the shortage of the classrooms—it’s not like nobody’s building because they don’t have money. It’s also a demographic issue and [more classrooms would mean] allocating more land to the Palestinians in East Jerusalem. It’s a big issue of discrimination and annexation.

And then there’s the status of East Jerusalem in the eyes of Israel and in the eyes of the International Court of Justice. It goes hand in hand with what happens there and whether we will have a new, less extreme right-wing government. It is all connected.

Notes

Ir Amim, East Jerusalem Education Report 2023–2024 [in Hebrew], August 2024.

Ir Amim, Education Report, 6.

Ir Amim, Education Report, 8.

Ir Amim, Education Report, 6.

Bentzi Rubin, “MKs to Tour East Jerusalem Schools, Push Palestinian to Israeli Curriculum Shift,” Jerusalem Post, September 23, 2024.

Rubin, “MKs.”

Ir Amim, The State of Education in East Jerusalem 2021–2022 (Jerusalem: September, 2022), 7.