Born in Jerusalem in 1936, Samia Halaby was from a young age captivated by the shapes and vibrant colors that made up her world. Her grandmother told her stories of Jerusalem and its people, and in her backyard garden young Halaby encountered the vivid images that would form the foundation of her future artwork.1

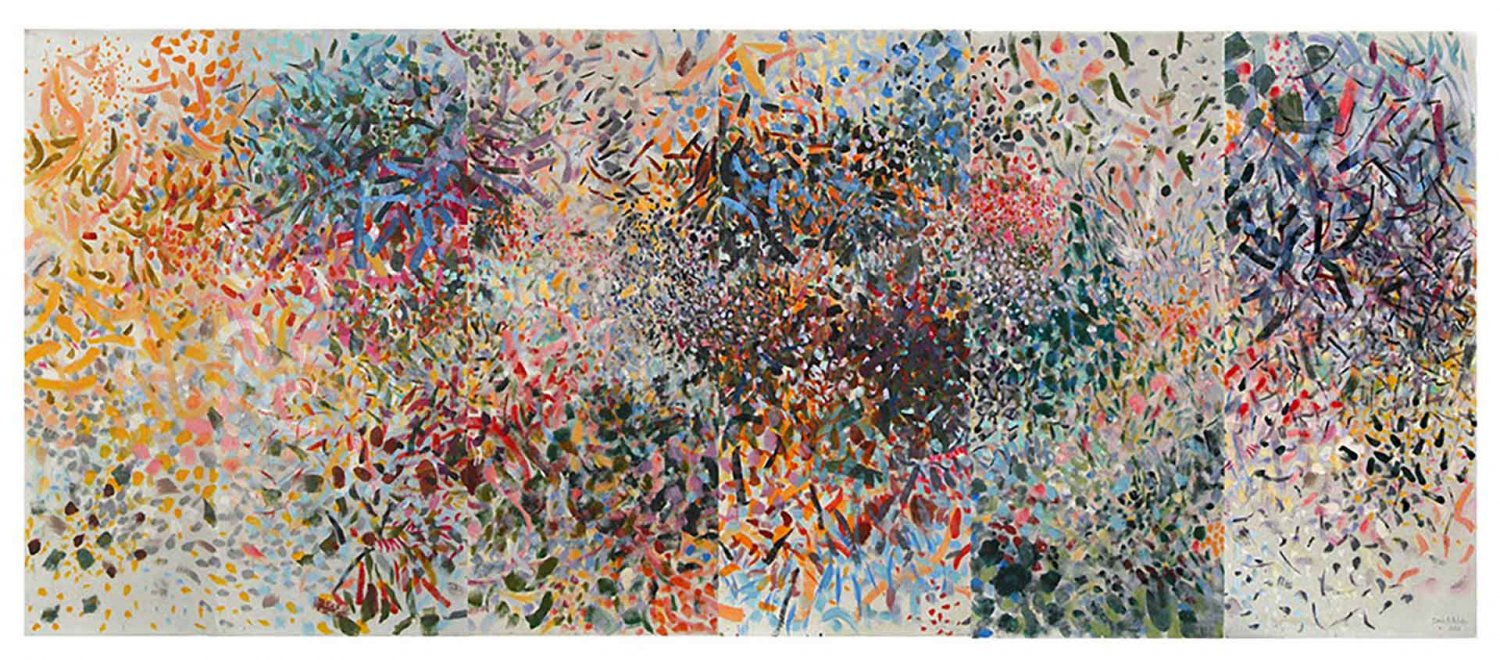

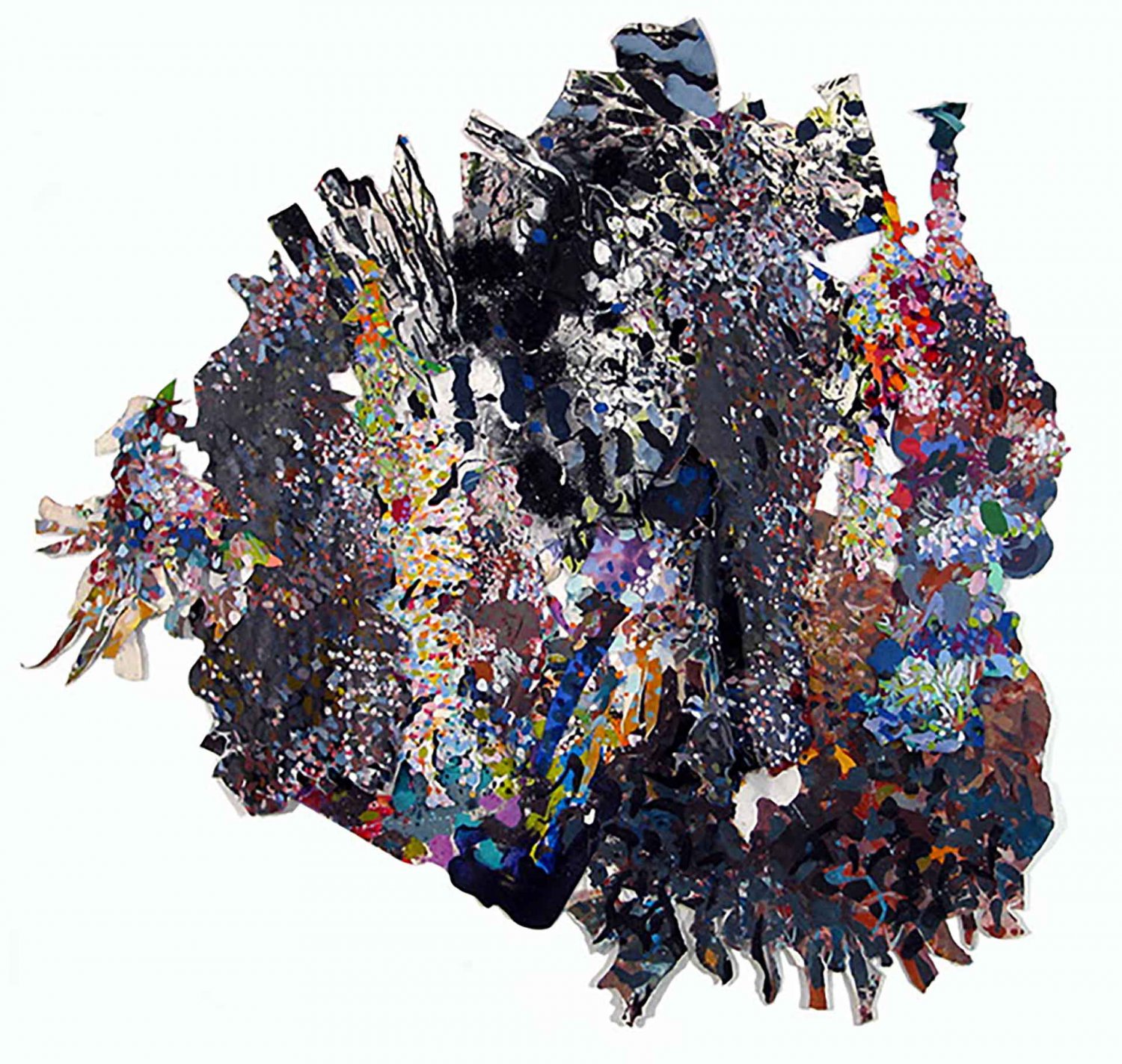

Halaby is a leading figure of abstract art practice and stands among the most influential Palestinian artists today (see Samia Halaby). Although based in the United States since 1951, Halaby is a pioneer of art in the Arab world.

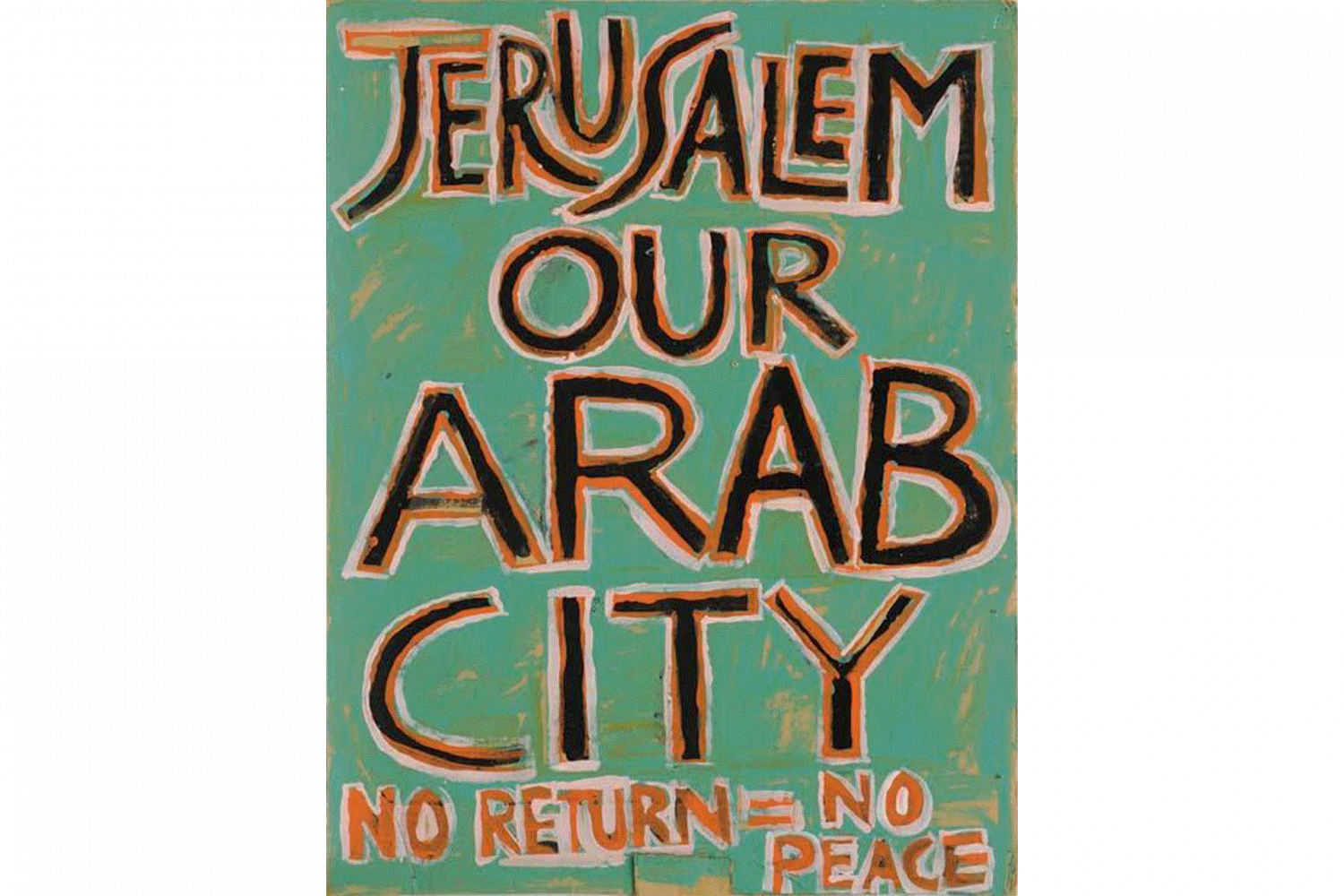

To date, Halaby has created more than 3,000 works of art in different mediums, depicting subjects from natural landscapes and urban scenery to abstract geometric paintings and political messages.

Halaby is mostly known for her abstract painting, the purpose of which was to imitate reality and represent emotion. Some illustrations featured her childhood home and were inspired by her personal experience. In 1966, while taking a break from painting, Halaby traveled to Jerusalem, Damascus, and Istanbul. These trips and subsequent ones to Jerusalem had a profound effect on her, inspiring several art series dedicated to the city. In those images, Halaby depicted iconic scenes from Jerusalem’s landscape and history using symmetrical diagonal lines, figural representation, and geometric shapes. These illustrations invoked the lived experience and enduring memory of Palestine and, at its heart, Jerusalem.

Halaby divides her own artistic oeuvre into three parts, saying “political posters and banners done mostly when I was an activist, documentary work on the Kafr Qasem massacre and the Israeli massacre of our olive trees, and third—my central artistic effort—explorative abstraction.”2 Samples of each of these types are presented in this Photo Album.

Her political artwork surrounding Jerusalem and Palestine, in the form of posters and sketches, was inspired by personal loss, tragedy, hope, and joy, which make them especially potent. The historical events, political messages, and contested places Halaby depicts in her work are part of Palestinian living memory.

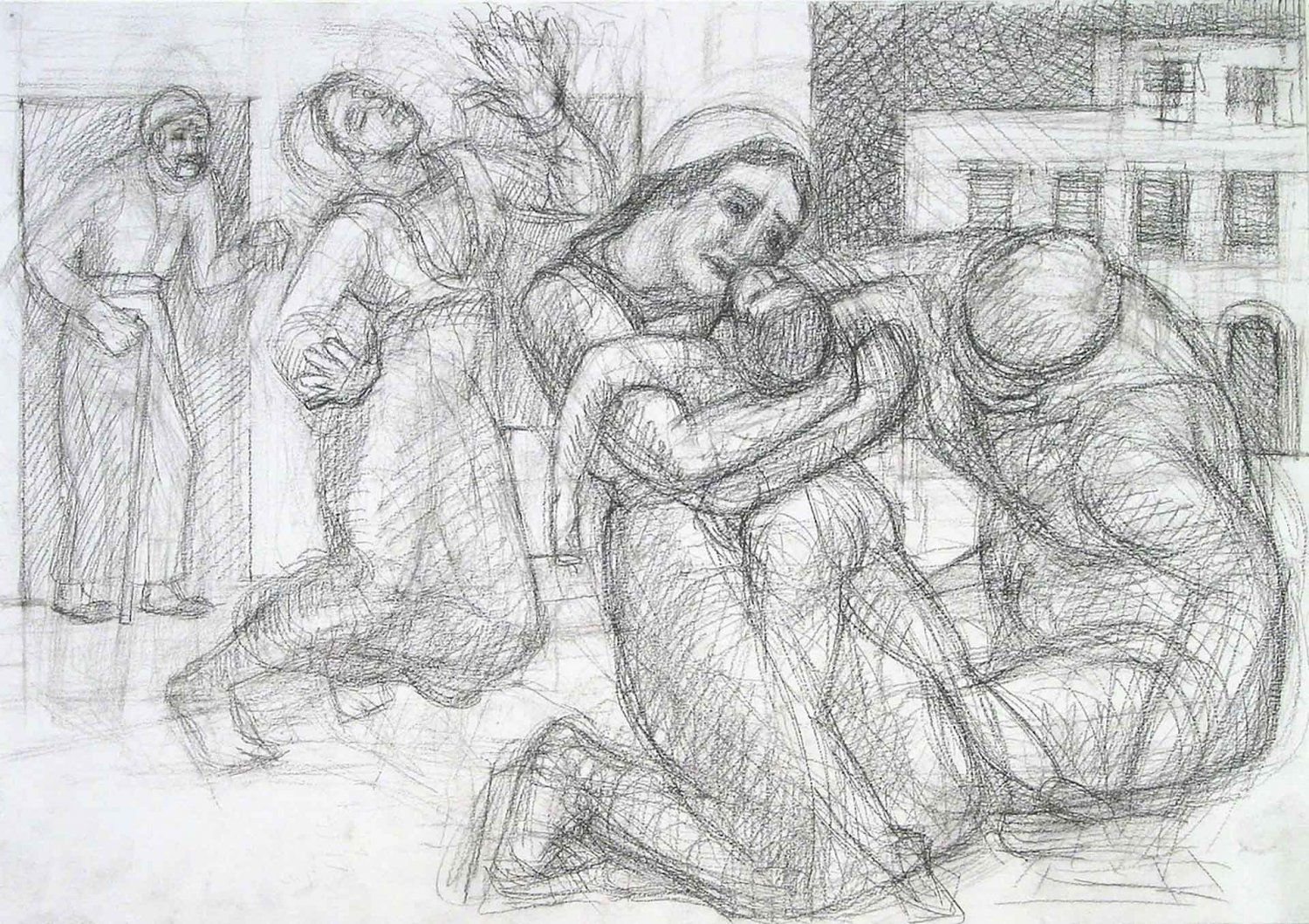

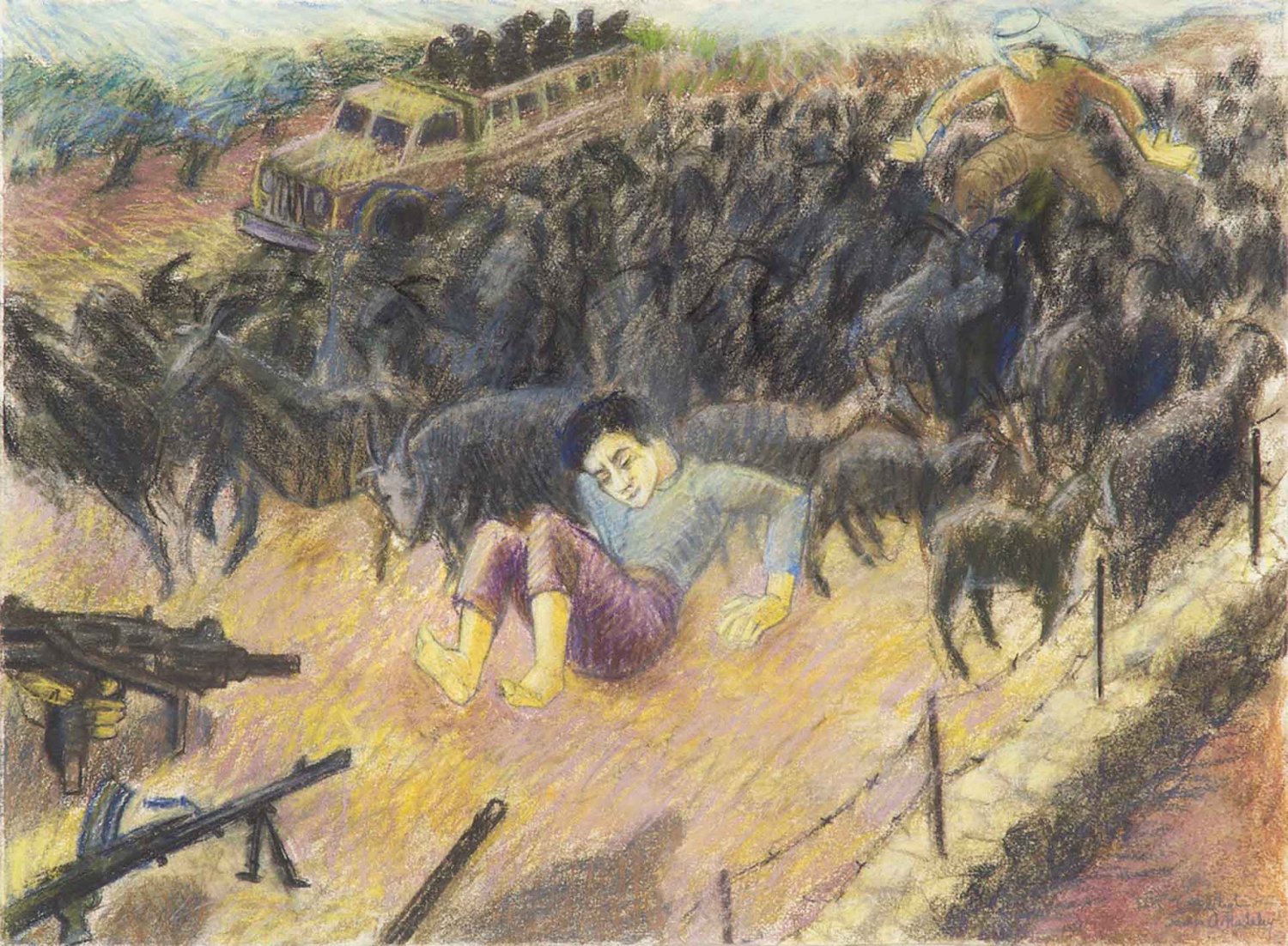

One of her more popular series consists of sketches of the Kufr Qasim massacre. The series consists of a sequence of images capturing, as photos would, scenes from a historical event, the massacre of Kufr Qasim. On October 29, 1956, Israel announced at 4:30 p.m. that the village would be placed under a curfew, to begin at 5:00 p.m. Inhabitants who were out of the village were unaware of the curfew, and at 4:55 p.m., Israeli soldiers began shooting men, women, and children on the streets. By the end of the day, 49 civilians had been massacred.

Halaby based this series on extensive research of “stories told by survivors, accounts they told of the families they had lost in the massacre, and all the press materials she could find.”3 The series was launched in an exhibition at the Bridge Gallery in New York on October 29, 1956, 50 years after the massacre. A decade later, in 2016, Halaby published a book, Drawing the Kafr Qasem Massacre, about the process of researching and documenting the massacre for the work.

In an article for Jadaliyya, Halaby shared: “When I first accepted the challenge of drawing the Kafr Qasem massacre, I wanted to represent its events as though I were a camera on site. Documentary drawings, I thought, could recreate what photography might have given us if done on a historical basis. I would learn all I could and present the specific individuals and the documented events. I worked on the project in three major periods, each occupying most of a year or several years. I began work in 1999 and continued into 2000. In 2006, on the occasion of the fiftieth memorial of the massacre, I created both a web page and an exhibition of the drawings. In 2012, I returned to the project with the intention of finalizing it by making large-scale drawings and developing a book.”4

Halaby decided to document this massacre to show the enduring strength and bravery of the people. Indeed, this is true of all of Halaby’s depictions of Palestine: She records alternative histories that give different accounts of what happened. Her audience, she says, are young Palestinians whom she hopes will remember their history.