Earliest Origins

Credit:

Gali Tibbon via AFP

The Nusseibeh Family: Khazraj Roots That Grew and Blossomed in Jerusalem

Snapshot

The Nusseibeh family, custodians of the keys to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre since the Muslim conquest of Jerusalem in 638, cherish their city.

The origins of Jerusalem’s Nusseibeh family trace back to the large Banu Khazraj tribe, one of the tribes of Mazin ibn al-Azd, originally from southern Arabia. Along with their cousins from the Banu Aws tribe, the Banu Khazraj supported the Prophet Muhammad and welcomed him and his Muslim followers in Medina after they fled Mecca during the hijra in 622 CE. The Banu Aws and Khazraj of Medina therefore became known as al-Ansar, or those who bring victory, for offering their homes to the first Muslims fleeing persecution.

The Nusseibehs were named after Nusseibeh bint Ka‘b of Medina, also known as Umm ‘Ammara, one of the earliest women to convert to Islam. During the Battle of Uhud near Medina in 625 CE between the early Muslims and the tribe of Quraysh, Umm ‘Ammara is said to have treated and cared for the wounded at night and fought alongside the Prophet during the day, sustaining wounds herself. The Prophet praised her: “I did not look to my right or left without seeing her fighting to defend me.”1

The detailed origins of the family are recorded by Hafiz Abdul Rahim Nusseibeh al-Khazraji in his book The Khazraj Nusseibeh Family: Custodians of History and the Present. Extensively researched and drawing on more than 830 Ottoman documents related to the family, the book traces 600 years of the family’s lineage since the advent of Islam. The sources used to tell these elaborate details also depict the family’s high social and religious status in Jerusalem, owing in large part to its members participating in the Islamic conquest of the city under the leadership of Caliph Umar in 638 CE.

The documents also reflect loyalty to the Pact of Umar (see below), whether in opening the doors of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre or protecting Christians.

Arrival in Jerusalem

Regarding the family’s arrival in Jerusalem, Hafiz Nusseibeh explains that, among the warriors in Caliph Umar’s army was Abdullah ibn Nusseibeh, the son of Umm ‘Ammara. The Umari conquest of Jerusalem, which included a four-month siege of the city, led to the capitulation of the Byzantines under Patriarch Sophronius. But upon conquering the city, Caliph Umar instructed his Muslim army to protect the churches and other non-Muslim shrines, assigning Abdullah ibn Nusseibeh the responsibility and honor of protecting the Church of the Holy Sepulchre from any attacks by Muslims or others. This was part of a treaty, known as the Pact of Umar, reached in 637 CE between the invading Muslim army and the non-Muslims of the Levant. As part of the pact, non-Muslims were granted security, protection, and rights under Muslim rule in exchange for loyalty.

The Nusseibeh family continued to inherit and execute the task of protecting the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and opening and closing its door for five centuries, until the Crusader occupation of the city in 1099, when the Nusseibehs were forcibly displaced to the village of Burin near Nablus. There, they engaged in trade and agriculture until the Ayyubid conquest in 1187, during which the Crusaders were driven out and the Nusseibehs returned to Jerusalem and resumed the duties assigned to them since Umar’s conquest.

As for the family’s more recent history in Jerusalem, Hafiz Nusseibeh draws on Ottoman documents to show that his ancestors were devoted to religious practices, including in sharia matters. For centuries, members of the family served as judges in Mamluk and then Ottoman sharia courts. In fact, the family produced a new judge about every 15 to 20 years. The Nusseibehs also served as military judges and scholars dedicated to teaching religion and serving the Dome of the Rock.

A Home Visit and a Conversation

Jerusalem Story sat down with one of the eldest members of the Nusseibeh family, 70-year-old Wajih Nusseibeh, who has been responsible for opening and closing the door of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre for more than 40 years. We met in his home in the Wadi al-Joz neighborhood of Jerusalem, in the presence of a younger family member, Munir Nusseibeh, to recount the family’s enduring presence in Jerusalem for nearly 14 centuries.

Wajih was born in 1949 in the Nusseibeh family home in the Musrara neighborhood of Jerusalem near the Damascus Gate. According to Wajih, this area was a “no-man’s-land” between 1948 and 1967, as it fell along the 1949 Green Line that divided the city.

Wajih recounted that the shells that hit the Nusseibeh home in Musrara during the 1967 War destroyed 70 percent of it, but the family was determined to restore and return to it.

Wajih described his Khazraj origins, explaining that the Nusseibeh family’s roots go back to Medina, and that their ancestor, Umm ‘Ammara, was a devoted fighter who stood by the Prophet Muhammad.

“We came to Jerusalem as conquerors during the time of Umar ibn al-Khattab, and in the early days, we lived inside the Old City. We still have several homes there to this day. The area of Bab al-Hadid, one of the gates of the al-Aqsa Mosque, was once called Haret Nusseibeh al-Khazrajiyya.”2

Special Historic Family Responsibilities

Church of the Holy Sepulchre

To this day, Wajih views the opening and closing of the door of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre as a symbolic and honorary task deeply engrained in the city’s tradition. According to Wajih, the Nusseibeh family bears specific responsibilities for this task. He explained that another of Jerusalem’s Muslim families, the Judeh family, is responsible for keeping the church keys, but they do not open the door. Instead, they hand over the keys at the opening and closing times to the person responsible from the Nusseibeh family.

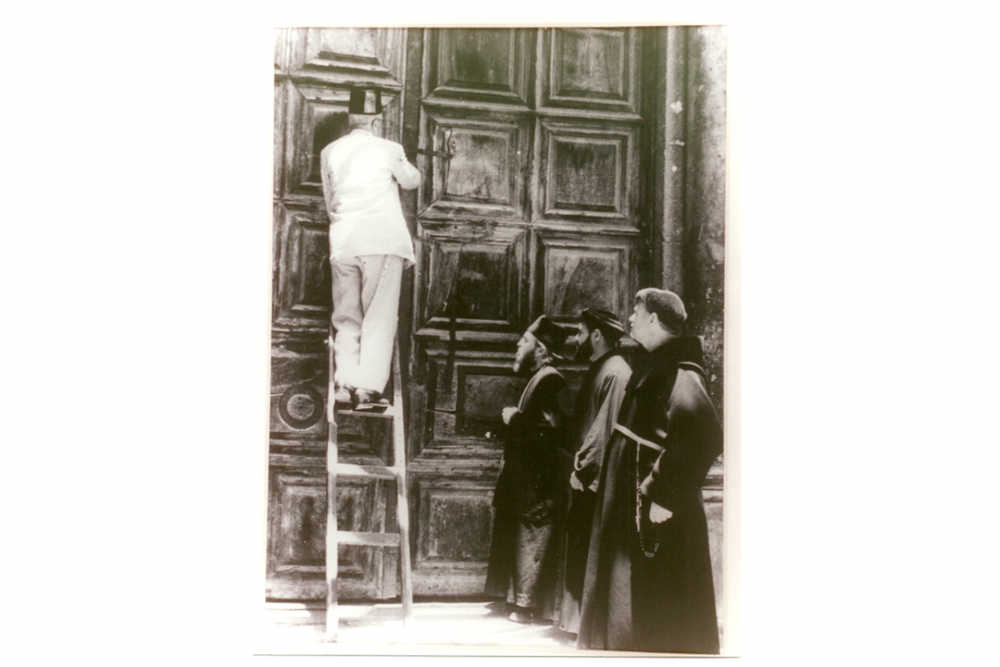

“There is a status quo arrangement in place since 1878 that ensures no single family controls the key to the church. The process begins when I knock on the church door. The sect responsible for the church at that hour hands me the ladder to climb up and open the door from the outside after a member of the Judeh family hands me the key.” To the left of the entrance to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is a stone platform for seating, designated as a resting spot for the Nusseibeh family members, who also welcome churchgoers there.

Every year during Easter, the Nusseibehs perform special rituals as part of their duties. Family members participate in a procession to visit all the patriarchates of the sects responsible for the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. After offering holiday greetings, a procession departs from the patriarchates, accompanied by the Nusseibeh family, to the church. There, the patriarch’s deputy hands the key to Wajih, who then passes it to the Judeh family.

This ritual symbolizes the Christian sects’ satisfaction with Muslims continuing to undertake the responsibility of opening and closing their church. Upon completion, on Holy Saturday (Sabt al-Nur), the Nusseibeh family enters the tomb of Jesus to ensure it is free of lanterns and candles. Subsequently, a priest enters to pour wax on the tomb, which is then sealed by the Nusseibeh family using their special seal. Afterwards, the patriarch enters to retrieve the Holy Fire from the sacred tomb, as described by Wajih.

In meticulous detail, Wajih discussed the task he has faithfully performed for four decades within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, while Munir Nusseibeh sat beside him, attentively listening to their family’s rich heritage.

Reflecting on the family’s historical role in relation to the church, Munir expressed its profound significance to him. He views this role as a testament to the family’s deep roots in the city, as well as their dedication to serving both Muslims and Christians in Jerusalem.

Munir highlighted the annual Easter rituals, which symbolize the Christian sects’ ongoing acceptance of the Nusseibeh family’s role in their church. He stated: “This is crucial because the Christian sects compete with each other for the church . . . Everyone cherishes it and strives to assert their influence. Therefore, entrusting its key to an external party holds great significance, particularly since Muslims make no claims to the church, protected as it is under the Pact of Umar and the Ayyubid conquest.”3

Al-Aqsa Mosque

Munir also pointed to his family’s historical role in serving the al-Aqsa Mosque, where they have undertaken various roles, from custodians to delivering sermons and leading prayers, as well as providing religious scholars.

The Watershed of 1967: Dispersal and Loss

Reflecting on the 1967 War, during which East Jerusalem was occupied, Wajih recounted the story of a Jordanian soldier who died defending the city in the garden of a Nusseibeh family home. He recalled discovering the deceased soldier drenched in blood. They buried him in the family home on Nablus Street in Sheikh Jarrah, placing his military helmet on the grave and adorning it with flowers before departing.

The year 1967 is not only remembered by the Nusseibeh family for the harsh days of war, but also as the pivotal year that separated 80 percent of the family members from their city, as they were living outside Jerusalem at that time.

Wajih said, “Our family has been greatly dispersed since that year, because it became impossible for them to enter the city after the [Israeli] occupation. Many of our properties in the eastern part of the city were also confiscated after the war, adding to those already seized in the western part during the 1948 War.”

Munir, an expert in international law, explained that Israel conducted a census after the war and excluded from the population registry anyone who was outside the city at the time, stripping them of their right to reside in it. Consequently, the number of the Nusseibeh family members in Jerusalem shrank significantly.

Today, no more than 20 adult males of the Nusseibeh family still reside in the city, according to Munir.

The family lost many of its properties, as vast areas of land were confiscated by the Israeli government under various pretexts, including claims of public benefit, absentee property, and abandoned property.

A City Beloved

Before leaving Wajih’s home, Munir expressed his deep attachment to Jerusalem, saying that this city is the love of his heart. He loves visiting Medina, from which his family came to Jerusalem, and is interested in reading about the history of the Khazraj tribe, but his first and last allegiance is to Jerusalem.

He concluded: “When someone asks me about my homeland, I answer that my homeland is Jerusalem, not Palestine . . . this city means everything to me, and I cannot live anywhere else.”

Wajih shared: “I hope that the Nusseibeh family can return to Jerusalem to live in our city and prepare for the establishment of our future state, Palestine. We want to live in peace and love, and do not like to see these attacks on the holy sites of Islam and Christianity. The Jews must remember that the Muslims protected them and hosted them in their lands, and it is inconceivable that the reward for this kindness is the killing of Palestinians.”

Wajih and Munir accompanied us through the orchard surrounding their home, abundant with fruit trees and various crops.

Before bidding farewell, they shared insights about the family’s gravestones, which always bear the inscription of the deceased’s name followed by the title “al-Khazraji.” This tradition reflects their ongoing effort to pass down the deeply rooted narrative to future generations of the Nusseibeh family, who maintain that their connection with the city persists against all odds.

Notes

Hafiz Abdul Rahim Nusseibeh al-Khazraji and Saqr Nusseibeh, The Khazraj Nusseibeh Family: Custodians of History and the Present [in Arabic] (Amman: Hafez Muhammad Ghaleb Hafez Nusseibeh, 2023), 25.

Wajih Nusseibeh, interview by the author, June 21, 2024. All subsequent quotes from Wajih are from this interview.

Munir Nusseibeh, interview by the author, June 21, 2024. All subsequent quotes from Munir are from this interview.